The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We would like to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. And we look at the history of unique World War Two artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

Diplomats & Admirals: The Origins of the Pacific War

In this military history book review, I examine 'Diplomats & Admirals' by Dale A. Jenkins - a fascinating look at how diplomatic failures led to Pearl Harbour and the Pacific War. Jenkins, a former US Navy officer, reveals how close Japan and America came to avoiding conflict in 1941. His analysis shows how personal ambition, institutional rigidity and communication failures among key figures on both sides derailed opportunities for peace. Despite having the world’s most powerful navy in 1941, Japan's leadership understood that a war with America would likely result in defeat.

Diplomats & Admirals by Dale A. Jenkins (Aubrey Publishing Co., New York, 2022) offers a fresh perspective on one of the most studied periods of World War Two, focusing particularly on the diplomatic manoeuvring that preceded the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States. Jenkins, a former U.S. Navy officer with extensive experience in the Pacific region and later careers in international banking and Council on Foreign Relations, brings both military and diplomatic insights to this compelling story.

The book’s greatest strength lies in its detailed examination of the diplomatic efforts to prevent war in the Pacific. Jenkins meticulously documents the complex web of personalities, policies, and missed opportunities that ultimately led to conflict. His portrayal of key figures such as Japan’s Prince Konoe, Foreign Minister Matsuoka, and US Secretary of State Cordell Hull reveals how personal ambition and rigid thinking often trumped rational diplomacy. Particularly telling is his description of Matsuoka, who “was interested, not in promoting the interests of Japan, but rather those of Matsuoka Yosuke,” and who was willing to “gamble the future of Japan and its seventy-seven million people” for his own political advancement.

Jenkins presents several fascinating “what-if” scenarios where war might have been avoided. One particularly striking example involves the Dutch East Indies oil negotiations, where Jenkins suggests that “willingness to allow a modest flow of oil could have precluded the Japanese invasions” and potentially removed the threat of Japanese economic collapse that drove them toward war.

The book’s treatment of the military aspects of the conflict, while competent, covers more familiar ground. However, Jenkins still manages to provide interesting insights, particularly in his analysis of the Japanese naval leadership’s persistent attachment to battleship warfare despite the rising dominance of aircraft carriers in naval engagements. This is notably illustrated in his discussion of Admiral Yamamoto’s planning for the Battle of Midway, where “despite his development of the carrier force, its unprecedented attack on Pearl Harbor (sic), and its victories in the south Pacific and Indian Ocean prior to Midway, Yamamoto compulsively remained a battleship admiral.”

One of the book’s most valuable contributions is its examination of the communication failures between different branches of government and military services. A prime example is Jenkins’ observation that Hull’s diplomatic stonewalling tactics stemmed partly from “the mistaken belief that in a war with Japan US forces would prevail in a few months,” noting that “taking five minutes to talk with Admiral Stark on the power of the Japanese navy never occurred to him.”

The narrative is strengthened by Jenkins’ ability to weave together the personal, political, and military aspects of the story. His background in both naval service and international affairs allows him to provide nuanced analysis of both the diplomatic scheming and military operations.

Today, it is easy to forget that back in 1941, Japan possessed the world’s most powerful navy and some of the most advanced aircraft. As Jenkins notes, the Japanese had developed “carrier operations and armaments that were, at that time, the most advanced in the world,” including the highly manoeuvrable Mitsubishi A6M Zero long range fighter. Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy was struggling with obsolete equipment - Jenkins points out that “in the early months of the war, the US Pacific Fleet was hampered by obsolete torpedo planes and hopelessly ineffective World War I torpedoes.” The fact that American naval forces managed to achieve victory at Midway despite these disadvantages makes their triumph even more remarkable and a testament to the courage of their pilots.

Diplomats & Admirals serves as both a fascinating historical account and a cautionary tale, demonstrating how personal ambition, institutional rigidity and failures of communication can lead nations into unnecessary conflict. Many readers, even those familiar with the Pacific War, might be surprised by Jenkins’ revelations about the missed opportunities for peace and the tragic consequences that followed. This well researched work is a valuable addition to the literature on the Second World War, offering insights into the complex, often murky diplomatic negotiations that preceded a conflict which would ultimately cost 25 million lives.

