The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We would like to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. And we look at the history of unique World War Two artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

The Silent Disaster: How Communication Failures Helped Doom Operation Market Garden

As we commemorate Operation Market Garden this September, it's worth reflecting on one of the most ambitious - and ultimately ill-fated - military operations of World War II. Launched in September 1944, Operation Market Garden aimed to secure a series of nine bridges in the Netherlands, potentially paving the way for a swift advance into Germany. It was a massive undertaking, involving over 34,000 airborne troops and 50,000 ground forces. Yet, what began with high hopes ended in a costly failure, partly because of a communications breakdown.

Operation Market Garden: 17 to 25 September 1944

As we commemorate Operation Market Garden this September, it's worth reflecting on one of the most ambitious - and ultimately ill-fated - military operations of World War II. Launched in September 1944, Operation Market Garden aimed to secure a series of nine bridges in the Netherlands, potentially paving the way for a swift advance into Germany. It was a massive undertaking, involving over 34,000 airborne troops and 50,000 ground forces. Yet, what began with high hopes ended in a costly failure, partly because of a communications breakdown.

At the heart of Market Garden's communication crisis was the inadequacy of the radio equipment. The British Army's standard radio set, the Wireless Set No. 22, proved insufficient for the task at hand. These radios had a maximum range of around six miles under ideal conditions, yet the Corps Headquarters was positioned a distant 15 miles away. To compound matters, the terrain around Arnhem presented additional challenges that the planners had failed to fully account for. The Arnhem area was characterised by woodland and urban buildings. These physical obstacles severely interfered with radio transmissions, further diminishing the already limited range of the No.22 sets. As a result, what should have been a vital lifeline for the paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division fighting desperately to hold the north side of the bridge at Arnhem became a silent witness to their isolation and eventual defeat.

Interestingly, a potential solution to these communication problems was literally at hand. The Netherlands boasted an extensive and sophisticated telephone network, largely intact despite years of German occupation. This network was remarkably resilient, comprising three interconnected systems: the national Ryks Telefoon system, the Gelderland Provincial Electricity Board's private network, and a clandestine network operated by Resistance technicians. Even when key exchanges were disrupted, the Dutch were still able to communicate using alternative routings.

Yet, astonishingly, Allied planners failed to fully leverage this resource. This oversight raises profound questions about the rigidity of military thinking. Why did the Allied command, known for its adaptability in other areas, fail to pivot to this seemingly obvious solution? The answer likely lies in a combination of factors: overconfidence in existing systems, security concerns, lack of familiarity with local infrastructure, the fast-paced nature of the operation, and a wariness of the Dutch Resistance.

British XXX Corps cross the road bridge at Nijmegen

The consequences of this failure were dire. While some units made limited use of the phone system, the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem - where the need was most critical - did not. They made no attempt to convey their urgent need for supplies or relief via the phone system to the corps headquarters. Ironically, Dutch agents inside the 82nd Airborne's landing area used the phone system early on D+1 to inform the 82nd that “the Germans are winning over the British at Arnhem” - the first indication that the 1st Airborne was in serious trouble.

In the face of radio failures, the Allied forces resorted to various other communication methods, each with its own limitations. Carrier pigeons proved unreliable, with many birds failing to deliver messages. Traditional forms of communication like land lines, runners, and dispatch riders were vulnerable to enemy fire and the chaos of battle. The artillery net ended up being one of the more reliable communication methods, allowing for effective artillery support and occasional relay of messages to higher command.

The communication failures during Operation Market Garden offer valuable insights into military organisational thinking. They underscore the importance of flexibility, the need to understand and potentially leverage local infrastructure, the crucial role of contingency planning, and the necessity of fostering a culture that encourages quick problem-solving and innovative thinking at all levels of command.

It's worth noting the contrast between the German military's mission-type tactics (Auftragstaktik), which emphasized flexibility and initiative, and the British Army's reliance on detailed orders and strict adherence to commands. This difference in command styles meant that German forces could often exploit opportunities more rapidly, while British forces maintained tighter control but at the cost of agility.

As we reflect on the events of eighty years ago, it's clear that the lessons learned extend far beyond the realm of military strategy. In any high-stakes endeavour, the ability to communicate effectively - and to adapt when primary methods fail - can mean the difference between success and catastrophic failure. The underutilisation of the Dutch phone system stands as a poignant example of how overlooking available resources can have far-reaching consequences.

The story of Operation Market Garden serves as a stark reminder of the critical role that effective communication plays not just in military operations, but in any complex undertaking. It's a lesson that remains relevant today, in fields ranging from business to disaster response. As we face our own challenges in an increasingly connected world, let's not forget the silent disaster that unfolded in Holland eighty years ago - and the valuable lessons it still has to teach us.

References

1. Middlebrook, M. (1994). Arnhem 1944: The Airborne Battle. Westview Press.

2. Ryan, C. (1974). A Bridge Too Far. Simon & Schuster.

3. Kershaw, R. (1990). It Never Snows in September: The German View of Market-Garden and the Battle of Arnhem, September 1944. Ian Allan Publishing.

