The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We would like to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. And we look at the history of unique World War Two artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

Death and Taxes: Financing Britain’s Wars

Ever wondered why we pay taxes the way we do? Our latest guest blog post uncovers the fascinating wartime origins of the UK tax system.

In this intriguing exploration of British fiscal history, Simon Thomas, Managing Director of Ridgefield Consulting, reveals some of the surprising and intricate relationships between warfare and taxation in the United Kingdom. From medieval scutage to the modern PAYE system, this article reveals how moments of national crisis fundamentally shaped the tax structures we know today. Thomas takes us on a journey through centuries of innovation in public finance, showing how creative solutions to wartime funding challenges evolved into the cornerstone principles of modern taxation. Whether you're a history enthusiast, a tax professional, or simply someone who is curious about how our current system came about, this article offers valuable insights into how national emergencies have consistently driven financial innovation in Britain.

You may wonder what war and taxes have in common. Unbeknownst to many, the two have strong links throughout UK history. Wars, often expensive and prolonged, have frequently driven the Government and historically the Crown to seek new ways to generate revenue through the rise of existing taxes and the introduction of new taxes. Over the centuries, the burden of financing these conflicts has shaped the UK’s modern-day taxation system.

Early Taxation and War

The roots and early intertwining of taxation and war begin in medieval times. In tumultuous Norman England, Henry I often gifted land to his knights or nobles under the ‘feudal system’. In return he expected them to offer their military service, and this was central to supporting and building his military.

If these landholders did not want to offer their service in exchange for the land, they could pay a tax called ‘scutage’ and the King would use this money to hire professional soldiers in their place. This practice became a vital source of funding in war and the Crusades and was adopted further by Henry II.

The Window Tax and Creative Revenue Measures

Over the centuries, financial pressures from ongoing wars pushed the government to come up with creative, controversial, and sometimes unusual, forms of taxation. One famous example was the window tax, introduced in 1696 under William III. This tax was designed as an indirect method to tax wealthier households without imposing a formal income tax. Homeowners were taxed based on the number of windows in their homes, as larger homes with more windows were often owned by the wealthier classes. However, to avoid the tax, many property owners began bricking up their windows, giving rise to the term “daylight robbery.”

Other unique taxes have followed in history, like the hearth tax, which charged per fireplace, and the hair powder tax, imposed on those who wore powdered wigs—a symbol of wealth at the time. These inventive taxes highlight how the government’s need for revenue during times of crisis arose. Many of these policies, despite their unusual nature, set the foundation for modern progressive taxes.

The Napoleonic Wars: Income and Inheritance Tax

The Napoleonic wars (1799-1815) marked a turning point in taxation and, to finance its immense costs, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger introduced income tax in 1799. This was the first taxation of its kind on personal earnings and, even though it was originally meant as a temporary measure, set the stage for modern taxation.

The birth of inheritance tax was brought in initially known as ‘legacy duty’ under George III's reign, a tax was imposed on property passed through wills to raise revenue for the government. Legacy tax was levied on how close the relationship of those who inherited was to the deceased. This tax later evolved in the late 1800s as the wars needed more revenue and saw the introduction of succession duty which would tax the whole of the inherited state like today's form of inheritance tax.

The World Wars and Expansion of the Tax System

War is expensive for all; however, the government realized that some industries were profiting from ongoing troubles, for instance, arms manufacturers. During the First World War (1914-1918), because of this, they introduced an excess profits tax on profits that were above their normal pre-war level. This tax was levied at 50% on the profits that surpassed the normal level, with a £200 deduction per year for each business.

The Second World War (1939-1945) saw an expansion of these wartime taxes, with significant increases in income tax and other goods and services, to help raise the money needed to support the war effort. In 1938 they decided to increase income tax, the standard rate was increased to (27.5%) 5 shillings and 6 pence.

Additionally, a surtax, like today's additional tax bracket, was introduced: incomes over £50,000 were subject to a 41% surtax on top of the standard rate, meaning income below £50,000 was taxed at 27.5%, and any income above this threshold faced the higher surtax rate.

To streamline tax collection, the PAYE (Pay As You Earn) system was introduced in 1944 and now some 10 million people are paying direct taxation. This system allowed employers to deduct income tax directly from employees’ wages on a weekly or monthly basis, making tax collection more efficient and forming the basis of the modern income tax system.

Recovering from World War II, the government faced the financial challenge of rebuilding the country, leading to further increases in taxes, particularly inheritance tax. Rates soared from below 60% to as high as 80% by 1969, which is a stark contrast to today's rate of 40%.

In summary, the history of taxes has always been intertwined with wars in the UK and shows how taxation has often been a balancing act between government goals and public needs. These taxes, originally meant to be temporary, have become a lasting part of today’s system, reminding us of how times of crisis can shape what society expects from taxation.

About the Author

Simon Thomas, Managing Director of Ridgefield Consulting. Simon has a longstanding background in tax and accounting, starting with his father, Brian Thomas, who is a Chartered Accountant. Simon trained in London, at one of the Big4 – EY, where he gained expert knowledge and experience. Simon started Ridgefield Consulting in 2010. In April 2021, he expanded the business by acquiring a sister practice Kench & Co.

Sources:

J.R.T. Hughes, Financing the British War Effort, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Steven A. Bank & Kirk J. Stark, War & Taxes, Journal of Scholarly Perspectives, 2008

Strategic Insights from the Battle for Crete

Operation Mercury - the Battle for Crete in 1941 - was a ground-breaking airborne invasion. This historic event offers modern organisations valuable lessons in strategy, leadership, and adaptability. By examining the successes and failures of this battle, we can gain insights into effective decision-making and resilience in today’s competitive business world.

In May 1941, the idyllic Mediterranean island of Crete, a strategic location for controlling the region, became the stage for one of the Second World War’s most daring and innovative military operations. Operation Mercury, Nazi Germany's airborne invasion of Crete, marked a turning point in military tactics and offers valuable lessons for modern business leaders. This blog post explores why the German forces succeeded against British and Commonwealth defenders, and what today's organisations can learn from this historic battle.

The German Gambit for Crete: Innovation and Risk

The brainchild of Luftwaffe General Kurt Student, Operation Mercury represented a huge gamble by the German high command. Prior to this operation, no military force had ever tried to capture a whole island mainly through airborne assault. According to one of his closest aides, Student possessed the unusual ability to combine his inclination for the new, unconventional and adventurous with a working method based on meticulous staff work and precise attention to detail. As Mark Bathurst notes in his article for New Zealand Geographic, “Operation Mercury - the invasion of Crete by Nazi Germany - began on 20 May 1941, when gliders and paratroops (Fallschirmjäger) swooped through the dust and smoke thrown up by Luftwaffe bombs and cannon”. The Germans employed innovative tactics such as using silent gliders to land troops behind enemy lines, catching the defenders off guard.

This innovative approach surprised the Allied defenders, despite their superior numbers and defensive positions. The Germans’ willingness to embrace new tactics and technologies paid off, albeit at a high cost in casualties. Between 20 May and 1 June 1941, the Germans suffered 3,352 casualties. However, we must not forget the immense human cost paid by the Cretans during the Nazi occupation, resulting in the deaths of more than 3,400 individuals.

For business leaders, this underscores the potential rewards of innovation and calculated risk-taking. Companies that dare to challenge conventional wisdom and pioneer new approaches, such as adopting disruptive technologies or entering untapped markets, often gain a significant competitive advantage. However, it is crucial to balance innovation with proven methods and have contingency plans in place, as the high casualty rate among German paratroopers demonstrates.

Allied Failures: The Perils of Poor Communication and Complacency

Despite having advance knowledge of the German invasion plans through Ultra intercepts (signals intelligence), the Allies failed to mount an effective defence. This failure stemmed from several factors, including poor communication, complacency, and ineffective leadership.

As one historical account points out, “The Allied forces on Crete were a mix of British, Australian, New Zealand, and Greek troops, with unclear command structures and poor coordination”. This lack of clear leadership and communication channels severely hampered the defenders’ ability to respond effectively to the German assault.

Moreover, Allied commanders, including New Zealand’s General Bernard Freyberg, seemed overly concerned about a potential seaborne invasion, diverting crucial resources away from the defence of key airfields. This misallocation of forces proved disastrous when the Germans seized control of the Maleme airfield, allowing them to fly in reinforcements and ultimately secure victory.

For businesses, this serves as a stark reminder of the importance of clear communication, effective leadership, and the dangers of complacency. Even with superior resources or market intelligence, companies can fail if they do not have systems in place to act on information quickly and decisively. Leaders must ensure that all team members are aligned with strategic priorities and can adapt swiftly to changing circumstances.

The Power of Seizing Opportunities

Despite heavy initial losses, the German forces managed to capture the critical Maleme airfield, west of Chania. This success allowed them to fly in reinforcements and ultimately turn the tide of the battle. As Johann Stadler, a German veteran, recalled, “I was very proud. It was the first time in war history an island was conquered from the air”.

This aspect of the battle highlights the importance of rapidly capitalising on opportunities, even in the face of setbacks. In business, the ability to quickly identify and exploit key opportunities, such as emerging market gaps or shifting customer preferences, can make the difference between success and failure. Leaders must cultivate a culture of agility and empower their teams to seize chances when they arise.

Adapting to Changing Circumstances

The battle for Crete also demonstrates the critical importance of adaptability. The Germans had to adjust their plans on the fly when they encountered stronger-than-expected resistance. Conversely, the Allies’ rigid adherence to their initial defensive plans, despite changing circumstances, contributed to their defeat.

For business leaders, this underscores the need for agility and the ability to rapidly adjust strategies when market realities do not align with expectations. Successful companies are those that can pivot quickly in response to unexpected challenges or opportunities, such as technological disruptions or shifts in consumer behaviour. Building a flexible, responsive organisation is key to navigating today’s fast-paced business landscape.

The Cost of Victory: Long-term Strategic Implications

While Operation Mercury was ultimately successful, it came at a high cost. The heavy casualties suffered by the German paratroopers led Hitler to prohibit future large-scale airborne operations, effectively wasting this specialised resource.

This outcome offers a valuable lesson for businesses about the importance of considering long-term strategic implications when pursuing high-risk, high-reward strategies. Short-term successes that come at too high a cost can ultimately prove detrimental to long-term goals and capabilities. Leaders must carefully weigh the potential benefits of bold moves against their potential downsides and opportunity costs.

