The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We would like to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. And we look at the history of unique World War Two artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

Living on Borrowed Time, the Story of Captain John Hannaford

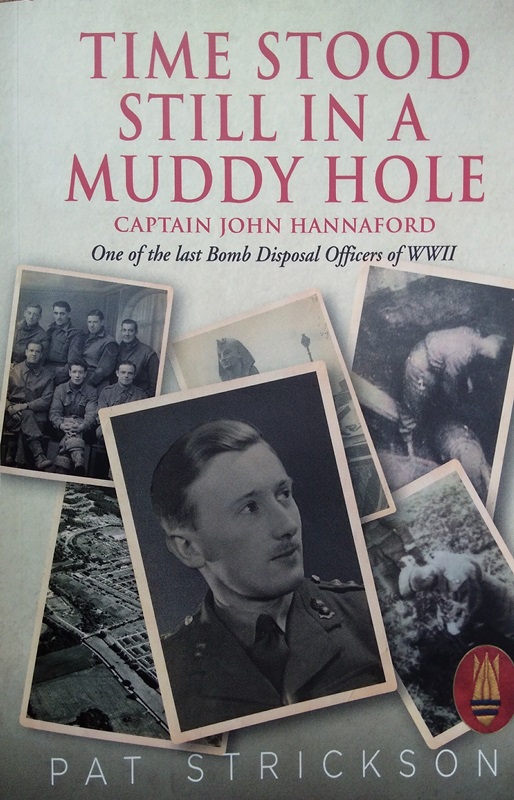

In her book Time Stood Still in a Muddy Hole, first-time author Pat Strickson tells the fascinating true story of Captain John Hannaford, one of the UK’s last Bomb Disposal officers of World War Two. Read the full book review now on The War Years.

As a boy, I loved to watch actor Anthony Andrews play Lieutenant Brian Ash in the TV series Danger UXB. The show revolved around the daring exploits of a young Royal Engineers officer posted to a Bomb Disposal unit during the London Blitz. In reality, over 50,000 bombs were successfully defused during World War Two for the loss of 580 men and one woman killed while serving with the Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal. A dirty, nerve-racking and incredibly dangerous job that required a special type of courage. However, a job that was never officially recognised after the war.

In her book Time Stood Still in a Muddy Hole, first-time author Pat Strickson tells the fascinating true story of Captain John Hannaford, one of the UK’s last Bomb Disposal officers of World War Two. In fact, Pat’s book is really two stories. One is about the life and career of one Avro Frederick John Hannaford. Personally, I think it’s a great name, but John never appreciated it. His father was a World War One pilot and named him after the Avro aircraft company. The second, parallel story is Pat’s own journey to becoming a historical researcher, author and custodian of John’s legacy.

It was only towards the end of his life that John started to talk about his wartime experiences. Luckily, once he started he couldn’t stop. He was interviewed for a Channel 4 documentary series by the Imperial War Museum as well as local press. Sadly, he died on Armistice Day 2015, aged 98, without ever meeting his biographer. A year later, Pat came across a watercolour of a Bexhill landmark in a local charity shop. Her desire to learn more about the artist would lead to years of painstaking research and countless hours in front of the computer. I think the end result was worth the effort.

John’s early career as an apprentice architect working at the Royal Ordnance Factory Chorley made him an ideal candidate for officer training in Bomb Disposal. Once qualified, John’s life expectancy was just ten weeks. The physical rigours of the job and the constant threat of being vaporised created a unique camaraderie between John and his men. Nevertheless, after two years the stress of the job gave him a duodenal ulcer, which probably saved his life. The men of John’s section were not so fortunate. When tragedy struck, it wasn’t due to enemy action. However misplaced the sense of guilt, John never quite forgave himself for not being there. After the war, he would marry; raise a family and go on to have a successful career as an architect. But the war cast a long shadow.

John was a much-loved and respected member of his community. That knowledge must have placed the weight of expectation squarely on Pat Strickson’s shoulders. So telling his story faithfully required tact, sensitivity and honesty from the author. Pat’s use of the literary technique known as a frame story works well, essentially telling John’s story by telling her own. Overall, the book is well-researched, engaging and informative. I also found it shocking and laugh-out-loud funny at turns. I always think it’s hard to criticise the quality of a biography, after all, who really knows anyone? But the book feels authentic. However, I did find one factual inaccuracy. John’s wife Joyce had been married and widowed. Her first husband was killed during the fighting at Arnhem in 1944. Arnhem is in Holland, not Belgium.