4. Buckley, J. (2013). Monty's Men: The British Army and the Liberation of Europe. Yale University Press.

5. Beevor, A. (2018). The Battle of Arnhem: The Deadliest Airborne Operation of World War II. Viking.

6. Powell, G. (1992). The Devil's Birthday: The Bridges to Arnhem 1944. Leo Cooper.

7. Badsey, S. (1993). Arnhem 1944: Operation Market Garden. Osprey Publishing.

8. Hastings, M. (2004). Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 1944-1945. Alfred A. Knopf.

9. Zaloga, S. J. (2014). Operation Market-Garden 1944 (1): The American Airborne Missions. Osprey Publishing.

10. Clark, L. (2008). Arnhem: Operation Market Garden, September 1944. Sutton Publishing.

11. MacDonald, C. B. (1963). The Siegfried Line Campaign. Center of Military History, United States Army.

12. Bennett, D. (2007). Airborne Communications in Market Garden, September 1944. Canadian Military History, 16(1), 41-42.

13. Greenacre, J. W. (2004). Assessing the Reasons for Failure: 1st British Airborne Division Signal Communications during Operation 'Market Garden'. Defence Studies, 4(3), 283-308. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1470243042000344777#d1e290

The British Army’s Occupation of Northwest Germany after May 1945

In this article, we will focus on the British occupation of Germany after May 1945, the British Army's occupation of West Berlin, the Victory Parade of July 1945, and relations with the Soviets.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945, the victorious Allied powers divided the country into four occupation zones, each controlled by one of the four occupying powers - the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. This division of Germany would mark the beginning of a new era for the country, as it faced a long and difficult process of reconstruction and democratization. In this article, we will focus on the British occupation of Germany after May 1945, the British Army's occupation of West Berlin, the Victory Parade of July 1945, and relations with the Soviets.

The British Occupation of Germany after May 1945

On 25 August 1945, Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group was renamed the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). It was responsible for the occupation and administration of the British Zone in northwest Germany, including the cities of Hamburg and Bremen, assisted by the Control Commission Germany (CCG). The CCG took over aspects of local government, policing, housing and transport.

Their primary objective was to demilitarize and disarm the defeated German forces, as well as to dismantle the Nazi regime and bring war criminals to justice. The British forces, under the command of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, faced a daunting task, as Germany was in a state of complete chaos and disarray.

One of the first challenges the British faced was dealing with the large numbers of displaced persons, refugees, and prisoners of war. The British Army, along with other Allied powers, established numerous displaced persons camps and worked to repatriate prisoners of war and refugees to their home countries. The British also faced the challenge of providing food and shelter to the German population, which was suffering from severe shortages of basic necessities such as food, fuel, and medicine. The BAOR mobilised former enemy soldiers into the German Civil Labour Organisation (GCLO), providing paid work and accommodation for over 50,000 Germans by late 1947.

The BAOR was also responsible for pursuing suspected war criminals in its zone of occupation. It established the British Army War Crimes Investigation Teams (WCIT) and was assisted by other units, including the Special Air Service (SAS). The most famous Nazi caught by the British was Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and one of the main architects of the Holocaust. He was arrested at a checkpoint and taken to an interrogation camp near Lüneburg. However, Himmler was able to escape prosecution for his crimes by committing suicide with a concealed cyanide pill. Political support for war crimes prosecutions soon declined as relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated. It soon became a political necessity for the Western powers to make friends with the Germans rather than prosecute them.

The British Sector of Berlin 1945

The British Army's occupation of the British sector of Berlin in 1945 was a key moment in the post-war history of Germany. Berlin, which was located deep within the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, was divided into four sectors, with the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain, and France each controlling a sector. The British sector was in the western part of the city.

The British Army faced numerous challenges in the occupation of Berlin. The city had been heavily bombed during the war, and many buildings were in ruins. The British Army worked to rebuild the city's infrastructure and provide basic services such as water, electricity, and sanitation.

Another major challenge faced by the British Army was dealing with the Soviet Red Army, which was stationed in and around Berlin. The relationship between the British and the Soviets was strained, with tensions running high over issues such as the repatriation of Soviet prisoners of war and the control of Berlin. The British Army, along with the other Allied powers, worked to maintain a delicate balance of power in the city, while also providing security and maintaining order.

The Victory Parade of July 1945

On 21 July 1945, the British held a victory parade through the ruins of Berlin to commemorate and celebrate the end of the Second World War. Around 10,000 troops of the British 7th Armoured Division, the famous 'Desert Rats', were paraded under review by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. On 7 September 1945, there was another parade featuring all the victorious Allies, but neither Montgomery nor U.S. General Dwight D Eisenhower attended. This gesture signified a deterioration in the relationship between the Allies, as differences in ideology between the West and the Soviet Union were becoming harder to ignore and the slide towards a Cold War had begun.

British Pathe News footage of the Berlin Victory Parade, 21 July 1945.