Learning from Failure and Setbacks

Although the Allies lost the Battle of Crete, they learned valuable lessons that they applied to later amphibious invasions, such as the landings in Sicily and Normandy. Their ability to adapt and improve their tactics based on the hard-won experience at Crete ultimately contributed to their success in the war. However, it can be argued that the Allies learned some of the wrong lessons from the German victory on Crete. As the war progressed, the Allies amassed considerable airborne forces, but their deployment was infrequent and not always successful. In 1944, Britain was chronically short of infantrymen while thousands of ‘special service’ troops like paratroopers were held in reserve for airborne operations that were frequently postponed or cancelled.

Similarly, businesses must learn to treat failures and setbacks as opportunities for growth and improvement. By conducting thorough post-mortems, identifying root causes, and implementing corrective actions, companies can emerge stronger and more resilient. Leaders who encourage a culture of continuous learning and improvement will have better preparation to face the inevitable challenges of the business world.

Applying Historical Lessons to Modern Business

The Battle for Crete offers a wealth of insights for today's business leaders:

Innovation and calculated risk-taking can provide a competitive edge but must be balanced with proven methods and contingency planning.

Clear communication, effective leadership, and avoiding complacency are crucial, even when you seem to have an advantage.

The ability to quickly seize opportunities and adapt to changing circumstances can be the difference between success and failure.

It is essential to consider the long-term strategic implications of high-risk actions, not just short-term gains.

Failures and setbacks should be treated as valuable learning opportunities for continuous improvement.

By studying historical events like Operation Mercury, business leaders can gain valuable insights on strategy, tactics, leadership, and communication. These lessons, drawn from one of military history’s most daring operations, remain remarkably relevant in today’s fast-paced, competitive business environment. As modern leaders navigate the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, they would do well to remember the hard-fought lessons of Crete and apply them to their own strategic decisions.

References:

Bathurst, M. (2005). Operation Mercury: The Battle of Crete. New Zealand Geographic, Issue 073. https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/crete/

Bell, K. (2006). Battle of Crete: It Began with Germany’s Airborne Invasion—Operation Mercury. Historynet. https://www.historynet.com/battle-of-crete-it-began-with-germanys-airborne-invasion-operation-mercury/

MacDonald, C. (1995). The Lost Battle – Crete 1941.

Rehman, I. (2024). Britain’s Strange Defeat: The 1941 Fall of Crete and Its Lessons for Taiwan. War on the Rocks: https://warontherocks.com/2024/05/britains-strange-defeat-the-1941-fall-of-crete-and-its-lessons-for-taiwan/

The defence and loss of Crete, 1940-1941 (Part 1). (2020). The National Archives. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/the-defence-and-loss-of-crete-1940-1941-part-1/

The defence and loss of Crete, 1940-1941 (Part 2). (2020). The National Archives. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/the-defence-and-loss-of-crete-1940-1941-part-2/

The Silent Disaster: How Communication Failures Helped Doom Operation Market Garden

As we commemorate Operation Market Garden this September, it's worth reflecting on one of the most ambitious - and ultimately ill-fated - military operations of World War II. Launched in September 1944, Operation Market Garden aimed to secure a series of nine bridges in the Netherlands, potentially paving the way for a swift advance into Germany. It was a massive undertaking, involving over 34,000 airborne troops and 50,000 ground forces. Yet, what began with high hopes ended in a costly failure, partly because of a communications breakdown.

Operation Market Garden: 17 to 25 September 1944

As we commemorate Operation Market Garden this September, it's worth reflecting on one of the most ambitious - and ultimately ill-fated - military operations of World War II. Launched in September 1944, Operation Market Garden aimed to secure a series of nine bridges in the Netherlands, potentially paving the way for a swift advance into Germany. It was a massive undertaking, involving over 34,000 airborne troops and 50,000 ground forces. Yet, what began with high hopes ended in a costly failure, partly because of a communications breakdown.

At the heart of Market Garden's communication crisis was the inadequacy of the radio equipment. The British Army's standard radio set, the Wireless Set No. 22, proved insufficient for the task at hand. These radios had a maximum range of around six miles under ideal conditions, yet the Corps Headquarters was positioned a distant 15 miles away. To compound matters, the terrain around Arnhem presented additional challenges that the planners had failed to fully account for. The Arnhem area was characterised by woodland and urban buildings. These physical obstacles severely interfered with radio transmissions, further diminishing the already limited range of the No.22 sets. As a result, what should have been a vital lifeline for the paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division fighting desperately to hold the north side of the bridge at Arnhem became a silent witness to their isolation and eventual defeat.

Interestingly, a potential solution to these communication problems was literally at hand. The Netherlands boasted an extensive and sophisticated telephone network, largely intact despite years of German occupation. This network was remarkably resilient, comprising three interconnected systems: the national Ryks Telefoon system, the Gelderland Provincial Electricity Board's private network, and a clandestine network operated by Resistance technicians. Even when key exchanges were disrupted, the Dutch were still able to communicate using alternative routings.

Yet, astonishingly, Allied planners failed to fully leverage this resource. This oversight raises profound questions about the rigidity of military thinking. Why did the Allied command, known for its adaptability in other areas, fail to pivot to this seemingly obvious solution? The answer likely lies in a combination of factors: overconfidence in existing systems, security concerns, lack of familiarity with local infrastructure, the fast-paced nature of the operation, and a wariness of the Dutch Resistance.

British XXX Corps cross the road bridge at Nijmegen

The consequences of this failure were dire. While some units made limited use of the phone system, the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem - where the need was most critical - did not. They made no attempt to convey their urgent need for supplies or relief via the phone system to the corps headquarters. Ironically, Dutch agents inside the 82nd Airborne's landing area used the phone system early on D+1 to inform the 82nd that “the Germans are winning over the British at Arnhem” - the first indication that the 1st Airborne was in serious trouble.

In the face of radio failures, the Allied forces resorted to various other communication methods, each with its own limitations. Carrier pigeons proved unreliable, with many birds failing to deliver messages. Traditional forms of communication like land lines, runners, and dispatch riders were vulnerable to enemy fire and the chaos of battle. The artillery net ended up being one of the more reliable communication methods, allowing for effective artillery support and occasional relay of messages to higher command.

The communication failures during Operation Market Garden offer valuable insights into military organisational thinking. They underscore the importance of flexibility, the need to understand and potentially leverage local infrastructure, the crucial role of contingency planning, and the necessity of fostering a culture that encourages quick problem-solving and innovative thinking at all levels of command.

It's worth noting the contrast between the German military's mission-type tactics (Auftragstaktik), which emphasized flexibility and initiative, and the British Army's reliance on detailed orders and strict adherence to commands. This difference in command styles meant that German forces could often exploit opportunities more rapidly, while British forces maintained tighter control but at the cost of agility.

As we reflect on the events of eighty years ago, it's clear that the lessons learned extend far beyond the realm of military strategy. In any high-stakes endeavour, the ability to communicate effectively - and to adapt when primary methods fail - can mean the difference between success and catastrophic failure. The underutilisation of the Dutch phone system stands as a poignant example of how overlooking available resources can have far-reaching consequences.

The story of Operation Market Garden serves as a stark reminder of the critical role that effective communication plays not just in military operations, but in any complex undertaking. It's a lesson that remains relevant today, in fields ranging from business to disaster response. As we face our own challenges in an increasingly connected world, let's not forget the silent disaster that unfolded in Holland eighty years ago - and the valuable lessons it still has to teach us.

References

1. Middlebrook, M. (1994). Arnhem 1944: The Airborne Battle. Westview Press.

2. Ryan, C. (1974). A Bridge Too Far. Simon & Schuster.

3. Kershaw, R. (1990). It Never Snows in September: The German View of Market-Garden and the Battle of Arnhem, September 1944. Ian Allan Publishing.

4. Buckley, J. (2013). Monty's Men: The British Army and the Liberation of Europe. Yale University Press.

5. Beevor, A. (2018). The Battle of Arnhem: The Deadliest Airborne Operation of World War II. Viking.

6. Powell, G. (1992). The Devil's Birthday: The Bridges to Arnhem 1944. Leo Cooper.

7. Badsey, S. (1993). Arnhem 1944: Operation Market Garden. Osprey Publishing.

8. Hastings, M. (2004). Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 1944-1945. Alfred A. Knopf.

9. Zaloga, S. J. (2014). Operation Market-Garden 1944 (1): The American Airborne Missions. Osprey Publishing.

10. Clark, L. (2008). Arnhem: Operation Market Garden, September 1944. Sutton Publishing.

11. MacDonald, C. B. (1963). The Siegfried Line Campaign. Center of Military History, United States Army.

12. Bennett, D. (2007). Airborne Communications in Market Garden, September 1944. Canadian Military History, 16(1), 41-42.

13. Greenacre, J. W. (2004). Assessing the Reasons for Failure: 1st British Airborne Division Signal Communications during Operation 'Market Garden'. Defence Studies, 4(3), 283-308. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1470243042000344777#d1e290

Book Review: SAS - Duty Before Glory: The True WWII Story of SAS Original Reg Seekings

Book Review: SAS - Duty Before Glory: The True WWII Story of SAS Original Reg Seekings.

There are an estimated 300 to 500 books that delve into every aspect of Britain's elite Special Air Service (SAS). With the origins of the SAS having been so extensively explored in books, documentaries, and TV dramas, one might think there is little new to say. Nevertheless, Tony Rushmer’s ‘SAS - Duty Before Glory’ brings to light the remarkable tale of Reg Seekings, one of the SAS's original members and most decorated non-commissioned officers of World War II. Set for release on 26 September 2024 by Michael O'Mara Books, this biography is a gripping account of bravery, camaraderie, and the extraordinary feats of an ordinary man.

Summary

Rushmer's narrative traces Seekings' journey from his humble beginnings in the Cambridgeshire Fens to his pivotal role in the SAS during World War II. The author draws upon archive recordings and previously unseen family documents to paint a vivid picture of Seekings' life, from farm labourer's son and amateur boxer to highly decorated squadron sergeant major.

The book delves into Seekings' involvement in daring behind-the-lines operations across North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. It recounts hair-raising, and sometimes quite shocking experiences, including surviving a bullet to the base of his skull in France and being one of the first Allied soldiers to enter Belsen concentration camp.

SAS: Seekings and Seekings

Rushmer's meticulous research shines through in the level of detail provided. The use of Seekings' own handwritten accounts of operations adds a layer of authenticity and immediacy to the narrative. The author's journalistic background is evident in his ability to weave together personal anecdotes with a broader historical context, creating a compelling read.

