The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We would like to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. And we look at the history of unique World War Two artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial

In this blog post, we visit the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial. The Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial holds the graves of 3, 812 soldiers, sailors and airmen. Another 5, 127 souls are commemorated on the Tablets to the Missing. During a recent visit to the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial I came across the headstones of three members of the US 29th Infantry Division, and decided to investigate.

Known as the “Friendly Invasion”, 1.6 million American service personnel were stationed in the UK by 6 June 1944. Three months after D-Day, 1.2 million of those Americans had been committed to battle. Of course, Americans had been supporting Britain from the very start of the Second World War from the famous Eagle Squadrons to US Navy and Merchant Marine. The US Eighth Airforce bombed targets across Occupied Europe and Germany from August 1942 to May 1945. By the end of the conflict, over 3 million Americans had been sent to Britain. Regrettably, many ground, naval and air force personnel would never return home.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 American military cemeteries and 29 monuments across 16 countries. There are two American military cemeteries in the UK, situated in Cambridge and Surrey. The Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial hold the graves of 3, 812 soldiers, sailors and airmen. Another 5, 127 souls are commemorated on the Tablets to the Missing.

During a recent visit to the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial, I came across three members of the US 29th Infantry Division. As an associate member of the 29th Division Association, I took photos of each headstone so that I could do a little research about these men. In the case of PFC. Henry R. Dority, Jr, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, it seems likely that he was killed in a training accident or succumbed to some sort of illness. The 116th Infantry Regiment had started amphibious assault training on the English coast by the date of this death, December 26th, 1943.

Henry R. Dority, Jr

YOB: 1920

Home: Halifax, VA

Occupation: Semi-Skilled Painter, Construction or Maintenance

Marital Status: Single with dependents

Enlisted: 3 February 1941

Service No: 20364712

Private First Class, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division

DOD: 26 December 1943

Private Billie Wilson must have been badly wounded during the initial bitter fighting for the beachhead following the D-Day landings. Billie’s unit, Company L, 3rd Battalion, 175th Infantry, landed on Omaha Beach, Normandy, on 7 June 1944, D+1. Their landing was opposed. On 8 June, the 1st battalion passed through and captured La Cambe. However, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were strafed by RAF Typhoon fighter-bombers with six men killed and 16 wounded. It is possible that Billie was wounded during the blue-on-blue attack by Allied planes. There was some opposition at the start of the push into Isigny. The operation did not start until dusk. Once again, it is possible that Billie was wounded and reported missing during the night advance on Isigny. The 3rd Battalion supported by tanks took Isigny only to find it abandoned by the Germans and set on fire by Allied bombing. We do know that Billie was seriously wounded, returned to the UK and subsequently died of his wounds on 12 June 1944. On 9 June, 175th pushed through Isigny and supported by tanks secured a bridge over the Vire River. The regiment then consolidated around Lison on the 9 and 10 June 1944.

Billie Wilson

YOB: 1923

Home: Kentucky

Occupation: General Farmer

Marital Status: Single

Enlisted: 1 June 1942

Service No: 15114820

Private, Company L, 3rd Battalion, 175th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division

Reported missing in action on 8 June; dropped rolls on 21 June

DOD: 12 June 1944

Awards: Purple Heart

Frank J. Lapkiewicz joined Company E, 115th Infantry Regiment on 4 September from the replacement depot as a Rifleman. On 16 September, Frank was listed as lightly injured in action (LIA) and moved to the hospital. In November 1944, the 29th Infantry Division began its drive to the Roer River, Germany, blasting its way through Siersdorf, Setterich, Durboslar, and Bettendorf, and reaching the Roer by the end of the month. Frank returned to duty on 14 November. The attack on Durboslar, preceded by an artillery barrage, started on 19 November. The 2nd Battalion, 115th Infantry advanced on the town supported by tanks and artillery. In response, the Germans brought up 12 self-propelled 88mm guns. Two Allied airstrikes helped to dislodge the German defenders. Small unit actions continued into the night and the 115th took a number of prisoners. At some point during the fighting on the 19, after just five days back in the line, Frank was seriously wounded. Frank was evacuated back to the UK but died of his wounds on 6 December 1944.