An Iron Curtain

Relations between the Western powers and the Soviet Union deteriorated immediately following the end of the war in Europe. The main sources of tension were the Soviet Union's unwillingness to allow democratic governments to emerge in Eastern Europe, and its desire to maintain a sphere of influence in the region. The Western powers, led by the United States, saw this as a threat to their own security and interests.

The Soviet Union's aggressive actions in the post-war period, including the establishment of communist governments in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, fuelled Western fears of Soviet expansionism. The United States responded by implementing the Truman Doctrine, which committed the U.S. to support countries threatened by communism, and by providing economic and military aid to Western Europe through the Marshall Plan.

Tensions between the West and the Soviet Union reached a boiling point in 1947 when the Soviet Union refused to participate in the Marshall Plan and instead formed its own economic bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). In 1948, the Soviet Union blockaded Berlin, prompting the Western powers to launch the Berlin Airlift to supply the city.

On March 5, 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "Iron Curtain" speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. In this speech, Churchill warned of the growing Soviet threat in Europe and called for a closer alliance between the United States and Great Britain to contain Soviet aggression. The speech marked a turning point in the post-war era and is considered a seminal moment in the Cold War.

In 1949, the three western occupation zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Soviets followed suit in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). In 1955, West Germany joined NATO and was encouraged to build a new military, the Bundeswehr. In response, the Communist states of Eastern Europe formed the Warsaw Pact.

Sources:

Photography/Images:

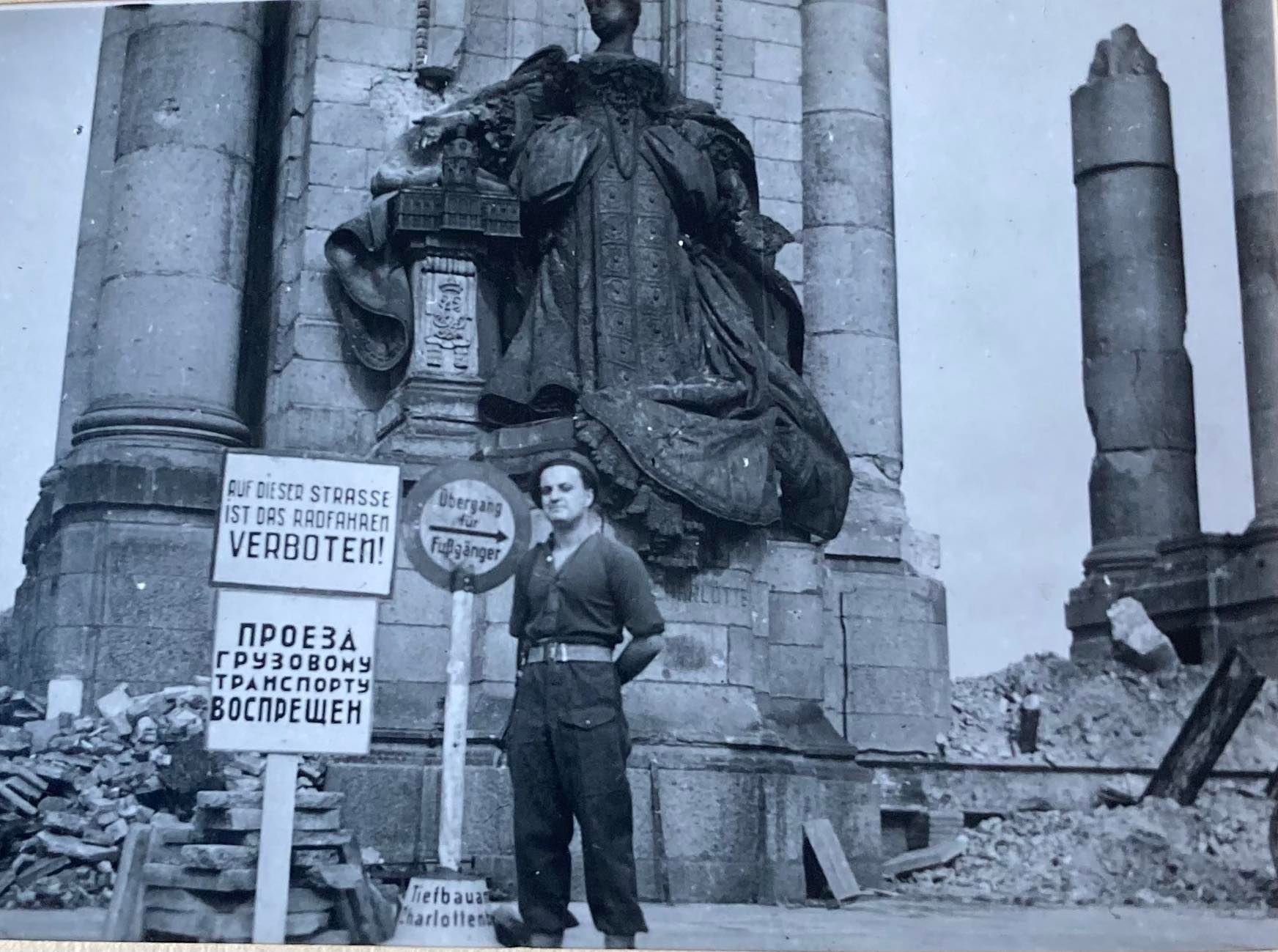

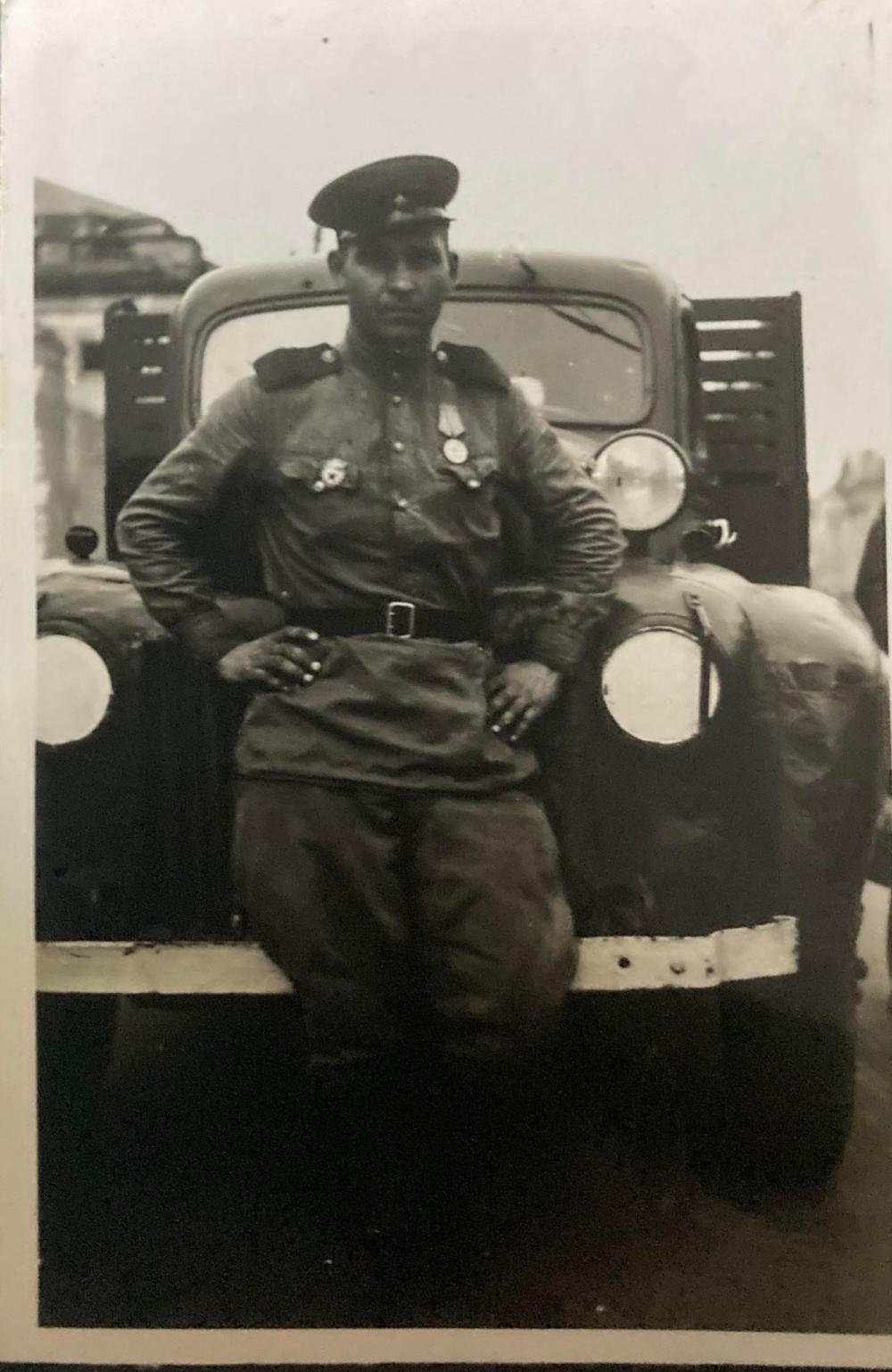

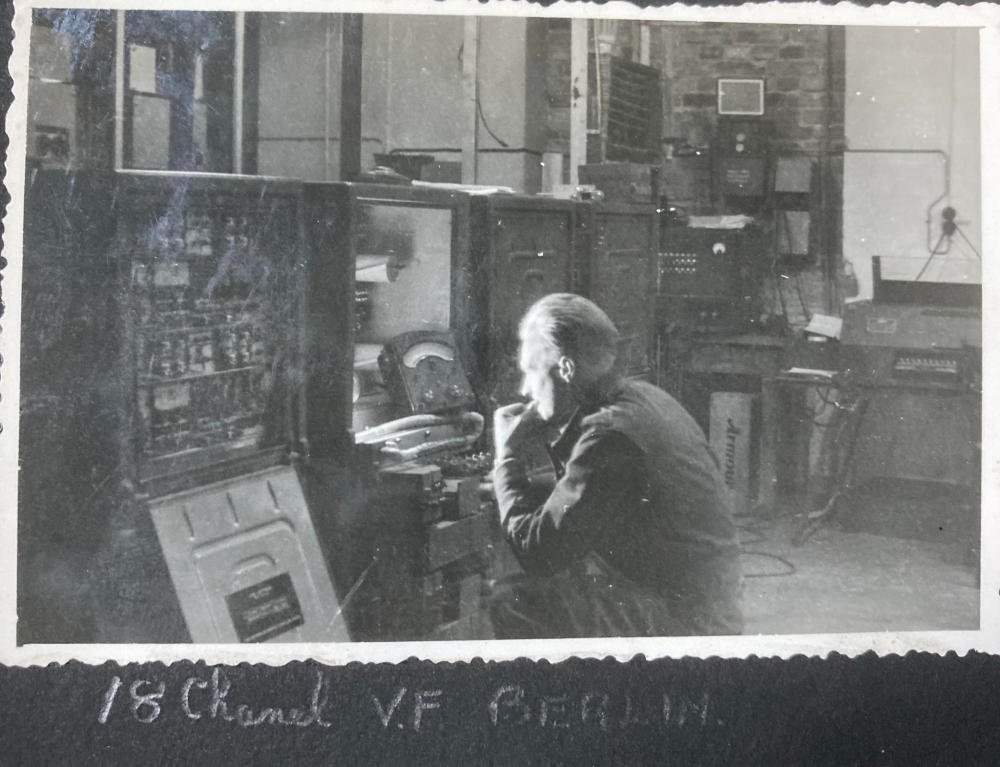

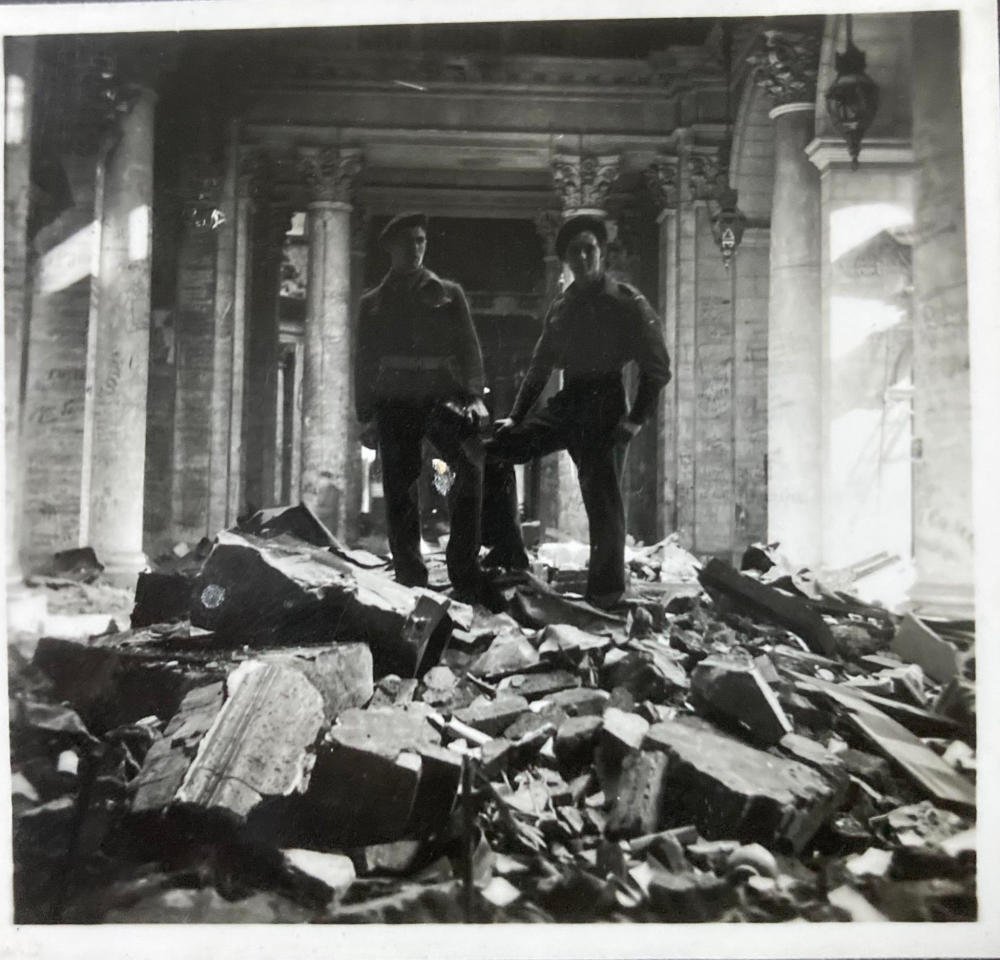

All photographs used to illustrate this article were taken by my relative George Trumpess who was stationed in Minden, Germany, and travelled regularly to Berlin during the summer of 1945.