Like so many wartime veterans, John remained haunted by his experiences and yearned to see his comrades properly recognised for their courage, devotion to duty and sacrifice. Pat Strickson’s book certainly goes some way to balancing the scales.

The Miracle of Dunkirk Retold

In this blog post, we take a look at Christopher Nolan’s new war movie, Dunkirk.

The historical, technical and military inaccuracies aside, Christopher Nolan’s new war movie Dunkirk is worth the price of the ticket. It’s a big movie, beautifully shot on location, that tells the story of the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from three different perspectives: land, sea and air. However, the epic scale of the film, and Chris Nolan’s preference to use real men, ships and planes over CGI wherever possible, often left the screen strangely underpopulated. Operation Dynamo might have been something of a military and logistical miracle, having rescued around 340,000 men between May 26th and June 4th, 1940, instead of the original estimate of just 35,000. Nevertheless, Dunkirk was a major defeat, and no amount of propaganda about the armada of little ships could hide the fact.

Spitfires

Dunkirk features a great cast including Harry Styles, Tom Hardy, Cillian Murphy, Mark Rylance, Fionn Whitehead and Kenneth Branagh. I think Nolan has to be applauded for his all-Brit and Irish cast. I’m sure the studio’s money, marketing and PR people would have been screaming for a Hollywood A-lister to give the film more box-office appeal across the Atlantic. I think Fionn Whitehead did a very credible job as the central character, and possibly the unluckiest Tommy to put on a uniform. Of course, the real stars of the movie were the three Supermarine Spitfires (two Mk.Ia’s and an Mk.Vb according to Warbird News) and the Hispano Buchon doing a credible job of playing a Messerschmitt Bf 109E. I think I’ve seen all of these planes at shows like Flying Legends in recent years. Duxford’s Bristol Blenheim (the only one still flying) also put in a brief appearance. The movie’s Heinkel He 111 is a large, radio-controlled model.

CGI

To my mind, Chris Nolan missed a trick, not embracing and integrating CGI with live-action and genuine kit for Dunkirk. I think Director Joe Wright did a much better, in fact, an extraordinary job with his continuous, five-minute tracking shot of the Dunkirk beach in Atonement (2007). In this one scene, Wright successfully conveys a much more believable account of the chaos, absurdity and tragedy of the retreat and evacuation. We see masses of dishevelled men, wrecked and burning vehicles, a French officer shooting horses, soldiers singing and playing football while others drink, and above it all, the sky is black with thick, oily smoke. Of course, all the CGI in the world won’t save a badly written, acted and directed piece of nonsense such as Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge (2016). Like just about everything else in the film, the CGI is used with no skill or finesse, so looks fake and totally unbelievable.

Miracle of Dunkirk

Films like Hacksaw Ridge take amazing true stories of courage and sacrifice and turn them into shameful pantomimes. In contrast, Christopher Nolan uses the historical events of May/June 1940 as the stage for a story of courage, hope and redemption. Dunkirk might not be technically or historically quite on the money, and I’m sure Tom Hardy knows you’d be lucky to walk away alive if you really tried to land a Spitfire like that, but then it isn’t a documentary. To me, Chris Nolan’s film is both a question and a reminder. What would we do with our backs against the wall and defeat starring us in the face? Once upon a time, our parents and grandparents faced an implacable enemy, refused to surrender, and turned defeat into victory – maybe then and now that is the miracle of Dunkirk.

The Abbeville Boys, Focke Wulf Fw-190A1

In this blog, we take a look at the unique history of a piece of the engine cowling from Fw-190A-1 Wn.10036. The Fw-190 was part of Jagdgeschwader (JG) 26 "Schlageter" known to the Allies as "The Abbeville Boys". Piloted by Oberfeldwebel Helmut Ufer, the Fw-190 was shot down by an RAF Spitfire in July 1942.