Frank J. Lapkiewicz

YOB: 1915

Home: 1111 Maple Street, Wilmington, Delaware

Parents: Leon & Nellie Lukiewska

Occupation: Skilled worker in manufacturing

Marital Status: Single

Enlisted: 28 February 1944

Service No: 42085191

Private, Company E, 2nd Battalion, 115th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division

Wounded during the battle for the German town of Durboslar

DOD: 6 December 1944 (Died of Wounds)

Awards: Purple Heart

In total, the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial contain the graves of around 45 members of the 29th Division’s three infantry regiments. The American Battle Monuments Commission keeps the cemetery in immaculate condition. The visitors centre and helpful staff ensure that the stories of service personnel such as Henry, Billie and Frank are preserved and their sacrifices remembered.

Donald A. McCarthy, A Veteran’s Story

In this post, we tell the story of D-Day veteran Donald A. McCarthy, who served with Headquarters Company, First Battalion, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division, and landed on Omaha Beach.

In 1999, I was researching the D-Day landings for a radio project. As part of my research, I was lucky enough to start corresponding with 29er veteran, Donald A. McCarthy. Sadly, Donald passed away in 2017 at the grand age of 93. He lived a full and active life. He was rightly proud of his military service. He was Commander of the 29th Division Association from 1995-96 and made 14 trips back to the Normandy beaches and battlefields. In 2014, he was awarded the French Foreign Legion of Honour. As part of the 75th anniversary of D-Day and battle for Normandy, I thought it worth sharing Donald’s own experience of landing on Omaha Beach as he told it to me.

Training for D-Day

I was a member of Headquarters Company, First Battalion, 116th Infantry, 29th Division. I was drafted in July 1943 after graduating from High School. I completed basic infantry training in Alabama, shipped overseas on the Il de France, assigned to 1BN 116t RCT at Ivybridge, 26 January 1944. The RCT (Regimental Combat Team) began intensive training at the Assault Training Centre, Woolacombe Beach on the North West Coast of Devon, and later in April participated in Exercise Fox at Slapton Sands. We were fortunate to have preceded the horrible debacle of Exercise Tiger of 27th April.

Omaha Beach

Again, I was fortunate to have survived the landings of the third wave at Omaha Beach. Although the flotilla was originally scheduled for Dog Green sector of the beach, the British Coxswain and the entire flotilla of LCAs (Landing Craft Assault) from the SS Empire Javelin (Infantry Landing Ship, Large) were carried in an easterly direction by the tide toward the Dog Red sector and the Moulin Draw.

My LCA had taken on water, was swamped and sank about 200 yards from the low watermark and beach obstacles. Several of us swam in behind bodies and attempted to hide behind the obstacles from machine gun and artillery fire. Although the MG fire was intense, the Germans on the bluff were unable to see us because of smoke from burning grass and buildings blowing east from the Vierville (Vierville-sur-Mer) area. The smoke screen provided an opportunity to run from the water’s edge, and the fear of getting run down from incoming landing craft, and find protection from the high water shingle.

Evacuation

Some of us managed to crawl toward the Vierville Draw and were eventually able to move up the draw and reach our objective, the church in Vierville. We came under fire from our own navy and I was ordered to return to the beach and attempt to contact the US Navy beach master. I was hit by an overhead shell burst in my left leg after finding a radio. The radio caught the brunt of the burst and both my leg and the radio became inoperative. A medic dragged me to a makeshift slit trench near the shingle within 100 yards of the draw. The following morning hundreds of us managed to walk towards the Moulin Draw and most were evacuated on LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) back to ports in Britain. Some of us recovered and returned to Normandy within three weeks.

Wounded Again

I was able to re-join my company by early July and participate in the battle for St. Lo and Vire. During the attack at Vire, I came under heavy fire in an abandoned garage. The roof collapsed and debris hit my hand and neck. I did not consider my wounds serious until a form of blood poisoning finished my days with the 116th in France.

After several weeks in a General Hospital at Great Malvern, I was assigned to an Infantry Training Centre at Tidworth Barracks. We ran a training facility for Air Force personnel and shipped them to Holland and Germany as infantrymen.