George's War: From Harpenden to Berlin with No. 1 Special Wireless Group

In this blog post, we examine the wartime service of George Trumpess, who was a member of No. 1 Special Wireless Group, Royal Signals. During the Second World War, 40 Special Wireless Sections were engaged in enemy radio traffic intercepts for the Army (Y Service). George would serve throughout the Campaign for Northwest Europe, and travel from sleepy Hertfordshire to the ruins of Berlin in 1945.

George Trumpess, left, at Brandenburg Gate, Berlin, 1945

Recently, a relative of mine had the unenviable task of having to clear the contents of his late parent’s house. Among the countless objects accumulated over a lifetime emerged a large, handcrafted wooden box and several photograph albums. The box contained an assortment of Second World War German medals and coins. The photograph albums revealed a tantalising glimpse into George Trumpess’s wartime service with the Royal Signals. George had been very circumspect about his military career.

George’s collection of Second World War German medals, Nazi currency, assorted photos, and his own campaign medals

Initially, I started my research into George’s unit by contacting the Royal Signals Association on the social media platform Facebook. One member of the Facebook group recommended I contact Bletchley Park. Officially, the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), Bletchley Park was a top-secret centre of Allied codebreaking during the war also known as Station X. Dr Thomas Cheetham, Research Officer at Bletchley was able to provide the following:

George was a member of No. 1 Special Wireless Group (1 SWG), who would become 1 Special Wireless Regiment (1 SWR) in late 1945. 1 Special Wireless Group comprised of army signals units intercepting, decrypting, and analysing low-grade German Army radio traffic and cyphers in the field. It operated in Northwest Europe from D-Day onwards.1

George in the ruins of the Reich Chancellery, Berlin, 1945

Dr Cheetham was not able to provide any information on the Regiment’s post-war activities. However, it appears that 1 SWR was collecting signals intelligence (SIGINT) on the Soviets immediately after the war, although they were still our allies at the time.

Dr Cheetham recommended that I contact the Military Intelligence Museum, which I did. Alan Judge, Corps Historian, Military Intelligence Museum responded with the following:

Not a lot is known about this unit. It started as 1 Wireless Intelligence Company (WIC) of No. 1 Special Wireless Group, which formed up in November 1945 with a strength of 18 officers and 90 other ranks. Both these units were in Gneisenau Kaserne in Minden. 1 WIC's role was signals intelligence, they listened, initially, for clandestine radio transmissions from the remnants of the Nazi resistance units until it became obvious that Nazi resistance was no longer a threat.

However, the threat from the Soviet Union was then becoming more apparent and the unit started to pay more attention to the USSR and the countries under its domination. By 1949, 1 Wireless Group had been re-designated 1 Wireless Regiment and moved to Nelson Barracks in Münster. Detachments were in Berlin at RAF Gatow, Efeld, Cuxhaven, Iserlohn, and Plön in Schleswig-Holstein. In 1970 it was renamed 13 Signal Regiment, which moved into Mercury Barracks near Birgelen on the Dutch/German border in 1955. The unit had a strong Intelligence Corps representation as well as around 80 Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC) personnel. There followed a series of moves until 1994 when 13 Signal Regiment closed for good.2

Formation of 1 SWG

No. 2 Company, GHQ Signals went to France with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in 1940.3 In July, following the evacuation of the BEF from Dunkirk, the unit was renamed No. 1 Special Wireless Group. The unit was based at Rothamsted Manor, Harpenden under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel A.E. Barton.4 1 SWG remained at Harpenden until 22 June 1944, when they closed down Rothamsted Manor and moved in three shifts (A, B and C) of eight detachments to Normandy.5

During the Second World War, 40 Special Wireless Sections were engaged in enemy radio traffic intercepts for the Army (Y Service). Each Section was a composite of Royal Signals operators, Military Intelligence, often with linguistics skills, and Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) providing drivers and logistical support. The parent organisation was the Wireless Group, which trained Signals operators, held stores of equipment and spares, and ran training courses for Intelligence officers and NCOs on Signals sections.6

Recruitment & Training of Special Operators

The recruitment of Y Service operators required the candidates to pass an IQ test, demonstrate an ability to work under pressure, and have the patience to wait for hours until an enemy radio station started broadcasting. Candidates had to show that they were mature enough not to gossip about their work. They also had to be mentally and physically resilient, often working long hours with little sleep and irregular meals. Forces operators’ training lasted 19 weeks, which included both basic military and technical training.7

Basic training for wireless operators consisted of 6-hours of military training and 2-hours of technical training per day. After an aptitude test, those selected for further training were sent to the Special Operations Training Battalion (SOTB), situated in Douglas, Isle of Man, from 1942.8

In his memoir, Major G.K. Rothwell, 1 Special Wireless Group, described his extensive training:

The initial training was standardised for all arms and comprised six weeks of rigorous and exhausting infantry training. The training day ran from 07.30 to 18.00 including Saturdays. It was only after four weeks, when we were fitted with Battle Dress, that we were allowed out on a Sunday afternoon to go to the Club at Camp Centre.