- END –

Image Attribution:

Wikipedia.org: An Imperial Japanese Navy Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zero” fighter on the aircraft carrier Akagi during the Pearl Harbor attack mission. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Pearl_Harbor#/media/File:A6M2_on_carrier_Akagi_1941.jpeg

Wikipedia.org: Secretary of State Cordell Hull (1887–1955) brought Japanese Ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura (1877–1964, left) and Special Envoy Saburō Kurusu (1886–1954, right) to the White House for a meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) on 17 November 1941. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cordell_Hull#/media/File:Hull,_Nomura_and_Kurusu_on_7_December_1941.jpg

Wikipedia.org: U.S. Navy Torpedo Squadron 6 (VT-6) Douglas TBD-1 Devastator aircraft are prepared for launching aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) at about 0730-0740 hrs, 4 June 1942, Battle of Midway. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Midway#/media/File:Douglas_TBD-1_Devastators_of_VT-6_are_spotted_for_launch_aboard_USS_Enterprise_(CV-6)_on_4_June_1942_(80-G-41686).jpg

World War One Missing Manuscript Returns Home

In this book review we take a look at a lost manuscript of the Great War finally published. Field Dressing by Stretcher Bearer, France 1916 – 1919, is a slim volume of World War One poems by Alick Lewis Ellis. He served as a stretcher bearer with the 2/3rd London Field Ambulance, 54th Division, London Regiment, and took part in the Battle of the Somme, Arras, Ypres and Cambrai.

Field Dressing by Stretcher Bearer, France 1916 – 1919, is a slim volume of World War One poems by Alick Lewis Ellis. He served as a stretcher bearer with the 2/3rd London Field Ambulance, 54th Division, London Regiment, and took part in the Battle of the Somme, Arras, Ypres and Cambrai. During his time on the Western Front, Alick took to writing poetry to capture and make sense of his experiences. His notebook of poems was lost for nearly a hundred years until someone anonymously handed it to Dan Hill at the Herts at War Society in 2017. Dan Hill subsequently tracked down Alick’s remaining family, and together they worked to publish Field Dressing by Stretcher Bearer. To recognise the essential role played by the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) and military mental health charities, a proportion of the book’s profits will go to Combat Stress and Veterans With Dogs.

Alick Lewis Ellis appears to have led an unremarkable life. He had a basic education and looked forward to a career as a grocer if the war had not intervened. His war poems might not have the literary complexity and construction of Wilfred Owen, Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon. Nevertheless, they have merit and share many common themes with the famous war poets of his generation. His poems reflect the direct experiences of war. They celebrate their comrades, condemn the war leaders, scorn the indifference of many civilians, and express a longing for home. Unfortunately, we know nothing of Alick’s creative influences or inspirations. The documentary of his life is reduced to a few faded photos, sketchy family memories and military service records.

Regardless of the many horrors and privations of the Western Front, Alick seems to have maintained his sense of humour. In poems like Revenge, he jokes about the quality of Army food, especially the rock-hard biscuits issued to the troops. In Training and Reality, he uses humour to illustrate just how poorly depot life and parade ground drill prepared soldiers for combat. After the war, Alick returned to working in retail, but little else about his life is known. Sadly, he passed away in November 1953. Alick’s poems might not be the greatest literary works, but they are honest, funny and poignant. Regrettably, they tell us familiar stories as old as war itself.