Home

I remained a PFC (Private First Class) throughout my time in the ETO (European Theatre of Operations). In January 1946, I returned home to Boston and enrolled in college. I got married and worked for Bell Systems for 30 years. My work with Bell Systems centred on defence telecommunications with the US Navy including a period in Vietnam between 1967 and 1968. After leaving Bell, I worked for the Chamber of Commerce in Providence, Rhode Island. In 1969, I returned to England, chartered a small sailboat at Gosport, and sailed to Omaha Beach to recapture the event that changed my life. Since then I have returned to Normandy to take part in D-Day anniversary events with many other 29ers.

-END-

Visit the 29th Division Association website to learn more about the unit’s contribution during World War Two. Additional material courtesy of US Department of Veteran Affairs and Back to Normandy website.

D-Day 75th Anniversary Commemoration

As part of the D-Day 75th-anniversary commemorations, The War Years will be adding a range of content over the coming week.

As part of the D-Day 75th-anniversary commemorations, The War Years will be adding a range of content over the coming week.

The Story of D-Day, Part One

The Plan

The largest amphibious operation in military history, code-named Overlord, D-Day started in the early hours of 6 June 1944. The objective was an 80 km stretch of the Normandy coastline. An armada of 7000 ships planned to land 175,000 men, 50,000 vehicles and all their equipment by day’s end. 11,000 aircraft, oil pipelines under the English Channel and even giant Mulberry Harbours would be towed across the sea.

Neptune

Operation Neptune was the naval element of the Overlord plan. 7,000 vessels from battleships to landing craft, Neptune was truly an allied effort. British, American, Canadian, French, Norwegian, Dutch, Polish and Greek vessels all played a part in enabling the landing’s success.

The Landings

The Allies planned to land on 5 beaches code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. The flanks or sides of the planned beachhead would be secured by airborne forces dropped during the night and early morning on 5/6 June.

Pegasus Bridge

Strategically important, the bridges over the Caen Canal and Orne River had to be captured to enable Allied tanks to operate east of the river, and prevent German counter-attacks against the landings.

Seized by a daring glider assault the bridges were successfully captured by Major John Howard’s D Company, 2nd Battalion, Ox and Bucks Light Infantry at just after midnight, 6 June 1944. Once captured it was vital Major Howard’s men held the bridges against counter-attacks until relieved by Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade at 1 pm.

Merville

In the area immediately east of Sword Beach, some 4,800 elite airborne troops landed by parachute and glider. Men of the 9th Parachute Battalion took the German coastal battery at Merville that threatened the British landing beaches.

US Paratroops

The American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions secured the flanks of the US beaches. However, the 6,600 men dropped were badly scattered that reducing their initial effectiveness, although this did confuse the German defenders. The paratroopers successfully secured the exits from Utah Beach and captured bridges en route to Carentan.

The Story of D-Day, part Two

The American Beaches

Utah Beach

The D-Day landings started at the low water mark on a rising tide at 06.30hrs in the US sector and 07.30hrs for the British.

Strong coastal currents and obscuration of landmarks due to smoke from naval bombardment meant American invasion forces landed 2,000 yards south of their planned objective on Utah Beach. Luckily the area where troops from the 4th Infantry Division actually landed was less heavily defended, and casualties were mercifully light.

Pointe du Hoc

Just as Pegasus Bridge was vital to the success of the British landings so Pointe du Hoc was important to the Americans. Intelligence reports prior to the landings indicated that six 155mm guns in concrete emplacements sat atop a 177ft cliff. The guns threatened the landings on Utah and Omaha Beaches and had to be destroyed.

The elite 2nd Ranger Battalion was tasked with destroying the guns at Pointe du Hoc by direct assault from the sea, which meant scaling the cliffs while under fire. However, when the Rangers fought their way up to the gun emplacements they found them empty. The guns had been moved inland. Later, the guns were found and destroyed.

Omaha Beach

The most difficult terrain and heavily defended sector, Omaha Beach was the objective of the US 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions. At 5.40 am amphibious DD tanks launched 6,000 yards offshore, nearly all sinking in the heavy seas.

Only 5 tanks made it ashore to support the infantry landings. All but one of the 105mm field artillery guns also vital to the landings were lost. To make matters even worse, the naval and air bombardment had done little to reduce the German defensive positions commanding the exposed beach.