The book doesn't shy away from presenting Seekings as a complex, frequently violent character. Seekings appeared to be one of those rare people who was able to remain calm and clearheaded, no matter how urgent or stressful the situation was. He was also gifted with incredible luck, repeatedly emerging from combat without a scratch while many of his comrades were killed and wounded.

One of the book's compelling aspects is its exploration of the relationship between Reg and his brother Bob, who followed him into the SAS. While the brothers shared a sporty and competitive nature, it’s evident that Reg possessed an extraordinary inner strength. This mental resilience allowed him to perform his duties consistently, no matter how unpleasant.

In contrast, the narrative paints a poignant picture of Bob's struggle with the intense mental and physical demands of SAS operations. This juxtaposition of the brothers' experiences adds a layer of human interest to the story, highlighting the exceptional nature of Reg's capabilities while also underscoring the immense pressures faced by the original members of the SAS.

Target Reader

‘SAS - Duty Before Glory’ will appeal to military history enthusiasts, particularly those interested in Special Forces operations during World War II. The book's focus on personal experiences and character development also makes it accessible to anyone who enjoys reading about the lives of remarkable characters.

In summary

Tony Rushmer's ‘SAS - Duty Before Glory’ is a welcome addition to the canon of World War II literature. By focusing on the extraordinary life of Reg Seekings, Rushmer provides a fresh perspective on the early days of the SAS and the individuals who shaped its legacy. The book serves not only as a tribute to Seekings but also as a testament to the indomitable human spirit in the face of adversity.

This meticulously researched and engagingly written biography is sure to be a must-read for anyone interested in the early history of the SAS and its original members.

The Lancaster Story: A New Book About a Legendary Bomber

From the moment it entered service in 1942, the Avro Lancaster heavy bomber quickly became an icon. In this blog post, we review The Lancaster Story: True Tales of Britain’s Legendary Bomber a new book by Dr. Sarah-Louise Miller.

As we approach the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings, it is only correct that we remember the aerial battle for Normandy. On the morning of 6 June 1944, Avro Lancaster bombers of 617 Squadron (the Dam Busters) played a central role in Operation Taxable. Their mission was to create a diversion by simulating an invasion fleet on enemy radar screens, misleading the Germans about the actual location of the D-Day invasion. The role of the Lancaster bomber in the success of Operation Fortitude, the deception plan designed to convince the Germans the Allied invasion would land at the Pas-de-Calais, not Normandy, is just one of the missions depicted in a new book called The Lancaster Story by Sarah-Louise Miller.

On 17 April 1944 the Allied Supreme Headquarters issued a directive which stated the primary mission of Bomber Command prior to Operation Overlord, namely the destruction of the Luftwaffe’s air combat strength and the disruption of rail communications to isolate the designated invasion area in Normandy. RAF Bomber Command played a major role in the Transportation Plan, helping to significantly delay German panzer divisions from reaching the landing beaches and subsequent Allied build-up. Having established air superiority over the skies of Normandy, Bomber Command would be repeatedly called upon to support ground forces. Perhaps one of the most heartening sights for Allied troops on the ground was to see waves of British and American bombers streaming relentlessly toward their targets.

The Avro Lancaster

flew more than 150,000 operational sorties, dropped more than 600,000 tons of explosives, and took the Allied fight to Nazi Germany, cementing its place in history as an aviation icon.

From the moment it entered service in 1942, the Avro Lancaster heavy bomber quickly became an icon, and The Lancaster Story vividly recounts its extraordinary tale. The book describes the aircraft’s chronological history from its shaky start as the twin-engine Avro Manchester to the famous Operation Chastise or Dambusters Raid of May 1943. The book also focuses on the immense efforts made by thousands of men and women who joined RAF Bomber Command from across Britain and the Commonwealth during the Second World War. Lastly, the book sheds light on the enduring legacy of this beloved aircraft while briefly discussing the later controversy over the morality of the Allied bombing campaign.

Historian, author and broadcaster, Sarah-Louise Miller brings the story of the Lancaster to life through a combination of archival documents, letters and first-hand accounts from factory workers and aircrew to the civilians who lived near RAF Bomber Command airfields. Miller writes in a straightforward, conversational style and tone, neatly interweaving historical facts and statistics with very human tales of fear, courage, love, and loss that combine to make The Lancaster Story a compelling read. She examines the evolving strategy, tactics, and technical innovations of the air war. She also systematically explains the various jobs undertaken by each of the seven crew members and how quickly they formed tightknit, almost inseparable groups.

Ground crew refuelling and bombing up an Avro Lancaster of No. 75 (New Zealand) Squadron. The bomb load consists of a 4,000lb HC ‘Cookie’ and a mix of 500lb and 1,000lb bombs.

By 1945, a quarter of a million women of 48 different nationalities had served in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). In 1943, WAAFs constituted nearly 16 percent of the RAF’s total strength. Although WAAFs did not serve as aircrew, they were exposed to many dangers working on the home front. They performed around 110 different trades including parachute packing, catering, meteorology, aircraft maintenance, transport, policing, code breaking, reconnaissance photograph analysis, intelligence operations, and air traffic control. One of the roles undertaken by WAAFs was to debrief aircrews immediately after they had returned from a mission. Initially, the RAF believed women would be unsuitable for the job of interrogating exhausted, often traumatized aircrew about their experiences. However, as Miller explains, WAAFs were found to be very effective in conducting debriefs. The women were able to use empathy, patience, and kindness to coax the airmen into talking about what they had seen and experienced. Miller’s book highlights the significant contribution that women made to the war effort, demonstrating courage and dedication in numerous essential roles within the Royal Air Force.

No book, film or documentary can adequately convey what it was like to climb into a Lancaster bomber, night after night, certain in the knowledge that you might never return. Lancaster pilot Stevie Stevens wrote, ‘It was pretty obvious that we couldn’t all survive.’ Bomber Command lost 55,573 aircrews killed. Another 8,400 were wounded and nearly 10,000 taken prisoner. Miller’s book leaves the reader in no doubt that a Lancaster bomber was an extremely hostile work environment. The interior of the aircraft was functional with few concessions to the crew’s comfort. Without heated flying suits and oxygen masks, the crews would freeze or pass out from hypoxia. At any moment, an aircraft might get jumped by enemy night fighters or peppered by chunks of white-hot shrapnel from anti-aircraft gunfire known as Flak. If your aircraft was hit and you had to bail out over hostile territory, then you might be summarily executed by an angry mob of local inhabitants before the German military arrived to take you prisoner. Rightly, Miller examines the incredible mental and physical stresses endured by Lancaster aircrews. Remarkably, only 5,000-6000 airmen were hospitalised or relieved of flying duties due to combat stress and exhaustion. Nevertheless, a rather unsympathetic RAF stigmatised these men with the label ‘LMF’ which stood for Lack of Moral Fibre.

Overall, The Lancaster Story is an accessible, well researched and well written book that I would have no hesitation in recommending. However, I have been left wondering, did we really need another book on the subject? A quick search of a certain popular online retailer returned more than thirty titles on the Lancaster bomber including Lancaster: The Forging of a Very British Legend by John Nichol, The Avro Lancaster: WWII's Most Successful Heavy Bomber by Mike Lepine, and Luck of a Lancaster by Gordon Thorburn. There are two books already in print with the same title, The Lancaster Story, one by Peter March and the other by Peter Jacobs. It has been a while since I read John Nichol’s book on the Lancaster, but I seem to recall that his book does cover a lot of the same ground. I’m sure the author and publisher discussed the pros and cons of producing another title for an already crowded segment of the aviation history market, but perhaps the Lancaster’s enduring appeal along with Sarah-Louise Miller’s celebrity will make certain of book sales. I hope so.

Today, the Lancaster has something of a mixed legacy both at home and abroad. In Britain, the aircraft has become a symbol of patriotism and national sacrifice. However, the bombing campaign against Nazi Germany has also been criticised and condemned by some for the killing of around 600,000 Germans, mostly civilians.

During the 1970s, the Headmaster of my Primary School was both feared and revered by small boys like me. He was a strict disciplinarian with a booming voice and a quick temper, who wasted no time in punishing any misbehaviour. However, he had also been a navigator in a Lancaster bomber and that made him something special to us. As children of the 70s, we had all grown up on a diet of epic British war films like The Dam Busters and spent hours in our bedrooms constructing Airfix model kits of Spitfires, Hurricanes, and Avro Lancaster. We read comic books like Warlord and Battle Picture Weekly. Most stories were set during World War Two and featured characters such as D-Day Dawson, Union Jack Jackson, and Lord Peter Flint, codenamed Warlord. Perhaps unsurprisingly, ‘The War’ has held an enduring fascination for us ever since. As adults, we flock to airshows, museums, military history events and commemorations. We go on battlefield tours and buy books by military historians such as James Holland, Max Hastings, Antony Beevor, and Sarah-Louise Miller. And, occasionally, we rush outside and turn our heads skyward at the distinctive sound of approaching Merlin engines. Then we stand in our carpet slippers and gape at the sight of an Avro Lancaster as it passes overhead.

The Lancaster Story: True Tales of Britain’s Legendary Bomber by Sarah-Louise Miller is published by Michael O’Mara Books Ltd will be available in hardback from 23 May 2024.