Living on Borrowed Time, the Story of Captain John Hannaford

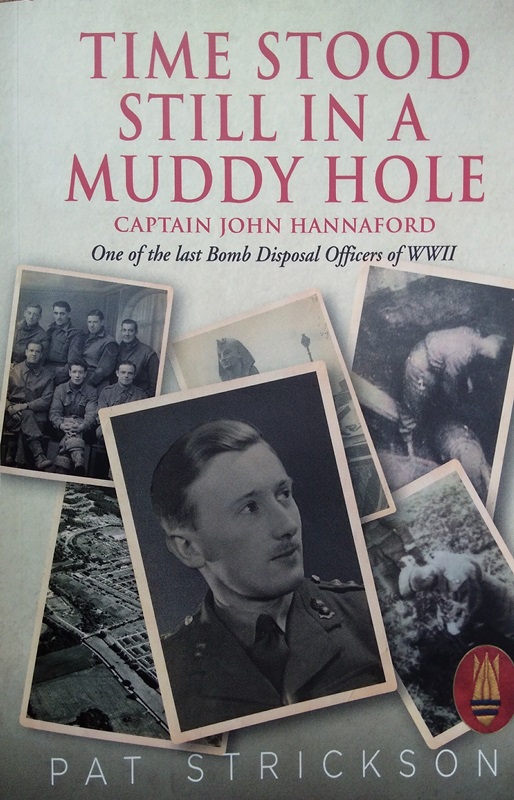

In her book Time Stood Still in a Muddy Hole, first-time author Pat Strickson tells the fascinating true story of Captain John Hannaford, one of the UK’s last Bomb Disposal officers of World War Two. Read the full book review now on The War Years.

As a boy, I loved to watch actor Anthony Andrews play Lieutenant Brian Ash in the TV series Danger UXB. The show revolved around the daring exploits of a young Royal Engineers officer posted to a Bomb Disposal unit during the London Blitz. In reality, over 50,000 bombs were successfully defused during World War Two for the loss of 580 men and one woman killed while serving with the Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal. A dirty, nerve-racking and incredibly dangerous job that required a special type of courage. However, a job that was never officially recognised after the war.

In her book Time Stood Still in a Muddy Hole, first-time author Pat Strickson tells the fascinating true story of Captain John Hannaford, one of the UK’s last Bomb Disposal officers of World War Two. In fact, Pat’s book is really two stories. One is about the life and career of one Avro Frederick John Hannaford. Personally, I think it’s a great name, but John never appreciated it. His father was a World War One pilot and named him after the Avro aircraft company. The second, parallel story is Pat’s own journey to becoming a historical researcher, author and custodian of John’s legacy.

It was only towards the end of his life that John started to talk about his wartime experiences. Luckily, once he started he couldn’t stop. He was interviewed for a Channel 4 documentary series by the Imperial War Museum as well as local press. Sadly, he died on Armistice Day 2015, aged 98, without ever meeting his biographer. A year later, Pat came across a watercolour of a Bexhill landmark in a local charity shop. Her desire to learn more about the artist would lead to years of painstaking research and countless hours in front of the computer. I think the end result was worth the effort.

John’s early career as an apprentice architect working at the Royal Ordnance Factory Chorley made him an ideal candidate for officer training in Bomb Disposal. Once qualified, John’s life expectancy was just ten weeks. The physical rigours of the job and the constant threat of being vaporised created a unique camaraderie between John and his men. Nevertheless, after two years the stress of the job gave him a duodenal ulcer, which probably saved his life. The men of John’s section were not so fortunate. When tragedy struck, it wasn’t due to enemy action. However misplaced the sense of guilt, John never quite forgave himself for not being there. After the war, he would marry; raise a family and go on to have a successful career as an architect. But the war cast a long shadow.

John was a much-loved and respected member of his community. That knowledge must have placed the weight of expectation squarely on Pat Strickson’s shoulders. So telling his story faithfully required tact, sensitivity and honesty from the author. Pat’s use of the literary technique known as a frame story works well, essentially telling John’s story by telling her own. Overall, the book is well-researched, engaging and informative. I also found it shocking and laugh-out-loud funny at turns. I always think it’s hard to criticise the quality of a biography, after all, who really knows anyone? But the book feels authentic. However, I did find one factual inaccuracy. John’s wife Joyce had been married and widowed. Her first husband was killed during the fighting at Arnhem in 1944. Arnhem is in Holland, not Belgium.