Seasick, heavily laden, troops of the nine companies in the first assault wave were decimated by German machine-gun, mortar and artillery fire. Those troops lucky enough to make it across the open beach took cover behind the sea wall.

The assault on Omaha initially stalled. However, gradually men formed small groups and started fighting their way up the bluffs that overlooked the beach. Later, navy destroyers came dangerously close to shore to give much-needed fire support. By day’s end, Omaha Beach was in American hands.

Brigadier General Norman “Dutch” Cota, several NCOs and Privates received decorations for gallantry during the action at "Bloody Omaha".

Today, 3 June 2019, we post a short video taken back in June 2010 on a visit to Omaha Beach and the American Cemetery and Memorial.

The Story of D-Day, part Three

The British, French and Canadian Beaches

Gold Beach

Westernmost of the British/Canadian beaches, code-named Gold, were assaulted by the 50th Division of the British XXX Corps. Specially developed armoured vehicles were landed ahead of the infantry to deal with beach obstacles, mines and the sea wall. Some 2,500 obstacles and mines needed to be cleared from Gold Beach alone. Allied forces quickly overcame German defences and moved inland.

During the advance of the 69th Brigade, Company Sergeant Major, Stan Hollis of the Green Howards won the Victoria Cross, for repeated acts of valour, Britain’s highest military honour. This was the only VC won on D-Day.

Juno Beach

Canada made a terrific contribution to the Allied war effort. Juno Beach was assigned to the Canadian 3rd Division. Like the British, the Canadians used special armoured vehicles to help overcome beach obstacles, mines and strong points. These vehicles were nick-named Hobart’s “funnies” after their creator Major General Sir Percy Hobart.

The town of Courseulles was strongly defended by the Germans but duly taken. The Queens Own Rifles suffered severe casualties crossing the beach at Bernieres. The Canadians made contact with 50th Division on their right by day’s end.

Sword Beach

The easternmost landing zone, Sword Beach, was assaulted by the British 3rd Division. The 3rd Division’s objectives were perhaps the most ambitious of the D-Day operation: capture or mask the Norman city of Caen by nightfall. The 3rd Division also knew it was likely to be counter-attacked by tanks of the German 21st Panzer (Armour) Division.

British intentions to quickly move off Sword Beach and drive inland were held up by resistance from German strong points. British troops reached Lebisey Wood, just three miles short of Caen, but could advance no further.

Special Forces - The Commandos

French Commandos led by Philippe Kieffer took Ouistreham casino and secured the canal gateway. However, the French suffered heavy casualties and Kieffer was wounded twice during the fighting.

Commandos of the 1st Special Service Brigade landed on the 'Queen Red' sector of Sword Beach at approximately 8.40 am, 6 June 1944. Commanded by Brigadier Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, the 1st Special Service Brigade’s mission was to push inland and link up with the lightly armed British 6th Airborne Division holding Pegasus Bridge and bridge over the Orne River.

Today, we have added 241 photos to our Flickr site taken during visits to the D-Day beaches, Pegasus Bridge Memorial and Museum, Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial, Omaha Beach Memorial Museum, Airborne Museum, Sainte-Marie-du-Mont and Sainte-Mère-Église in 2010 and 2014.