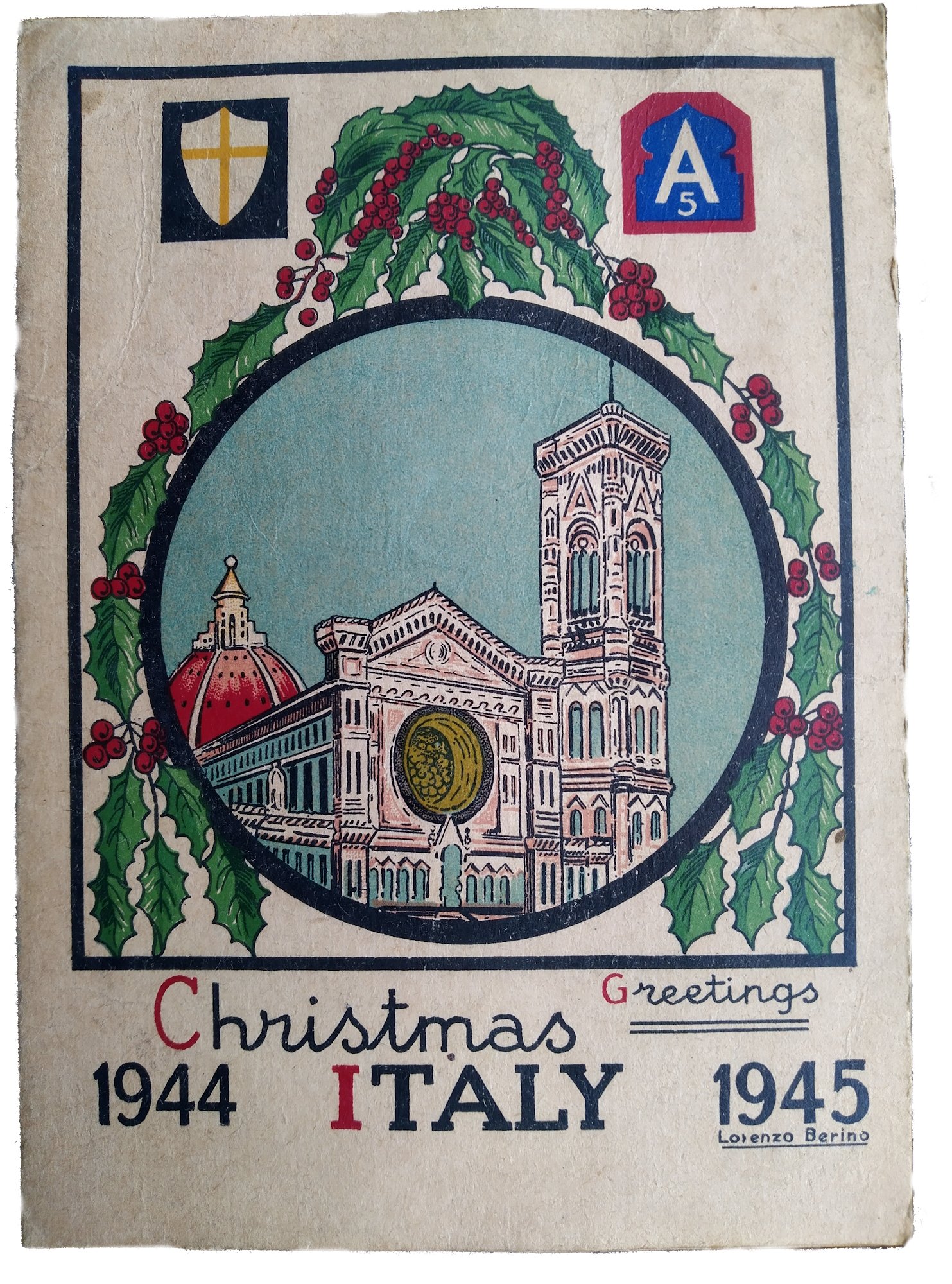

Dick Hewitt and the Desert Air Force

Dick Hewitt served as an Armourer with a mobile fighter squadron as part of the Desert Air Force (DAF) from 1943 to 1945. During Dick’s time in the RAF, he kept a diary, although this was against regulations. Although the diaries are incomplete, they have provided enough clues and information to be able to retell the wartime story of one Leading Aircraftman and his role in the Allied campaign for Italy.

Dick Hewitt served as an Armourer with a mobile fighter squadron as part of the Desert Air Force (DAF) from 1943 to 1945. During Dick’s time in the RAF, he kept a diary, although this was against regulations. Although the diaries are incomplete, they have provided enough clues and information to be able to retell the wartime story of one Leading Aircraftman and his role in the Allied campaign for Italy.

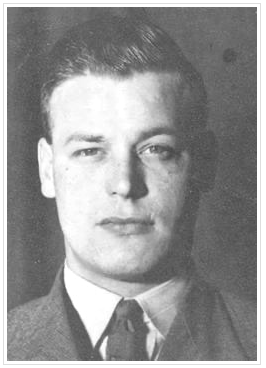

Dick Hewitt was born on Thursday 18 April 1901 in Leicester. Dick passed away on Friday 7 June 1985, aged 84, in Birmingham.