Like so many wartime veterans, John remained haunted by his experiences and yearned to see his comrades properly recognised for their courage, devotion to duty and sacrifice. Pat Strickson’s book certainly goes some way to balancing the scales.

Two Books on the Tank War for Northwest Europe

In this double book review, we look at two very different titles that both look at the tank war in Northwest Europe from very different perspectives. Ken Tout's book A Fine Night for Tanks takes an almost forensic look at Operation Totalize. Tank Action by David Render is a very personal portrait of the Allied advance from the Normandy beaches to Germany from the viewpoint of a junior tank commander.

The last year of the war in Northwest Europe was a bloody and protracted affair, especially if you were in an M4 Sherman tank at the cutting edge of the Allied advance. A Fine Night for Tanks, The Road to Falaise, by Ken Tout (originally published in 1998) takes an almost forensic look at Operation Totalize. In stark contrast, Tank Action by David Render with Stuart Tootal, An Armoured Troop Commander’s War 1944-45, recalls the very personal war experiences of a junior British tank officer.

A Fine Night for Tanks, The Road to Falaise

Ken Tout’s book is a detailed study of the various elements of the joint British and Canadian operation to break the German line south of Caen and ultimately help close the Falaise Gap. After a successful night attack using tanks and troops mounted in hastily converted M7 Priest self-propelled gun carriages, nicknamed Kangaroos, the operation stalled. Historically, Operational Totalize has generally been regarded as just another hammer blow against the 1st SS Panzer Corps. Preceding operations such as Epsom, Windsor and Charnwood were bloody battles of attrition costing thousands of men and hundreds of tanks on both sides. However, the difference was the Germans could ill-afford such grievous losses while the Allies had a seemingly endless supply of replacements.

The Death of Wittmann

An interesting footnote to Operation Totalize was the death of German panzer ace, Michael Wittmann. An SS-Hauptsturmführer with the 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion, Wittmann is credited with around 135 tank kills. Although completely unknown to Allied troops during the war, Wittmann has become legendary, especially for his encounter with the British 7th Armoured Division at the Norman town of Villers-Bocage. The circumstances of Wittmann’s death during Operation Totalize have been much debated. Ken Tout tells how Trooper Joe Ekins, 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry, the gunner in a Sherman Firefly, caught Wittmann’s Tiger in the open and fired the fatal shot. I had the pleasure to meet Joe Ekins briefly at Tankfest a few years ago.

While being informative and easy to read, Ken Tout’s book does have a number of factual errors and typos, such as repeatedly referring to a Panther’s 88mm gun when it was armed with a 75mm.

Tank Action

Tank Action by David Render tells his very personal story of fighting across Northwest Europe from the D-Day beaches and infamous bocage countryside to Holland and finally into Germany. Render paints a vivid picture of life as a Troop Commander of an M4 Sherman tank with all its discomforts and many dangers. Render explains the many shortcomings of the standard M4 from its thin armour and high profile to its 75mm gun. The Sherman lacked the penetrating firepower of German 88mm anti-tank guns, Panzerfaust handheld anti-tank weapons and most types of panzer. However, probably the single most worrying feature of the Sherman was its terrifying propensity to burst into flames the moment it was hit. The Germans called the Sherman the “Tommy Cooker” while British tank crews renamed it the “Ronson” after a popular brand of cigarette lighter famed for its ability to light first time.

Two Weeks Life Expectancy

As well as the many deficiencies of British Army equipment, Render also describes the amazing comradeship, courage and ingenuity of officers and men fighting against a determined, well-armed enemy. As a junior officer, Render’s life expectancy was just two weeks once he went into the line. Over a year of almost constant action, Render would find that his mental and physical reserves quickly eroded. He freely admits that fear threatened to overwhelm him every time he was ordered to climb back into his Sherman and continue the advance.