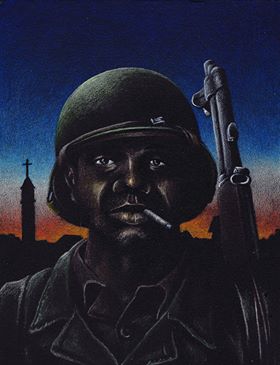

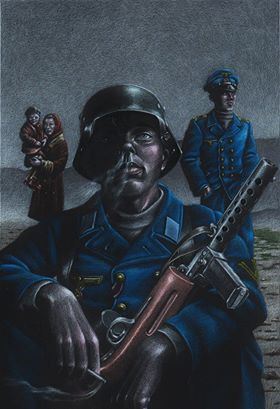

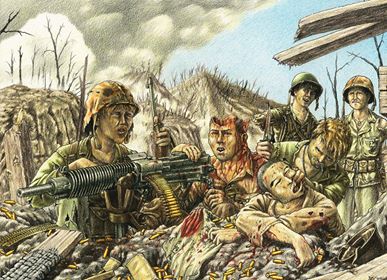

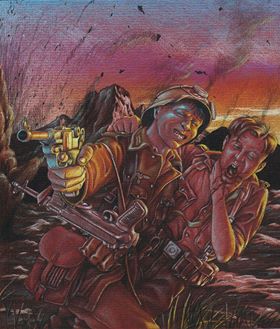

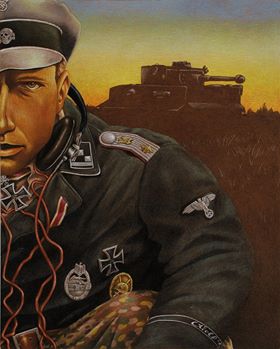

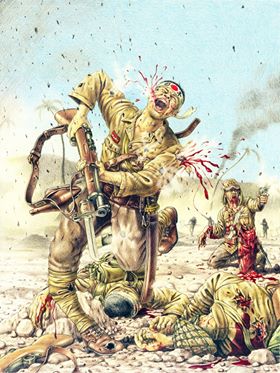

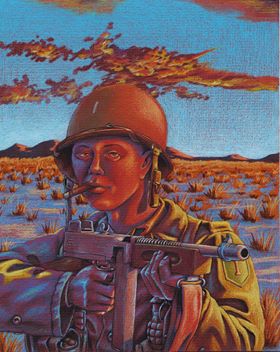

WW2 Artwork of Michael Akkerman

In this blog post, we showcase the emotive, World War Two-inspired artwork of Michael Akkerman from the famous faces of Audie Murphy and Eugene Sledge to the bloody realities of the battlefield.

Michael Akkerman is an American artist whose work is heavily influenced by World War Two (WW2) military history. Michael has kindly allowed The War Years to show some of his work here. Probably the most recognised subject of Michael’s work is Hollywood legend, Audie Murphy. He was one of the most decorated American soldiers of WW2, winning the Medal of Honor aged 19. After the war, Murphy had a successful acting career, as a songwriter and horse breeder. Sadly, he was killed in a plane crash in 1971. He was only 45 years old. One of Michael’s pictures is inspired by an episode taken from Murphy’s wartime autobiography, where he felt compelled to shoot a badly wounded young German soldier as an act of mercy.

Eugene Sledge is another name that will be familiar to many people with a passing interest in the Second World War. He served in the US 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division fighting in the Pacific. His book, ‘With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa’ became a bestseller when published in the 1980s. His book and Robert Leckie’s ‘Helmet for My Pillow’, also served as inspiration for the HBO miniseries The Pacific. The savage, relentless fighting of the Pacific campaign had a dehumanising effect on many of the combatants. However, somehow, Eugene Sledge was able to hold onto his humanity amidst the horror, which is vividly illustrated in Michael Akkerman’s artwork.

Made famous by Nazi propaganda and a legend by the battle of Villers-Bocage, Michael Wittmann was a German tank ace with an impressive tally of 138 kills, mainly achieved on the Russian Front. He is also the subject of one of Michael Akkerman’s paintings. A week after the D-Day landings, SS-Hauptsturmführer Wittmann and his Tiger tank bumped into the forward elements of the British 7th Armoured Division. Wittmann attacked the British column and destroyed 14 tanks, 15 personnel carriers and two anti-tank guns in an engagement that lasted about 15 minutes. Wittmann was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords and became a propaganda star. However, he would be killed just two months later. His remains would not be found and positively identified until 1983.

As well as the famous and infamous, Michael Akkerman’s paintings capture some of the more mundane and human elements of the Second World War, from the black ‘Buffalo Soldiers’ of the US Army to the hardships of the North Africa campaign. He also depicts the bloody realities of the Japanese Banzai charge and the lethal efficiency of the German MG-42 machine guns used to defend Omaha Beach on D-Day. To learn more about Michael’s artwork or to get a quote for a commission, you can find him on Facebook.

Face to Face with the German Tiger tank

In this article, we look at the merits and deficiencies of the German Tiger tank during World War Two, and the muddled strategic thinking that drove the project forward.