Service in the British Army

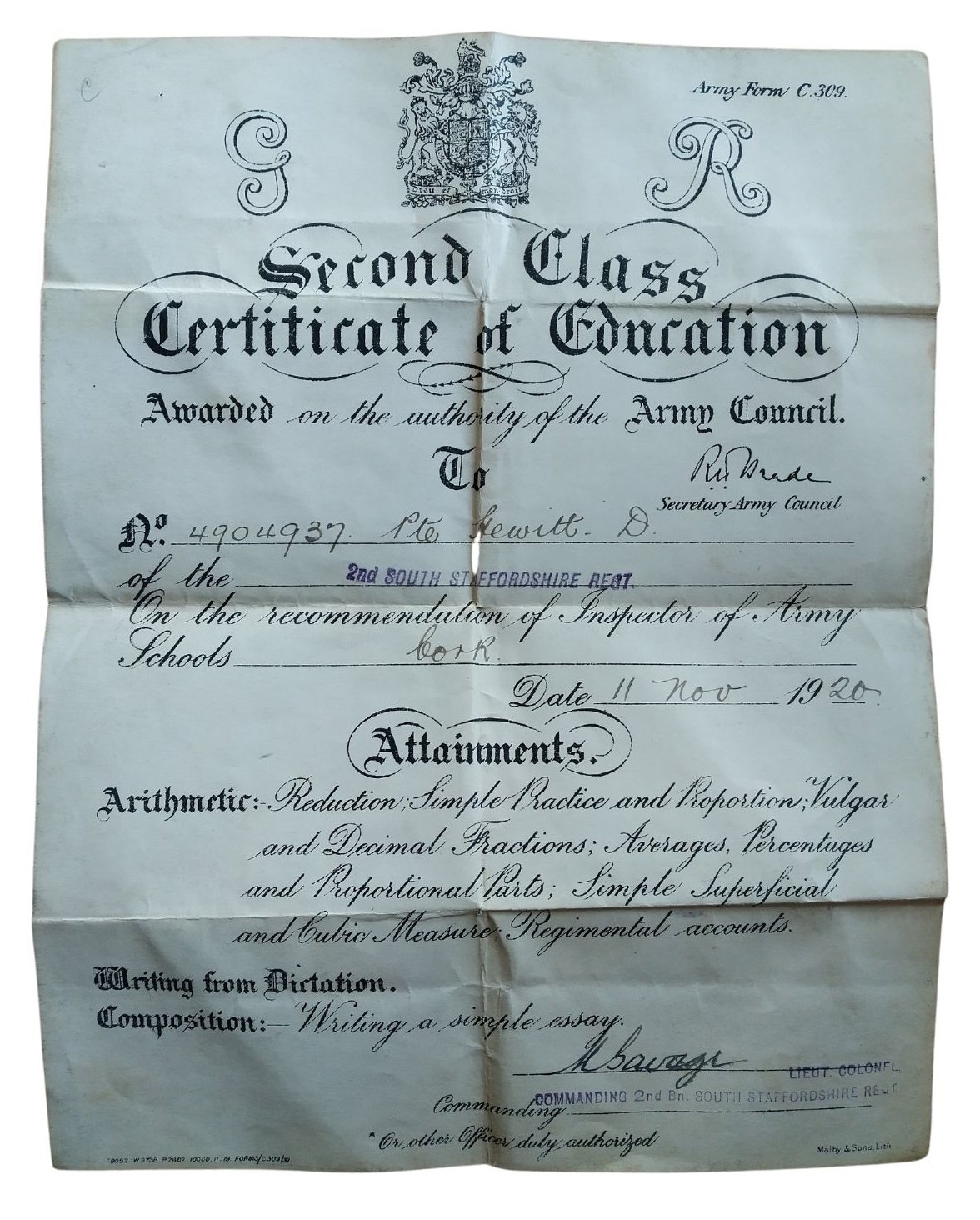

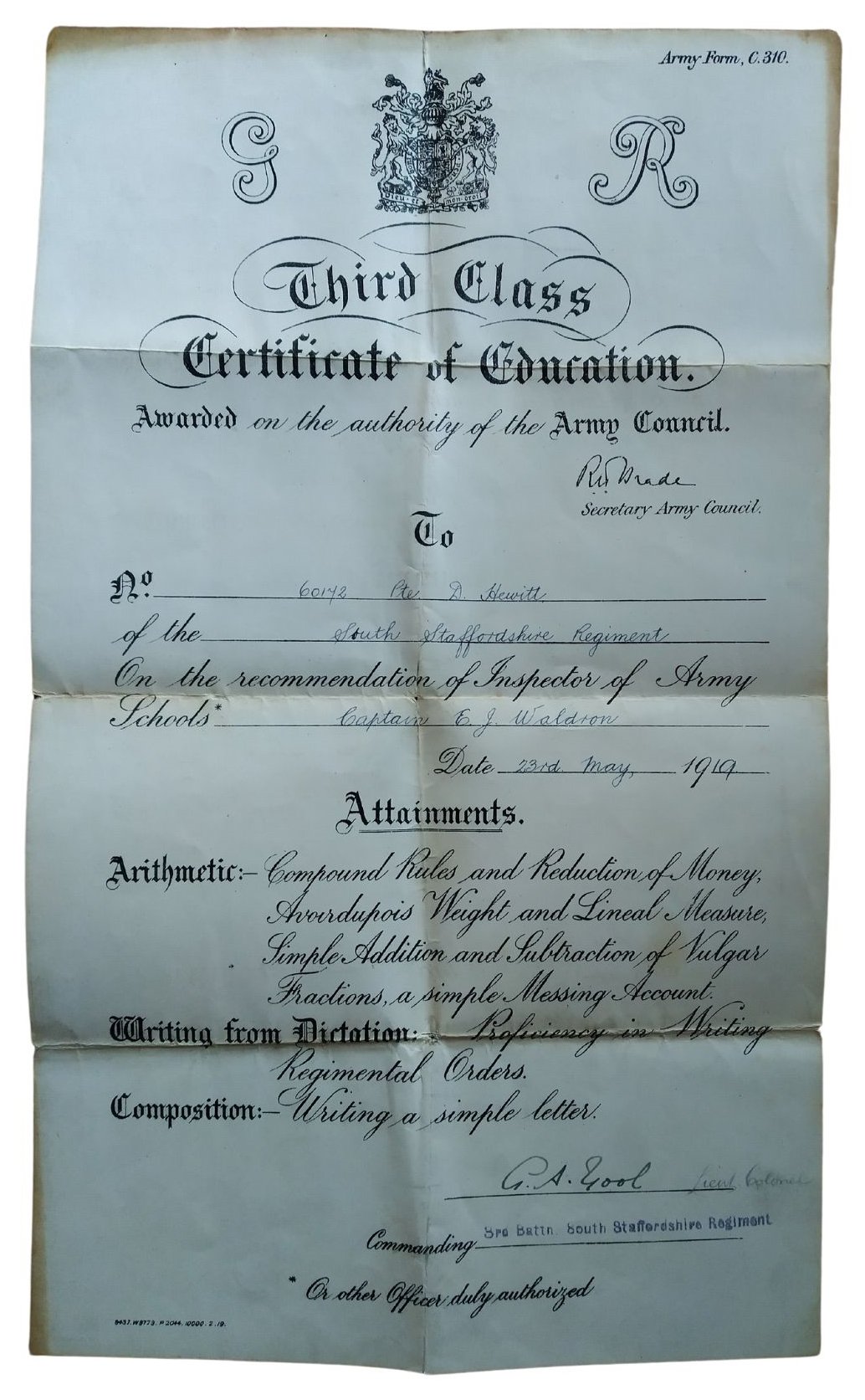

Amongst Dick’s personal papers, I found several Certificates of Education awarded to Private D. Hewitt, the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment issued in May 1919 and November 1920, which suggests that Dick was conscripted into the Army (as conscription did not end until mid-1919). The 2nd Battalion spent the immediate post-war years in Ireland during the War of Independence (1919-21). One of Dick’s Certificates of Education was issued from Cork, which confirms that he was stationed in Ireland. The Corps of Army Schoolmasters was replaced in 1920 by the Army Educational Corps (AEC). A brief search of The National Archives and British Army World War I Service Records, 1914-1920, found no record of Dick’s early military service with the South Staffordshire Regiment.

Dick was in his early to mid-forties during the Second World War. Most of his comrades would have been in their late teens to mid-twenties. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as an older man, it appears Dick’s comrades referred to him as ‘Pops’ based on some post-war correspondence found amongst Dick’s personal papers. Dick was married with two children while serving in the RAF and he sent money home to his family whenever he was able.

Service in the Royal Air Force

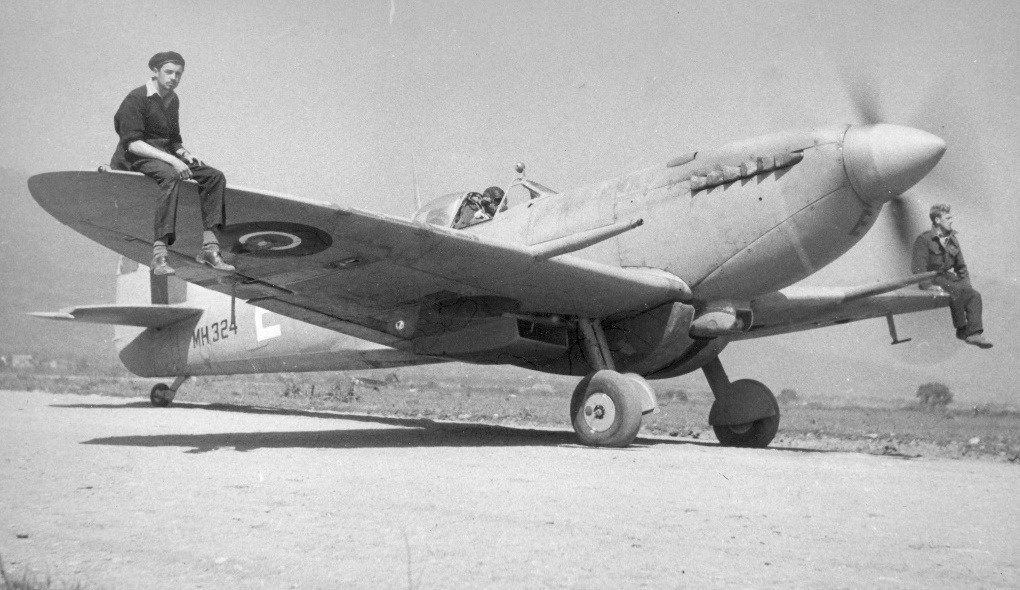

Dick’s RAF Service No: 1468728. He held the rank of Leading Aircraftman (LAC) and qualified as an Armourer. Dick served with 324 Wing, No. 93 Squadron, Royal Air Force, part of the BNAF (British North Africa Force). As part of a highly mobile fighter squadron originally equipped with Spitfire Mk. Vs and later Mk. IXs, Dick served in North Africa, Malta, Italy, Corsica, and southern France.

The Role of the Armourer

As an Armourer with No. 93 Squadron, Dick’s role was to arm the Spitfires of No. 93 Squadron with ammunition and bombs, regularly strip and clean the guns and perform general maintenance. Based on Dick’s diary entries, he also worked on fitting supplementary fuel tanks to the Spitfires, which extended their range.

Diary Entries: UK Training & Posting Overseas 1942

9 January: Left Halton Camp for Kirkham. RAF Halton, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire, was a major RAF training centre. Similarly, RAF Kirkham, Lancashire, was the main armament training centre for the RAF from November 1941.

1942: Passed Armourer’s course, A.C. II. – Aircraftman 2nd class.

30 March 1942: Passed L.A.C. exam – Leading Aircraftsman.

1942: Arrived at RAF Speke. Note: Today, RAF Speke is Liverpool John Lennon Airport.

1942: Promoted A.C. I. - Aircraftman 1st class.

11 November: Left Wareford for overseas. By train to Scotland. Arrived at Greenock at 08.00hrs.

13 November: Boarded the HMT (His Majesty's Transport) Bergensfjord (a former Norwegian ocean liner). Navy, Army, and Air Force personnel were all on board.

14 November: Left Greenock at 05.00hrs heading for the North Atlantic. There are 16 boats in our convoy escorted by Royal Navy Destroyers.

20 November: Nearing the Mediterranean, passed Gib (Gibraltar) at midnight. Could see Tangiers lit up at night.

Tunisia 1942

8 December: Arrived at Souk-El-Arba station (Tunisia) at 08.00hrs. We’re about 40 miles behind the frontline.

19 December: Had a terrible sight to witness as one of the (ditto) ground crews was taken up in the air sitting on the tail of a plane. The kite (RAF slang for aircraft) crashed on landing throwing the man right over the front of the kite. He sustained serious injuries to his legs. Note: During bad or windy weather, it was common practice to have a member of the groundcrew sit on the tailplane of an aircraft as it taxied to its take-off position. Usually, the groundcrew would dismount while the pilot carried out their pre-flight checks.

30 December: Nearly killed when strafed by a Jerry aircraft. Had to dive for cover on the roadside. Learned all the Squadron’s tools were lost when the boat carrying them was torpedoed on 18 December.

The Desert Air Force (DAF) in Tunisia

The Allied campaign in Tunisia started in November 1942. By late March and throughout April 1943, the Desert Air Force (DAF) was conducting bombing and strafing missions (interdiction) on infrastructure, such as bridges, supply routes, Luftwaffe airbases, Tunisian ports, and the capital of Tunis. They also flew missions over Sicily and southern Italy. The aim of the missions was twofold. First, starve Axis forces of everything from fuel and ammunition to food, and thus weaken their ability to resist. The second was to establish Allied air superiority over the battle space and enable the ground forces to make a final push on the Tunisian capital. The DAF also provided close air support to Allied ground forces.

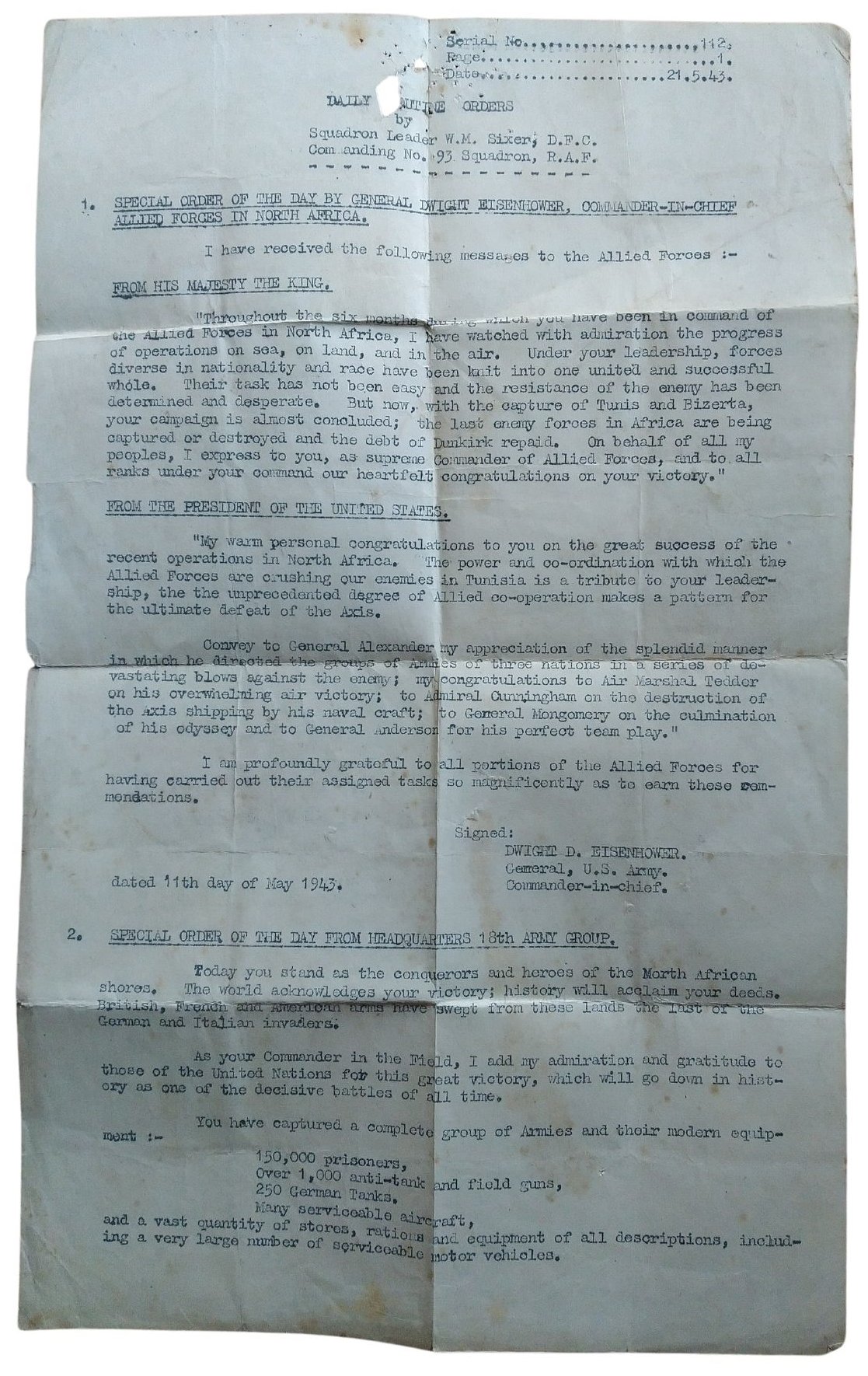

On 7 May 1943, Allied armour rolled into Tunis, taking many Axis troops based in the city completely by surprise. By 10 May, the Luftwaffe had evacuated what aircraft and equipment they could salvage. The capture of Tunis led to an Axis surrender and the capture of around 250,000 prisoners. It was a significant Allied victory.