After leave I was instructed to proceed to the Isle of Man where the Special Operator Training Battalion was located. A long row of Boarding House along the promenade had been requisitioned and the promenade divided in half by a wire mesh fence. Special Operators were trained to receive and send Morse to British Army standards and additionally learnt the styles, codes, and procedures of German and Italian services.

After three months or so there was a test which eliminated the less proficient. The remainder continued the course until they qualified as Operator Special Class II after six months or so. Training continued with operational training, meaning one practised monitoring actual German networks. Additionally, Japanese procedures were taught as the Japanese Morse alphabet had 72 characters this was not at all simple.

So, the training lasted over a year (extraordinary for the wartime), and it was not until April 1944 that I was to join No. 1 Special Wireless Group, then located in a large country house at Rothampsted in Harpenden.9

1 SWG & Campaign for Northwest Europe

The long-awaited Second Front finally opened with the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944. On the morning of D-Day, the mobile section (MobSec) of 1 SWG identified 21st Panzer Division moving from Falaise toward Ouistreham (Sword Beach). As a result, the Division was subjected to an Allied air attack. Next, having found the road bridge over the Caen Canal (Pegasus Bridge) in the hands of British 6th Airborne, 21st Panzer had to detour via Caen, which delayed their planned counterattack until 16.30hrs. When they finally attacked, 21st Panzer lost approximately 50 tanks from a strength of 127. Nevertheless, they did frustrate General Montgomery’s planned objective of taking the city of Caen on D-Day.10

From the 14 June, MobSec, 1 SWG started to waterproof their vehicles in anticipation of crossing to Normandy. However, they were then ordered to de-waterproof them at the end of July. Finally, on 8 August the unit received its movement orders, and arrived in Normandy on 10 August 1944.11

Operation OVERLORD, the Battle for Normandy, raged on for three months. The Germans finally withdrew across the river Seine at the end of August 1944. After weeks of inching forward in the notoriously closed country of the Normandy bocage, the Allies suddenly made spectacular advances into France and Belgium.

In August 1944, Major Rothwell, 110 SWS, was monitoring German radio traffic in the Falaise Pocket:

The Germans were using a three letter Book Code. A Book Code provides little or no protection if the enemy has a copy of it. Now we did have a copy of the code book! So, when I began picking up a long message in this code, the Intelligence chap was sitting on the back steps of the radio van decoding it as I handed him each sheet as it was completed. And it turned out to be the complete plan for the counterattack the Germans planned at Mortain.12

On 1 September 1944, one detachment of the 110 Special Wireless Section (110 SWS) was attached to the Guards Armoured Division. The remainder of 110 SWS was attached to XXX Corps HQ, following in the wake of the Guards as they advanced across Belgium. On 3 September, Guards Armoured liberated the Belgium capital of Brussels. Corporal Harold Everett, 110 SWS, recalled the liberation and subsequent celebrations:

The noise, the ecstasy of the crowd, the knowledge that we, the British, were the cause of this great outburst of joy and gratitude gave us feelings of pride and pleasure that it is impossible to put into words. I felt emotionally super charged. On that September day I lived a moment in history that I can never live again.13

Between 5 and 9 September 1944, Shift B of 1 SWG moved six officers, 174 other ranks and 43 vehicles to a transit camp in Wickham, Hampshire. Next, they embarked on Landing Ship, Tank (LST) 158 sailing from Gosport and landed at Arromanches, Normandy. Similarly, Shift C landed in France on 15 September 1944. 1 SWG then moved from Amiens to Brussels, Belgium.14

On 14 September, 1 SWG and 1 Special Intelligence Company (1 SI Coy) moved to Brussels to set up an important intercept station.15 According to Hugh Skillen, Ultra and Y Section intelligence indicated a rapid build-up of German forces in the Arnhem-Nijmegen area at least one week before the start of the ill-fated Operation MARKET-GARDEN.16

Detachments of 1 SWG were operating in Eindhoven, Holland during Operation MARKET-GARDEN (17 to 25 September 1944) but the unit’s war diary makes no mention of it.17 At the end of September MobSec, 1 SWG was attached to the American 12th Army Group.18

During November, No. 7 SW Section (Type A: Army HQ), 109 and 110 SW Sections (Type B: Corps HQ) arrived in the Brussels area. According to the war diary, the winter passed without Christmas, the New Year or Operation VERITABLE. The same phrase is repeatedly used in the war diary: Nothing of importance to record. Presumably, the lack of information recorded in the war diary at a group level is a security precaution in case the documents were ever captured.19

On 13 December 1944, the war diary for MobSec, 1 SWG mentions a force of 20 Germans 3-miles from their positions, and the men having to stand to until the morning. On the 16 December, the war diary records a breakthrough of German forces North of their position at Chattancourt close to the Meuse River. This attack was the Ardennes Counteroffensive, the last major German offensive of the war, also referred to as the Battle of the Bulge. During the night and early morning of the 23/24 December, the war diary records enemy air activity and some bombing nearby but no casualties.20

In February 1945, following leave in the UK, Major Rothwell returned to Holland and Operation VERITABLE (the clearing of German forces from the West bank of the Rhine):

I returned to the section at Issum in Holland, where the Reichwald Forest was slowly being cleared in some very bitter fighting and preparations were being made for the crossing the Rhine. Shift working was back, with a continuous system without free days. The shifts were worked so: 08.00 –13.00, 22.00 – 03.00, 13.00 – 17.00, 03.00 – and then 17.00 – 22.00 before starting round again.