The Tiger tank (Panzerkampfwagen VI Tiger Ausf. E) entered service at the end of 1942. It was not a great start. The tank was deployed over unsuitable terrain, limiting its effectiveness. The early production Tigers were plagued with technical problems including dangerous engine fires. Many of these early teething problems were symptoms of the tank being rushed into service without adequate development and testing. However, the Tiger was also over-engineered. The result was a highly complex, often temperamental weapons system that required extensive preventative maintenance and careful handling.

Fighting the Wrong War

Manufactured by Henschel, the Tiger I Ausf. E was the product of creaky strategic thinking. The Tiger was not built in response to Soviet tanks like the T-34 and KV-1. Instead, the Tiger was designed as a “sledgehammer” to smash holes in the enemy’s lines, which support units could then exploit. However, the Germans were already fighting a largely defensive war by late 1942. The days of the blitzkrieg were over. A far better solution would have been to concentrate all manufacturing resources on producing the reliable, very effective Panzer IV main battle tank (MBT).

60 Tonne Sledgehammer

Although the Tiger had many deficiencies, it was not without merit. In the hands of a well-trained and experienced crew who understood the Tiger’s advantages, the tank could prove a formidable opponent. Tank design is about achieving the right balance of mobility, armour and firepower so the vehicle can perform its primary task. Clearly, the Tiger was designed as a sledgehammer, and that’s what the panzer forces got. The Tiger weighed in at just under 60 tonnes, with 100mm frontal armour, 80mm side and rear armour, two MG-34 machine guns, and a high velocity, flat trajectory 88mm main gun.

40 Percent Reliable

The Tiger’s 88mm main gun fired both armour piercing (AP) and high explosive (HE) shells. Officially, the tank could store 92 rounds. However, crews typically packed as many additional shells into every available space as possible. Although the tank was underpowered by the Maybach HL230 700-horsepower petrol engine, it was surprisingly quick and agile on good ground. A semi-automatic gearbox and steering wheel also made the tank easy to drive. Nevertheless, even when the tank was well maintained and supported by a good workshop company, the Tiger’s overall reliability was abysmal. Most Tiger Is were only operational 40 per cent of the time. The reliability of other Tiger variants such as Tiger II Ausf. B, Panzerjager and Jagdtiger were even worse.

Recovery No Easy Task

Naturally, broken down and battle-damaged tanks need to be recovered, whenever possible. Unfortunately, the Tiger’s size and weight often worked against easy recovery. Typically, it took two or three prime movers (tractors) to tow a Tiger to safety. Panzer units were under strict orders not to use one Tiger to tow another, as this could result in damaging the second tank. However, necessity often trumped orders and Tigers frequently towed one another. Later, specialist recovery tanks were introduced, such as the Bergepanther, but these vehicles were always in short supply.

The Importance of Training

How well or poorly an individual tank performs is mainly reliant on the quality and training of the crew. As the war progressed and losses mounted, the German army struggled to provide adequate manpower or training to its panzer forces. Subsequently, overall performance suffered. However, the Germans valued the lives of their panzer crews, and the Tiger provided a separate escape hatch for each man. Many Allied tanks were not designed as well, resulting in men being trapped inside burning vehicles after they had been hit. When it came to training Tiger crews, the official manual was surprisingly innovative. The Tigerfibel aimed to convey complex battlefield instructions in a simple and memorable manner to young recruits using cartoons, jokes and risqué pictures of women. Even today, you can buy a copy in English translation on Amazon.

The Unsinkable Tiger

Thanks to a combination of thick, seemingly impervious frontal armour, the legendary 88mm gun and copious amounts of Nazi propaganda, the Tiger quickly gained a reputation for impregnability. Of course, the Tiger was as impregnable as the Titanic was unsinkable. In reality, the Tiger’s main value came from its ability to stand off and deal with its opponents at a distance. However, even with mid and late-production improvements, by 1944 the Tiger was fighting a losing battle.

The Victory of Mass Production

The Germans went for quality over quantity in tank production, but a lack of time and resources meant they never really delivered on quality. They also chose to pursue an obsolete military strategy at odds with the realities of their situation. In contrast, the Allies went for simple, reliable vehicles they could mass-produce in vast quantities. Over 110,000 Soviet T-34 and American M4 Sherman medium tanks were manufactured compared with just over 1,300 Tiger I Ausf. E. That’s 85 to one, and only half the Tigers would be fit for service at any time. What’s more, the Allies didn’t stand still. They improved their existing tank forces and introduced new, heavier tanks. The British Comet, for example, entered service in December 1944. Ultimately, the Tiger only ever won the propaganda war. In all other respects, the Tiger was a costly, unreliable failure.