Visiting Flying Legends 2017 WW2 warbirds airshow at IWM Duxford, I happened upon a piece of Focke-Wulf Fw-190 engine cowling. Designed by Kurt Tank in the late 1930s and widely used by the German Luftwaffe during World War II, the Fw-190 Würger (Shrike in English) quickly established itself as a fearsome multi-role aircraft. Until the introduction of the improved Spitfire Mk. IX towards the end of 1942, the RAF didn’t have a comparable interceptor at low and medium altitudes. Named after the Shrike, a small carnivorous bird of prey known for impaling its prey on spikes, the Fw-190 was nicknamed the “butcher bird”.

My particular piece of butcher bird came from Fw-190A-1 Wn.10036. The Fw-190A-1 was in production from June 1941. It was powered by the BMW 801 C-1 engine, rated at 1,560 PS (1,539 hp, 1,147 kW) for take-off. Armament included two fuselage-mounted 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s and two wings root-mounted 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s (in all four MG 17s synchronized to fire through the propeller arc) and two outboard wing-mounted 20 mm cannons.

On the afternoon of Sunday, 13 July 1942 Oberfeldwebel Helmut Ufer was flying at 16,000 feet near the JG26 airfield of Abbeville in France. Ufer, a long-time member of 4/JG26, was flying Fw-190A-1 Wn.10036, designated White 5, only the thirty-sixth production model.

Helmut Ufer had been a tank driver in the Reichwehr. He was released from service in 1935. He volunteered for the Luftwaffe at the start of the war and began his flight training in March 1940. Ufer had won a number of aerial victories. On 13 March 1942, Ufer shot down a Spitfire V over Wirre Effroy northeast of Boulogne. The Spitfire belonged to 124 (Baroda) Squadron, RAF, based at Debden. The pilot was Michael Gordon Meston Reid, 116060, who subsequently died of his wounds at a German Naval Hospital on 7th August 1942. Pilot Officer Reid’s grave is one of four commonwealth war graves and one Polish to be found in Hardinghen cemetery, northeast of where he was originally shot down. On 4 April 1942, Ufer shot down one of 11 Spitfires claimed by JG26 over St. Omer. He downed another Spitfire from 222 Squadron at St. Valery-sur-Somme on 30 April 1942.

Jagdgeschwader (JG) 26 "Schlageter" was known to the Allies as "The Abbeville Boys". The unit crest of a black gothic 'S' on a white shield was created to reflect its involvement in the re-occupation of the Rhineland on March 7, 1936. 4./JG26 belonged to the second Gruppe within the Jagdgeschwader 26 (II./JG26). Karl Ebbighausen then selected a caricature of a tiger's head to represent the unit and it was painted onto each 4.Staffel aeroplane with pride.

On that Sunday afternoon, a group of Spitfires from 616 Squadron led by Australian Flight Lieutenant F.A.O. Tony Gaze were on a 'Circus' to Abbeville. Tony flew with the 616 Squadron until 29 August 1942, by which time he had destroyed 4 enemy planes and one probable.

Tony Gaze finished the war a double-Ace with 11 destroys and 3 shared, including a Me262 and Arado 234, 4 probables and one V1. He was the first Australian to destroy an enemy jet in combat and the first Australian to fly a jet in combat. He has the rare distinction of being awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross three times (DFC with 2 bars) which only 48 people have received in its history. He later went on to have a career in motor racing.

Gaze later reported:

“After a right-hand orbit around Abbeville at 21,000 feet, I saw a single Fw-190 climbing up at about 16,000 feet between us and the coast. I made sure nothing was above us and led Red Section down to attack. I fired a one-second burst from around 300 yards from astern above seeing cannon strikes on the port main plane near the cockpit. As I started to fire again the '190 flicked to the left emitting a puff of black and white smoke and spun down.”

Several other pilots reported seeing the Fw-190 carry on spinning down, apparently out of control, until they lost sight of it. It must be assumed that Oberfeldwebel Helmut Ufer was killed by Gaze's fire after being caught unawares from behind.

On the ground, the villagers of Nibas, to the southwest of Abbeville, were on their way to mass in the village church. Alerted by the howl of an aircraft engine, some caught sight of it diving, almost vertically, towards them. With a huge explosion, the aircraft crashed into a field about 300 yards away from the church. There was little to be found of the aircraft. A smoking crater and a few fragments of metal were all that was left of Ufer's Fw-190.

The Luftwaffe later recovered Ufer’s body and noted the crash site.