War without End

The Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry had seen extensive action in North Africa (1940-1943) prior to David Render joining them. Once in Normandy, he noticed that prolonged exposure to combat had made many of the desert veterans excessively cautious and unreliable. On the job training was the order of the day. He would have to learn his craft from bitter, hard won experience as he and his crew fought across Normandy, Belgium, Holland and into Germany. By war’s end, the Sherwood Rangers would have earned 30 battle honours, 78 gallantry awards at the cost of 827 casualties killed, wounded and missing. However, for many of the veterans the war would never be over. At aged 90, and with a successful business career behind him, David Render remains haunted by the loss of many comrades, and one in particular. His great friend, Harry Heenan, killed in a freak accident just after saving David’s life during an engagement with a concealed 88mm anti-tank gun.

David Render’s book is a very personal, first-hand account of the tank war in Northwest Europe. In Render’s world, soldiers seldom knew what was happening in the next field or hedgerow. They knew nothing of the strategic decisions being made by Allied high commanders like Eisenhower, Montgomery or General Brian Horrocks. Instead, they focused on keeping their tanks ready for the next day’s action. They worried about being caught in a burning tank as it “brewed up”. They foraged for extra food to supplement their meagre rations. They struggled against fatigue, fear, and the terrible odds against any of them making it through alive. Sadly, David Render recently died aged 92.

The German War: Crimes and Persecution Complex

The German War by Nicholas Stargardt and The Bitter Taste of Victory by Lara Feigel are two WW2 history books that neatly dovetail one another. The German War examines the many, varied aspects of the German war experience from 1939 to 1945 at home and on the frontlines. The Bitter Taste of Victory begins in 1944 as Allied forces, East and West, advance into the shrinking Reich and extends to 1949.

The German War by Nicholas Stargardt and The Bitter Taste of Victory by Lara Feigel are two history books that neatly dovetail with one another. The German War examines the many, varied aspects of the German war experience from 1939 to 1945 at home and on the frontlines. The Bitter Taste of Victory begins in 1944 as Allied forces, East and West, advance into the shrinking Reich and extends to 1949. Both books focus heavily on the question of German guilt for the many crimes committed under the Nazi regime, remorse and reconstruction. Chillingly, each book comes to the same conclusion: the only thing the surviving Germans truly felt guilty about was losing the war. The only pity most Germans felt was self-pity. Her cities, centres of industry and infrastructure lay in ruins. Millions were displaced and homeless. Hunger, disease, and lack of winter fuel all contributed to the misery after the nation’s collapse. However, for the victims of the camps, the millions of slave labourers, and all those countries ravaged by the German war machine there was no thought, no compassion and no sense of national guilt or shame. On the contrary, population surveys taken 5 and 10 years after the war revealed German sentiment towards the Jews and many Nazi policies had barely changed for many.

The German War examines the many motivating factors that kept the German people fighting right until the bitter end, even when defeat was assured. It reveals how most Germans initially believed they were fighting a war of national defence against Poland, France and Great Britain. Later, the Allied air offensive convinced many Germans of their victimhood, although some saw it as a punishment for their crimes against the Jews. The book also exposes the lie that most Germans were ignorant of the many atrocities committed by the regime. In fact, right from the start of the conflict German soldiers were documenting their crimes in writing, photography and film. But perhaps one of the darkest aspects of the book is just how quickly ordinary men and women could be transformed from law-abiding citizens to brutal murderers and rapists. The transformation often took less than two months. In Russia, senior field commanders began to worry about their troop’s propensity to loot property, burn villages and slaughter the inhabitants without orders. When defeat and occupation finally came to the German nation it did nothing to change outlooks and attitudes. Even years after the war’s end, the majority of Germans believed that Nazism had essentially been a good idea, poorly executed.