Spitfire September

In this post, we review a Spitfire September. First, we take a look at the new Spitfire documentary film. Next, the Battle of Britain Air Show at IWM Duxford, and finally, John Nichol’s book, Spitfire: a Very British Love Story. Tally-Ho!

The 15th of September is Battle of Britain day. It commemorates a turning point in the struggle for aerial supremacy in the skies over Britain fought by the RAF and German Luftwaffe during the summer and autumn of 1940. German daylight raids would eventually cease by the end of October, and Operation Sealion, the German codename for the amphibious invasion of southern England, would be cancelled. It was Nazi Germany’s first significant defeat. A victory won by a handful of daring pilots from across the globe and two iconic aircraft: the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire. However, one aircraft would go on to capture the hearts and imagination of the nation. Since 1940, the Spitfire has become an enduring symbol of courage, fortitude, ingenuity and Britishness.

Spitfire – Inspiration of a Nation

My own little September love affair with the Spitfire started with the release of the documentary film Spitfire – Inspiration of a Nation, directed by David Fairhead and Ant Palmer. Narrated by Charles Dance, the film is a biography of both the aircraft and the men and women who flew it. The original music score by composer Chris Roe and mesmerising aerial photography by director John Dibbs work beautifully together. The film was the last onscreen interview given by Battle of Britain fighter pilot and author Geoffrey Wellum, DFC. The film is also the last testament of Mary Ellis, who flew 76 different types of aircraft during the war as part of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). Ferrying aircraft between factories and operational squadrons, the ATA played a vital support role. During her career, Mary delivered over 400 Spitfires safely to their destinations. The film also features a sound recording of aero engineer and chief designer of the Spitfire, R.J. Mitchell, who died of cancer before his creation went into service. Spitfire is a great piece of documentary film-making, and definitely worth the purchase price.

Battle of Britain Air Show

The last event to mark the centenary of the RAF’s first 100 years, the Battle of Britain Air Show was held at the IWM Duxford on the 22nd and 23rd of September, 2018. Unfortunately, the weather on Saturday was extremely challenging with heavy, persistent rain all afternoon. Nevertheless, the event organisers, aircraft owners and pilots did an excellent job. The show told the history of the RAF from its founding at the end of World War One to the modern day. Highlights of the display included two de Havilland Vampire jets, Battle of Britain Memorial Flight (Spitfire, Hurricane and Lancaster), a 617 Squadron flypast (Tornado GR4, new F-35 Lightning II and Avro Lancaster) and the Red Arrows. The show closed with a formation of 18 Spitfires. We also got to see iconic warbirds such as the P-51D Mustang, Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Catalina seaplane, Westland Lysander and Soviet Yak 3. Sadly, the MiG-15 was not able to fly due to adverse weather conditions. The Battle of Britain Air Show was a very impressive event, and one I would highly recommend. There’s nothing like seeing 18 Spitfires take to the sky, and listening to the combined roar of all those Merlin and Griffon engines.

Spitfire: a Very British Love Story

Finally, I finished my Spitfire September by reading John Nichol’s book Spitfire: a Very British Love Story. A former RAF pilot, John Nichol knows a thing or two about aerial combat. During the 1991 Gulf War, he was shot down, captured and tortured by Iraqi forces. His book examines the Spitfire’s origins and continued development during the war years when the threat from new enemy aircraft demanded constant innovation. When the Spitfire was finally retired from RAF service in 1957 there had been 47 variants including the Fleet Air Arm’s Seafires. However, the book is really a collection of stories about the different roles the Spitfire played in the lives of frontline pilots such as Allan Scott and Hugh ‘Cocky’ Dundas, and ATA pilots like Diana Barnato Walker. Sadly, unlike the beloved Spitfire, the veterans of the conflict do not endure. John Nichol interviewed around 40 veterans over a three-year period of research and writing his book. By the time it was published only three were still with us. Soon the “greatest generation” will be gone forever, but while Spitfires continue to fly, let us hope they will never be forgotten.