Simon Parry of Aviation Archaeology explains, “The owner of the field, grandson of the war-time owner, was kind enough to point out the location of the Fw-190 crash and allowed a team to excavate what was left of the plane. At length, the BMW801 engine, tail wheel, parts of the armament and other items were recovered from a depth of up to 15 feet.”

Sources: Wikipedia on Fw-190, JG26

The German War: Crimes and Persecution Complex

The German War by Nicholas Stargardt and The Bitter Taste of Victory by Lara Feigel are two WW2 history books that neatly dovetail one another. The German War examines the many, varied aspects of the German war experience from 1939 to 1945 at home and on the frontlines. The Bitter Taste of Victory begins in 1944 as Allied forces, East and West, advance into the shrinking Reich and extends to 1949.

The German War by Nicholas Stargardt and The Bitter Taste of Victory by Lara Feigel are two history books that neatly dovetail with one another. The German War examines the many, varied aspects of the German war experience from 1939 to 1945 at home and on the frontlines. The Bitter Taste of Victory begins in 1944 as Allied forces, East and West, advance into the shrinking Reich and extends to 1949. Both books focus heavily on the question of German guilt for the many crimes committed under the Nazi regime, remorse and reconstruction. Chillingly, each book comes to the same conclusion: the only thing the surviving Germans truly felt guilty about was losing the war. The only pity most Germans felt was self-pity. Her cities, centres of industry and infrastructure lay in ruins. Millions were displaced and homeless. Hunger, disease, and lack of winter fuel all contributed to the misery after the nation’s collapse. However, for the victims of the camps, the millions of slave labourers, and all those countries ravaged by the German war machine there was no thought, no compassion and no sense of national guilt or shame. On the contrary, population surveys taken 5 and 10 years after the war revealed German sentiment towards the Jews and many Nazi policies had barely changed for many.

The German War examines the many motivating factors that kept the German people fighting right until the bitter end, even when defeat was assured. It reveals how most Germans initially believed they were fighting a war of national defence against Poland, France and Great Britain. Later, the Allied air offensive convinced many Germans of their victimhood, although some saw it as a punishment for their crimes against the Jews. The book also exposes the lie that most Germans were ignorant of the many atrocities committed by the regime. In fact, right from the start of the conflict German soldiers were documenting their crimes in writing, photography and film. But perhaps one of the darkest aspects of the book is just how quickly ordinary men and women could be transformed from law-abiding citizens to brutal murderers and rapists. The transformation often took less than two months. In Russia, senior field commanders began to worry about their troop’s propensity to loot property, burn villages and slaughter the inhabitants without orders. When defeat and occupation finally came to the German nation it did nothing to change outlooks and attitudes. Even years after the war’s end, the majority of Germans believed that Nazism had essentially been a good idea, poorly executed.

Lara Feigel’s book The Bitter Taste of Victory begins in the closing months of the war, as reporters, writers, filmmakers and entertainers followed the advancing Allied armies into the heart of Nazi Germany. The book illustrates the utter destruction wrought on German cities by the Allied bombing campaign and contrasts it with the horrors of death and concentration camps such as Bergen-Belsen. Martha Gellhorn, Marlene Dietrich, Billy Wilder and George Orwell are just some of the famous names we encounter amidst the rubble and misery of Germany’s defeat. With incredible naivety, the occupying powers set about a process of denazification. Writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers were recruited to cleanse German culture of its Faustian excesses. However, German re-education, the Nuremberg Trials and occupation seem to have done nothing to change the population’s psyche. Instead, the realpolitik of the Cold War allowed former Nazis and war criminals to reinvent themselves without actually changing. Rather than accept any collective guilt, the Germans of the war period were satisfied to largely remain silent or seek refuge in empty platitudes and point the finger of blame anywhere but at themselves. There is some small irony that far-left-wing groups such as the Baader-Meinhof Gang would later regard the West German state as the continuation of fascism and imperialism by other means.

In reality, these two books arrive at the same stark conclusion, although starting from very different places. The Germans of the war years remained fixed in their beliefs that they were victims, not perpetrators. They largely believed Nazism was correct in its outlook, but poorly executed by the regime. That brutality, murder, and even genocide were justifiable in pursuit of national goals. These two books also illustrate just how quickly the most civilised and educated of people can be transformed into remorseless killers, happy to abdicate all responsibility for their crimes.