Lara Feigel’s book The Bitter Taste of Victory begins in the closing months of the war, as reporters, writers, filmmakers and entertainers followed the advancing Allied armies into the heart of Nazi Germany. The book illustrates the utter destruction wrought on German cities by the Allied bombing campaign and contrasts it with the horrors of death and concentration camps such as Bergen-Belsen. Martha Gellhorn, Marlene Dietrich, Billy Wilder and George Orwell are just some of the famous names we encounter amidst the rubble and misery of Germany’s defeat. With incredible naivety, the occupying powers set about a process of denazification. Writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers were recruited to cleanse German culture of its Faustian excesses. However, German re-education, the Nuremberg Trials and occupation seem to have done nothing to change the population’s psyche. Instead, the realpolitik of the Cold War allowed former Nazis and war criminals to reinvent themselves without actually changing. Rather than accept any collective guilt, the Germans of the war period were satisfied to largely remain silent or seek refuge in empty platitudes and point the finger of blame anywhere but at themselves. There is some small irony that far-left-wing groups such as the Baader-Meinhof Gang would later regard the West German state as the continuation of fascism and imperialism by other means.

In reality, these two books arrive at the same stark conclusion, although starting from very different places. The Germans of the war years remained fixed in their beliefs that they were victims, not perpetrators. They largely believed Nazism was correct in its outlook, but poorly executed by the regime. That brutality, murder, and even genocide were justifiable in pursuit of national goals. These two books also illustrate just how quickly the most civilised and educated of people can be transformed into remorseless killers, happy to abdicate all responsibility for their crimes.

The BBC's Forgotten Wireless War

In this review, we take a look at David Boyle's book V for Victory: the Wireless Campaign that Defeated the Nazi published by The Real Press. The book briefly tells the tale of an almost forgotten piece of World War Two history. Enthusiastically adopted by foreign governments in exile and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the V for Victory campaign called for small acts of disobedience and sabotage by the people of Nazi-occupied Europe.

V for Victory: the Wireless Campaign that Defeated the Nazis by David Boyle briefly tells the tale of an almost forgotten piece of World War Two history. In the dark days of 1941 journalists, Noel Newsome and Douglas Ritchie took up “the weapons of responsible journalism and the instruments of the clever advertiser” to promote British ideals and explain the nation’s war aims to the peoples of occupied Europe. Together they forged the BBC’s European Service that proved such an effective foil to Joseph Goebbels’ black propaganda.

The Stay-at-Home Hour, New Year’s Day 1941, helped test the idea of a sustained campaign of honest or “white” propaganda and gauge how many people were listening to the BBC’s Foreign Service broadcasts. Nazi black propaganda in the sinister voice of William Joyce or Lord Haw Haw had certainly captured the imagination of British radio listeners during the early months of the war. On 6 June 1941 Douglas Ritchie in the mysterious guise of Colonel Britton launched the V Campaign on the ears of Europe. The audience included 15 million German citizens who risked imprisonment and even death if caught listening to the BBC.

The BBC European Service and V for Victory campaign upset just about everybody from the established political parties and security services to the Civil Service because it cut through bureaucracy. The European Service was enthusiastically adopted by political and military leaders of foreign governments in exile. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was quick to see the many possibilities of the V for Victory campaign, making the V-sign a popular gesture of defiance.

The V Campaign called for small acts of disobedience and sabotage by the people of Nazi-occupied Europe. As distinctive as any brand logo, the V-sign was daubed on walls and buildings across the continent. Ritchie made the opening notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony the sound of European resistance and the theme tune of his broadcasts. In one of the worst periods of all human history, the V for Victory campaign became a symbol of hope and solidarity.

Although David Boyle has produced a well-researched exposé of the V for Victory campaign, the book is very short and leaves the reader with more questions than answers. After all, the V-sign has its origins in the Hundred Year’s War and has continued in popular culture from the Vietnam War and Arab Spring to movies, graphic novels and popular TV mini-series. The book could have looked at the various resistance movements that emerged during World War Two, the work of the clandestine SOE (Special Operations Executive), the various aspects of psychological warfare or even Douglas Ritchie’s personal battle to recover from a stroke aged just 50. For me, V for Victory: the Wireless Campaign that Defeated the Nazis is a book that only tells half the story, maybe less, and leaves you wanting to know a lot more.

V for Victory by David Boyle is published by The Real Press.