And when one was not on a radio set, sleeping, meals washing (self & cloths) weapon cleaning, sentry duty and various other chores had all to be fitted in. And whenever we moved the old latrine pit had to be filled in and new slit trenches dug at the new site!21

During the winter months of 1945, 110 SWS repeatedly moved locations, setting up new stations, transmitters, and continually changed cypher books. At the same time, leave was organised in the UK and Paris. On 8 May 1945, the war diary for 110 SWS simply states that hostilities officially declared closed.22 The war in Europe was over for 1 SWG.

Visit George’s War in our Gallery section to see 46 photographs of George and his comrades in Berlin between 1945 and 1946. Click Here.

Victory in Europe & Russian Intercepts

By mid-April 1945, 1 SWG was located at Kempen, Germany, northwest of Dusseldorf. By June, the unit had moved to Minden, between Munster and Hanover. The War Diaries are silent about German capitulation in May 1945. Throughout the summer, 1 SWG remained busy and had numerous visitors from Signals Research and Development Establishment (SRDE) and Southeast Asia Command (SEAC). Of course, Japan would not be defeated until August 1945, and it was certain that some elements of Y Service would have been redeployed to the Pacific if the war had continued. In mid-July, the unit found time to exhibit captured German cypher equipment, visited by Chief Signals Officer, 21st Army Group. At the same time, some sections were being returned to the UK and demobilised.23

It seems that 1 SWG was intercepting Russian wireless and possibly landline traffic after May 1945. On 14 September 1945, GC&CS and Foreign Office prepared a draft policy paper on what radio traffic should be monitored in the immediate post-war period. Russia was a prime target for intelligence gathering. The paper stated:

The Russians are realists, and they will intercept our traffic and expect us to intercept theirs.

The paper continued:

Interception of Russian traffic is normally difficult for us, but owing to their present advance westwards, the opportunity to do so is good and an intense study could be made while there is a chance and resources available.24

As the Cold War got underway, GC&CS moved from Bletchley Park to Cheltenham in 1952, having changed its name to Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in 1946.

References:

Dr Thomas Cheetham, Research Officer, Bletchley Park, museum & heritage attraction, https://bletchleypark.org.uk/, 2020.

Alan Judge, Corps Historian, Military Intelligence Museum, https://www.militaryintelligencemuseum.org/, 2020.

Hugh Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves: A History of Y Sections during the Second World War (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1989), p. 56.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, p. 110.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, p. 397.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, pp. 50-51.

Sinclair McKay, The Secret Listeners: The Men and Women Posted across the World to Intercept the German Codes for Bletchley Park (London: Aurum Press Ltd, 2013), pp. 6-7.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, pp. 50-51.

The Y Service 1939-1945, Major G.K. Rothwell (Ret'd), extract from his biography, from March 1943 to June 1945, https://www.goldbeach.org.uk/yservice/Rothwell.htm, downloadable PDF, 2021.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, pp. 397-398.

The National Archives (TNA), WO 171/2042, Mob Sect, No. 1 Special Wireless Group, June to August 1944.

Rothwell, The Y Service 1939-1945.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, pp. 432-433.

TNA, WO 171/2041, War Diary, No. 1 S.W. Group, R. Signals, 5 to 9 September 1944.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, p. 431.

Skillen, Spies of the Airwaves, pp. 441.

TNA, WO 171/2041, War Diary, No. 1 S.W. Group, September 1944.

TNA, WO 171/2042, War Diary, Mob Sect, September 1944.

TNA, WO 171/2041, War Diary, No. 1 S.W. Group, September 1944 to November 1945.

TNA, WO 171/2042, War Diary, Mob Sect, December 1944.

Rothwell, The Y Service 1939-1945.

TNA, WO 171/6051, War Diary, 110 S.W. Section, 1 January to 30 June 1945.

TNA, WO 171/2041, War Diary, No. 1 S.W. Group, April to September 1945.

Kenneth Macksey, The Searchers: Radio Intercept in Two World Wars (London: Cassell Military Paperbacks, 2003, (reprinted 2018), p. 274.

Additional resources:

Birgelen Veterans Association

BOAR Locations, Mercury Barracks: https://www.baor-locations.org/MercuryBks.aspx.html

Royal Signals, Corps History: https://www.royalsignalsmuseum.co.uk/