No 72 Squadron, 324 Wing RAF. Spitfire, North Africa 1943.

Diary Entries: Tunisia 1943

3 February 1943: Jerry bombed drome (aerodrome) in the morning. Three RAF were killed and five wounded. Bombs were released from FWs (Focke Wulf 190 fighter-bombers) while I was having a wash. Eight Spits U.S. (unserviceable).

22 February 1943: Fortresses (B.17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber) dropped bombs on Souk-El-Arba, 25 people killed by mistake. Note: There were two airfields at Souk-El-Arba both located near what was at the time the village of Souk-El-Arba but since 1966 has been known as Jendouba. The site is about 81 miles west-southwest of Tunis.

1 March 1943: Kites on a bomber escort, one Spit and one ME (presumably a Messerschmitt Bf 109) shot down during a dogfight over the drome at 12.30hrs.

2 March 1943: Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham arrived at the drome. Note: Today, Coningham is chiefly remembered as the person most responsible for the development of forward air control parties directing close air support, which he developed as commander of the Western Desert Air Force between 1941 and 1943.

16 March 1943: Dive-bombed without warning. Dived under a kite and watched bombs bursting. AA (anti-aircraft artillery) returned fire. One soldier was killed.

April 1943: Squadron mainly assigned to bomber escort missions. Note: The Allies heavily bombed Axis (Luftwaffe and Italian) airfields and infrastructure such as bridges. Enemy air activity diminished as the Allies' bombing campaign intensified.

7 May: Tunis reported taken.

10 May: Bizerta reported taken. After being reported missing Red Herbert got back to the airfield with 20 released prisoners.

12 May: Thousands of prisoners taken. End of the campaign in Africa.

14 May: Move to a new drome between Tunis and Bizerta. Met thousands of prisoners and passed through the battlefront. Saw plenty of wrecked tanks, etc.

15 May: On new drome. Found a camp bed, very useful. Bags of rifles, etc. Crashed and wrecked Ju-52s all over the airfield and two ME-109s. Had to be careful of boobytraps and mines. Note: The Junkers Ju-52 is a three-engine transport aircraft and was a mainstay of the German Air Force (Luftwaffe).

20 May: Victory Parade at Tunis. Thousands of troops were in the town.

24 May: Went souvenir hunting. Found the famous Ace of Spades Squadron drome. Every kite was either burned out or shot up. Bags of stores lying about. In this diary entry, Dick is referring to the Jagdgeschwader 53 (JG 53) fighter-wing of the Luftwaffe, known as the "Pik As" (Ace of Spades).

26 May: Move to a drome at Mateur, which is situated between Bizerta and Tunis.

8 June: Drove to Sfax harbour (south of Tunis) and boarded a Landing Ship, Tank (LST).

9 June: Arrived in Malta.

Dick Hewitt, on the left, sitting on the wing of a Spitfire. Date and location of photograph unknown.

Malta 1943

20 June: The King arrived in Malta. He visited the drome.

24 June: Sir Archibald Sinclair (Secretary of State for Air) visited the drome in the afternoon and gave a speech. He thanked us for our work in North Africa.

10 July: Operation HUSKY. Sicily was invaded by troops at 02.30hrs. Kites on dawn sweeps (sorties) over Sicily. Worked until 23.00hrs.

Operation HUSKY, Allied Invasion of Sicily, 9 July - 17 August 1943

Prior to an Allied invasion of the Italian mainland, it was necessary to capture the island of Sicily. Axis forces based on Sicily were resupplied across the Messina Strait. The key target of the invasion was the port of Messina, the link to the Italian mainland. But it was heavily defended and its distance from North Africa meant the Allies could not attack it directly.

A major concern and threat to the invasion fleet was the Italian island of Pantelleria, about 50 miles from the Tunisian coast and halfway to Sicily. The island could be used by Axis forces to attack the invasion fleet at sea. Consequently, the island was heavily bombed and then shelled by the navy. Finally, on 11 June 1943, British troops landed at the main harbour, and the island garrison surrendered.

During June and July 1943, the Desert Air Force started to relocate to Malta in preparation for the invasion of Sicily.

On 9 July, British, Commonwealth and American troops started landing on Sicily preceded by airborne forces. In the weeks prior to the invasion, the Allies had launched a concerted aerial bombardment of the Axis air forces on Sicily – winning air superiority. However, bad weather on the night of 9 July resulted in the airborne forces being scattered. Once ashore, the British 8th Army initially made steady progress north until checked at Catania. The Americans, under General Patton, took Palermo. After fighting a defensive campaign for about two weeks, the Axis forces started to withdraw. After 38 days, Allied forces finally took Messina. However, around 120,000 enemy troops had been successfully evacuated. At the time, Operation HUSKY was the largest amphibious invasion of the Second World War with over 180,000 men, 4,000 aircraft, and 3,000 vessels deployed.1

Italy 1943

19 – 20 July: Moved by tank landing craft to Sicily. Arrived Pachino beach (southern tip of Sicily) at 06.00hrs.

12 August: Jerry bombed Lentini Drome (south of Catania) during the night (surprise raid) 24 kites were written off, and 96 airmen were killed or wounded (322 Wing).

13 August: Jerry retreats toward Messina evacuating troops.

17 August: Messina reported taken.

18 August: End of Sicilian Campaign.

27 August: Moved to Gerbibi near Mount Etna (west of Catania).

7 September: Arrived Falcone (north coast of Sicily).

Operation AVALANCHE – Allied landings at Salerno, 8/9 September 1943

German forces correctly anticipated the Allied landings near the port of Salerno by the U.S. 5th Army and concentrated five divisions against the beachhead. Initially, it appeared the Allies might be thrown back into the sea. However, Allied airpower gradually strangled the Germans' ability to resupply its land forces, and gradually they had to give ground. However, the Germans exploited the mountainous terrain to their full advantage as they staged a fighting withdrawal northward. Eventually, Allied progress was brought to a halt along the heavily fortified ‘Gustav Line’.

8 September: We were told landings would be made near Naples during the night (Operation AVALANCHE). Ready to move to Naples. Italy surrendered and Naples invaded in the early hours.

During the next few days, the Squadron flew numerous sorties over the beachhead providing air support to the ground forces.

23 September: Moved to Milazzio (west of Messina) and boarded transport, moved off at 20.30hrs headed for the Italian mainland.

24 September: Convoy shelled. Landed midday near Salerno.

28 September: Moved to Battipaglia drome (east of Salerno).

11 October: Moved to Naples passing through Pompei.

30 October: Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park landed at Drome. Note: Park played a pivotal role in winning the Battle of Britain.

Usually, a Spitfire Squadron had twelve aircraft split into two flights of six (A and B Flights). In combat, the aircraft would typically divide into smaller groups of two or three aircraft.

12 November: German fighter bombers attacked a nearby airfield. The Squadron’s aircraft were scrambled and pursued the enemy aircraft, but they escaped.

14 November: 324 Wing broke the record for the number of kites shot down in 12 months: 301.5.

22 November: Enemy aircraft strafed the main road to Rome. Six enemy aircraft were shot down and another six were probably downed.

24 November: Six aircraft on shipping patrol and ‘L’ on patrol of the front line (presume that the letter ‘L’ refers to an individual aircraft).

26 November: A German Ju-88 (The Junkers Ju-88 twin-engine multirole combat aircraft) was shot down by 435 Squadron. Kites on mine sweeping patrol. Enemy aircraft over our drome and heavy AA fire (anti-aircraft artillery sometimes referred to by the British and Commonwealth forces as Ack-Ack).

28 November: Strafed road transport – four trucks and two staff cars hit. F/O (Flying Officer - a junior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force) Swain dived too low, hit some trees, and then went straight into the ground.

2 December: Kites on bomb line patrol. Note: The bomb line is a line or limit beyond which aircraft may make attacks on the enemy without risking damage to their own troops.

5 December: Kit bags lost at BARI (Bari is a port city on the Adriatic Sea and the capital of southern Italy’s Puglia region). 12 ships sunk in the harbour. Souvenirs, etc. all lost, and 500 Woodbines (British brand of cigarettes).

7 December: Red Herbert shot down a Me-109, his first kill. Note: The Messerschmitt Bf 109 was the backbone of the Luftwaffe’s fighter force along with the Focke-Wulf Fw-190. Me-109 and Bf-109 are used interchangeably to refer to the aircraft.

10 December: Jet tanks fitted. Note: I am assuming this diary entry refers to the ground crew fitting jettisonable extra fuel tanks to the Spitfires. These fuel tanks extended the range a Spitfire could fly but also somewhat limited the aircraft’s performance. The fuel tanks were fitted under the central section of the fuselage and carried a 30, 45 or 90-gallon capacity. They were also known as drop tanks or ‘slipper’ tanks and could be jettisoned after use or before engaging enemy aircraft.

16 December: FLT (Flight Lieutenant) Taylor was shot down and belly-landed on a beach. Returned safely the next day.

Christmas: Dick seems to have enjoyed the Christmas period with plenty to eat and drink. He complained of feeling hungover on Christmas day after too much merry-making the night before.

The weather during the late autumn and early winter of 1943/44 steadily deteriorated. The Squadron was often at half-hour readiness (held ready to scramble into action if required). When not working, Dick appears to have spent much of his free time visiting local towns, going to the cinema and the occasional concert, and following the inter-squadron football matches. He was also assigned to sentry duty.

Italy 1944

11 January: Typhus is very bad in Naples.

13 January: Bombers over all day (Flying Fortresses) about 950 passed overhead on their way to bomb Cassino (Between 17 January and 18 May, Monte Cassino and the Gustav Line defences were attacked on four occasions by Allied troops.). All fives went away replaced by nines. Note: Dick is referring to the replacement of Mk. V Spitfires with the new Mk. IX variant.

14-16 January: Prepared to move to a new location. Left Naples at 10.30hrs and arrived at the new drome about 14.00hrs. Crossed the Volturno River Bridge.

18 January: Watched Bostons drop their loads on enemy positions and return safely. In this diary entry, Dick is referring to the American-built Douglas A-20 Havoc medium bomber that was renamed the Boston by the RAF.

19 January: 15 miles behind front lines – guns firing.

Operation SHINGLE, the Battle of Anzio, 22 January – 5 June 1944

To break the deadlock and get the Allied advance moving again, the High Command decided to launch another amphibious landing. The intention of Operation SHINGLE was to bypass the Gustav Line, forcing the Germans to pull troops back from Cassino and open the road to Rome. Operation SHINGLE was launched on 22 January 1944. Initially, the landings were unopposed. However, the Allies quickly lost the initiative and failed to break out from the beachhead. Instead, by 25 January, the Germans counterattacked with elements of five divisions and quickly surrounded the Allied landing force. For months, the Anzio campaign dragged on with neither side able to gain a significant advantage. Eventually, the deadlock was broken when the Allies launched a series of new operations compelling the Germans to redeploy their limited forces. On 4/5 June, Rome fell, but the Germans remained undefeated and pulled back to a new defensive position known as the Gothic Line.2

21 January: Told that another landing would be made 50 miles north of here during the night at Cape ANZIO.

22 January: Landings successful – no opposition. Went to the village of Mondragone (situated on the coast about 28 miles northwest of Naples). The village had been badly bombed.

27 January: The Squadron fetched four down and two damaged for the loss of one pilot missing. Dick often uses the term ‘fetched down’ in his diaries to indicate that the Squadron had either shot down or damaged enemy aircraft.

28 January: The Squadron is down to six serviceable aircraft due to prangs. Plenty of shelling night and day. Note: The loss of aircraft due to non-operational accidents seemed common at the time. Between 1939 and 1945 RAF Bomber Command, for example, lost 1,380 aircraft within the UK on operational flights and 3,986 aircraft in non-operational accidents.

7 February: Two MEs (Messerschmitt Bf 109s) shot down. Red Herbert forced landing with serious injuries.

10 February: Cruisers shelling enemy positions night and day.

12 February: Jerry active over ANZIO beach, bombing and strafing.

15 February: Red Herbert died in hospital. Note: In fact, Flight Sergeant Henry Ivor (Red) Herbert, Service Number: 415189, 93 Sqdn., Royal New Zealand Air Force, died on 7 February 1944, age 20. Red is buried at the Anzio War Cemetery. He had been flying Spitfire Mk. IX MA509.

16-17 February: Dick says the Wing shot down seven enemy aircraft over the ANZIO beachhead. He also writes that ‘R’ and ‘Z’ both had forced landings at ANZIO. I am assuming that Dick is referring to individual aircraft using the RAF letter code. The RAF used three-letter codes to identify aircraft from a distance. Two letters before the roundel, for the squadron to which the aircraft belonged, and another letter after the roundel for the individual aircraft.

1 March: Record of enemy kites destroyed 343.5.

16 March: Cassino was heavily bombed for two days.

18 March: Went on a day trip to Napoli (Naples). Returning at night saw Mount Vesuvius in eruption. Most wonderful sight to see. Hot lava running down the sides. Still visible at 30 miles. The volcanic eruption had started the day before and lasted for about ten days.

22 March: Mount Vesuvius – People have started to evacuate southern Naples.

23 March: Finished work at 17.00hrs and went on a trip to see Mount Vesuvius at night. A sight worth seeing.

24 March: W/O (Warrant Officer) Bunting fetched two MEs down and then force-landed at ANZIO. He returned to our drome flying a Kitty-Hawk. Note: The RAF continued to operate Kittyhawks in Italy until the summer of 1944 when they were finally replaced with North American Mustangs.

30 March: The Squadron's total: 52.5 enemy aircraft shot down, 18 probably shot down, 72.5 damaged.

Between April and mid-May 1944, the Squadron flew numerous sorties over the ANZIO beachhead. Enemy air activity appears to have tailed off with only occasional dogfights. However, pilots and aircraft were still lost, but more due to accidents than enemy action. Dick seems to have spent most of his time as a duty armourer. In his spare time, Dick visited Naples, went to the cinema and went swimming in the sea as the weather steadily improved.

19 May: Cassino and Monastery Hill taken. Plenty of bombers flying north during the day.

21 May: Squadron fetched eight Jerries down.

23 May: Offensive started at ANZIO. Squadron ready to move up.

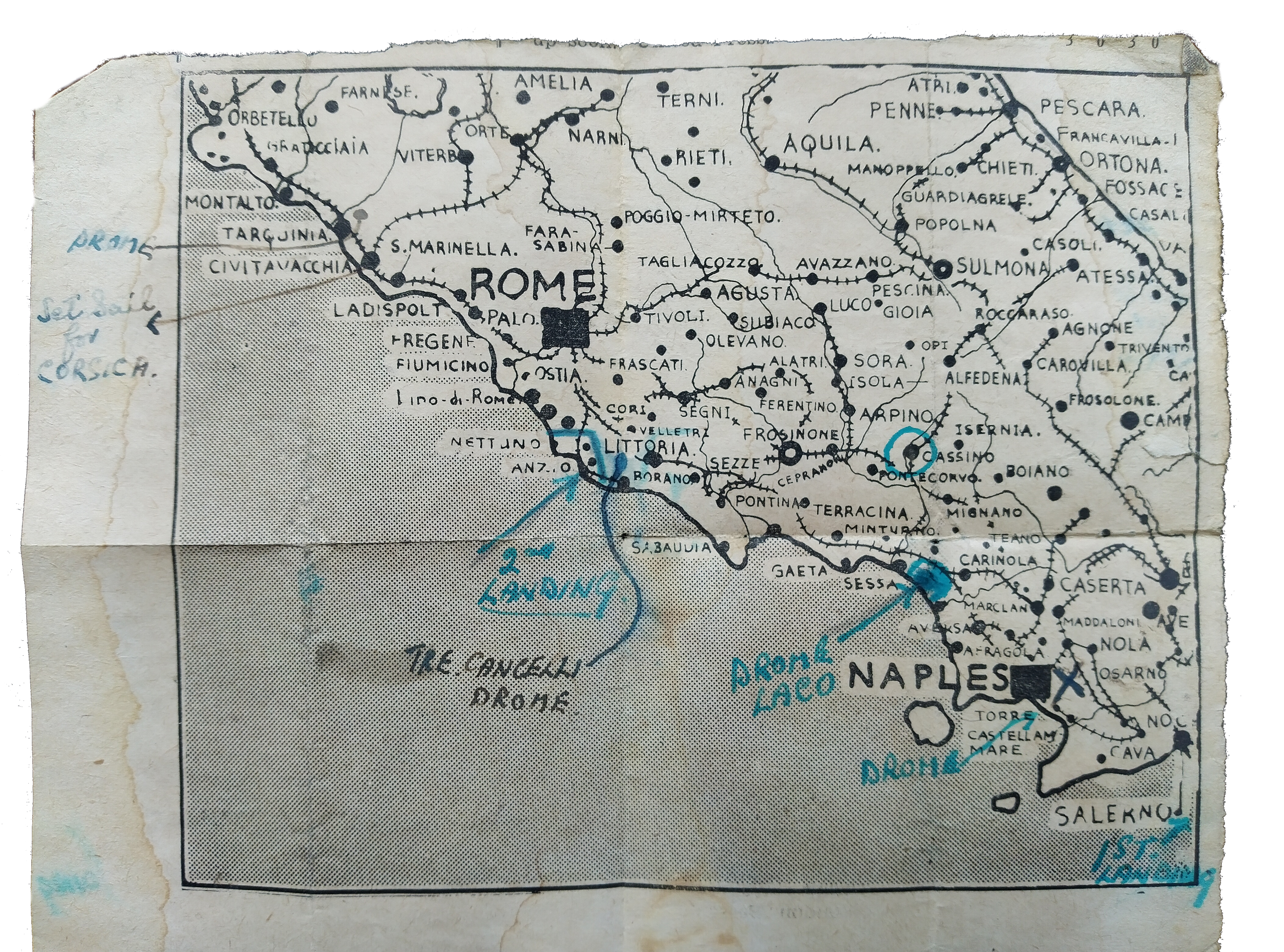

3 June: ‘A’ Party packed lorries. ‘B’ Party took over Squadron kites. ‘A’ Party left camp at 19.00hrs for a drome 96 miles north.

6 June: Started to pitch camp. Heard that the Second Front has started. Rome taken. The liberation of Rome was completely overshadowed by the Normandy landings of D-Day (Operation OVERLORD).

7 June: 05.00hrs woken by anti-aircraft fire. Jerry over our drome.

8 June: Transferred to No. 8 C.C.S. (Casualty Clearing Station) six miles north of ANZIO to an airstrip called Tre Cancelli.

12 June: Packed trucks ready to move at night. Plenty of wrecked tanks on the road and bridges blown up.

13 June: 93 miles north of Rome arrived at Tarquinia (the town is situated on the coast, northwest of Rome) airfield at 03.00hrs. Passed through Rome at midnight. Wonderful buildings. Stayed about an hour in the city.

17 June: Dakotas landing all day to take away the wounded. Note: The Douglas C47 Dakota is one of the most successful military transport aircraft designs in history and was widely used by the Allies during World War Two.

22 June: Left No. 8 C.C.S. for Rome – had a tour of the city.

24 June: Moved about 60 miles north and arrived at Grosseto (another town close to the coast, northwest of Rome). The town was bomb-damaged. The R.E. (Royal Engineers) worked to repair the bomb-cratered landing strip.

4 July: Moved 50 miles north to a new airstrip. It appears from Dick’s diary that enemy air activity had dropped off considerably.

15 July: Moved about 110 miles, south to the docks.

17 July: Left harbour at 19.00hrs heading west, nine LSTs in convoy. Note: The LST or Landing Ship, Tank, was designed to carry around 18 Sherman tanks or 30 3-ton trucks and birth 200 troops. The ship could land vehicles, troops and cargo directly onto beaches without the need for a harbour.

18 July: Arrived Porto Vecchio, Corsica, at 11.00hrs. Headed north along the coast road, stopped overnight at Bastia (northern tip of Corsica).

19 July: Arrived at drome near Calvi (west of Bastia, on the coast) at 17.00hrs.

26 July: Went into Calvi in the evening and sold 200 cigarettes for 30/- (30 shillings) – a good price. You can sell almost anything here at a good price.

27 July: Getting ready for the invasion of southern France (Operation DRAGOON). 90-gallon (drop) tanks fitted to the aircraft. Pilots doing night flying and early mornings. Just the same as in Malta.

30 July – 2 August: Fighters sweep over Genoa and north.

3 August: 93 and 72 Squadrons do sweeps over Nice.

7 August: 43 Squadron pilot burned to death after belly landing and jet tank caught fire. A pilot from 225 Squadron drowned after nose-diving into Calvi Bay.

11 August: The whole Wing went on a strafing raid at 18.00hrs. They wrecked a lot of radio location stations around Nice. The mission was a complete success.

Operation DRAGOON, Invasion of southern France, 15 August – 14 September 1944

Operation DRAGOON (originally codenamed ANVIL) was an Allied invasion of southern France that led to the drive up the Rhone River Valley. Originally intended to support the D-Day invasion and Operation Overlord, DRAGOON was carried out more than two months later because of a lack of supplies and equipment. Within days, the Allies secured more than 40 miles of coastline and captured the vital French ports of Toulon and Marseille, providing critical support to the Normandy-based Allied forces moving to the German border. DRAGOON was largely an American and French operation, however, 324 Wing, including 93 Squadron provided part of the air umbrella.3

15 August: Invasion took place (start of Operation DRAGOON). Two gliders landed at the drome. A Fortress (Flying Fortress) landed shot-up by flak (A contraction of the German Flugabwehrkanone meaning anti-aircraft artillery). Kites doing air cover over the invasion beaches from dawn to dusk, but no Jerries to be seen.

21 August: Moved off for docks at 09.00hrs. Boarded LST at L'Île-Rousse (Corsica) and pulled out of the harbour at 20.00hrs. Very rough sea, the ship was rolling and pitching.

22 August: Arrived at Cavalaire (Cavalaire-sur-Mer is southwest of Nice between Saint-Tropez and Toulon in the southeast region of France) at 20.00hrs. Slept at a marshalling area outside of the town.

23 August: Left at 09.00hrs for a drome 15 miles away at St. Tropez and arrived at 11.30hrs. Departed again at 15.30hrs for a drome 140 miles north.

24 August. Terrible accident on the way down a mountain, and two died. Arrived at Cisteron (sic. Sisteron) at 20.00hrs. Marseille and Bordeaux regions of France were liberated by the Allies.

27 August – 1 September: The Squadron flew strafing sorties against enemy transport, shooting up trains, trucks, cars, etc. During this period several pilots and aircraft were lost.

5 September: Moved about 115 miles toward Lyon.

6 September: Left camp at 08.00hrs. Passed through Vienne (south of Lyon). We saw hundreds of Jerry transports burnt out along the road. Rhône valley. Arrived at Lyon airport at 16.00hrs.

8 September: The Squadron flew sweeps over Germany – strafed Jerry trucks. ‘M’ shot down in flames. F/SGT Wagstaffe killed. Flight Sergeant John William Wagstaffe, service No. 1430722, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, 93 Squadron, was killed in action flying Spitfire Mk IX MH324. He is buried in Bessey-La-Cour Churchyard, France.

22 September: Moved back to Lyon, 150 miles.

28 September: Passed through Avignon, France, and arrived at La Jass (sic. La Jasse) at 15.00hrs. Travelled 160 miles.

3 October: Moved to Marseille. Arrived at the staging area at 16.00hrs.

5 October: Boarded LST at 05.00hrs.

6 October: The boat moved out at 11.30hrs in a heavy thunderstorm. The boat was like a rocking horse.

7 October: Passed between Corsica and Sardinia at noon. Turned north for Leghorn. Note: Livorno, Italy, also known as Leghorn, which derives from the Genoese name Ligorna.

8 October: Disembarked at 18.00hrs.

During October and November, the weather in Italy steadily worsened with the airstrips often flooded, making them unserviceable (US). As no sorties could be flown for days at a time, Dick spent his time watching films and doing sentry duty.

17 – 18 November: Travelled by lorry 112 miles to Via Figliano (north of Florence) and then another 120 miles to Rimini.

20 November: Fitting bombs on the aircraft. They successfully bombed a railway.

Italy 1945

For the remainder of November, December and into January 1945, No. 93 Squadron flew interdiction missions, bombing and strafing enemy positions, infrastructure, and transport targets. Dick spent his time re-arming the Squadrons’ Spitfires. The winter weather would pause flying for days at a time. The Squadron continued to lose aircraft and pilots to enemy action and accidents.

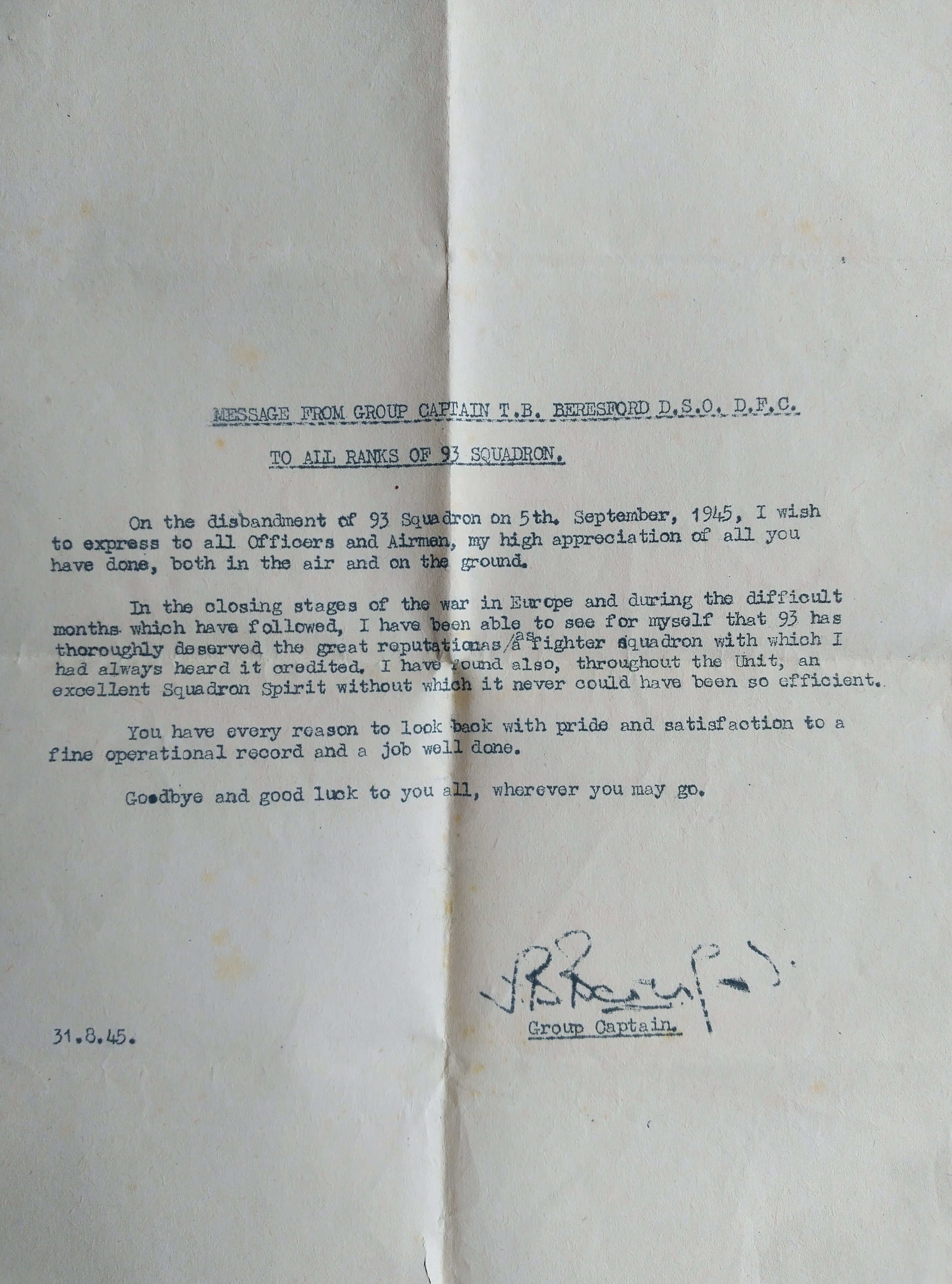

During the early months of 1945, No. 93 Squadron mainly flew interdiction missions in support of ground operations to defeat the last pockets of German resistance in the north of Italy. On 2 May 1945, the Germans surrendered in Italy to Field Marshal Harold Alexander. On 4 May, all German forces in northwest Europe submitted to Field Marshal Montgomery. On 8 May, Victory in Europe (VE Day) was declared.

The air war in Italy cost the Allied Air Forces around 8,000 aircraft and 12,000 service personnel. They had flown 865,000 sorties and in the last seven months of the campaign had dropped around half a million tons of bombs. Immediately after VE Day, 93 Squadron moved to Klagenfurt, Austria on 15 May. On 5 September 1945, the Squadron was disbanded.

Sources:

The personal papers and diaries of Dick Hewitt, No. 93 Squadron, RAF.

Books

Evans, Bryn, The Decisive Campaigns of the Desert Air Force 1942-1945 (Pen & Sword, 2014), eBook.

Farish, Greggs, McCaul, Michael, Algiers to Anzio with 72 & 111 Squadrons (Woodfield Publishing, 2002).

Rawlings, John, Fighter Squadrons of the R.A.F. and Their Aircraft (Crecy Publishing, 1992).

Websites

1. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/01/a2055601.shtml

3. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/operation-husky

4. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/anzio-the-invasion-that-almost-failed

5. https://wikisummaries.org/operation-dragoon/

6. https://www.jeversteamlaundry.org/93squadhistory2.htm

7. https://www.keymilitary.com/article/prejudice-good-order

8. http://www.rafcommands.com/database/serials/details.php?uniq=MH324