The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We would like to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. And we look at the history of unique World War Two artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

HURRICANE: The poignant biography of the plane that won the war.

HURRICANE: The Plane That Won the War by Jacky Hyams tells the story of the Hawker Hurricane and the people who designed it, built it, fought in it, and maintained and repaired it. Read the full book review now.

One British aircraft of the Second World War has come to symbolize the indomitable spirit of the nation during the dark days of 1940, the Supermarine Spitfire. However, it was the Hawker Hurricane that shot down more than half of the Luftwaffe’s raiders during the Battle of Britain. In Jacky Hyams’s new book, HURRICANE: The Plane That Won the War, published by Michael O’Mara Books Limited, the bestselling author attempts to set the record straight.

HURRICANE is an account of how the aircraft was designed, built and its service history. The book is also a testament to the pilots, the Air Transport Auxiliary, the ground crews, and the many unsung heroes of the production line. The stubby Hawker Hurricane or ‘Hurri’ as it was affectionately known was the brainchild of entrepreneurial aircraft manufacturer Sir Tommy Sopwith and Chief Designer, Sir Sydney Camm. Today, Camm is largely forgotten while the name of R.J. Mitchell, the designer of the Spitfire, is familiar to many. Yet, Camm would lead the design teams of the Hawker Typhoon, Hawker Tempest, and the post-war marvel, the Hawker Siddeley Harrier ‘jump jet’.

The Hurricane was the first monoplane fighter to enter service with the RAF, although the Bristol M1 was briefly in service at the end of the First World War. Partially constructed from wood and canvas, the Hurricane was quicker and cheaper to manufacture than its more glamorous stable mate, the Spitfire. The Hurri was also a more rugged aircraft, capable of withstanding Luftwaffe punishment that the Spitfire could not. The aircraft’s simple design meant that during the critical days of the Battle of Britain, seemingly unrepairable planes were patched up and put back into service by maintenance units. By the 15th of September 1940, the Hawker Hurricane had shot down more enemy aircraft than all other types of RAF aircraft and anti-aircraft (AA) guns put together.

Using a combination of archive materials and first-hand accounts, Jacky Hyams’s book retells more than just the history of the Hawker Hurricane. It is a book about the countless human stories of quiet courage, sacrifice, hard work, and emotional strain that the factory workers, pilots, and ground crews endured throughout the Second World War. The author keeps the technical jargon and military acronyms to a minimum, and when used she provides short, concise explanations.

Over the post-war period, the Hurri has proven fertile ground for authors, historians, and aircraft enthusiasts with over a hundred books and articles published on the subject. So, it might be fair to say there isn’t too much new to say about the fighter. Nevertheless, Jacky Hyams’s book is engaging, easy to read, poignant, and informative in turn.

By the end of its operational life, the Hawker Hurricane had served in every major theatre of the Second World War and flown with numerous air forces from Australia to Yugoslavia. Around 25 different variants of the aircraft were eventually produced, from Hawker Sea Hurricane to tank-busting ground attack aircraft. Together with the countless men and women who gave themselves so tirelessly to defeat tyranny perhaps Sir Sydney Camm’s stubby little aircraft, the Hawker Hurricane, was the plane that won the war.

SAS Battle Ready by Dominic Utton – a compendium of forty Special Air Service operations

In this book review, we examine SAS Battle Ready by Dominic Utton – a compendium of forty Special Air Service operations.

SAS Battle Ready is the latest book from journalist and author Dominic Utton. The book is an anthology of forty Special Air Service (SAS) operations since the unit’s formation in 1941.

The book is divided into three sections. The first section, Forged in War, briefly explains the early history of the SAS from inception during the North Africa campaign to Operation Archway three and a half years later. The next section of the book examines the period between 1952 and 2000. During this period the SAS evolved with the changing nature of global threats from the decline of the British Empire to the rise of international terrorism and hostage-taking. During this time, SAS operations spanned Malaya, Oman, Somalia, the Iranian Embassy siege, London, and the Falklands War. Finally, the book concludes with the Regiment’s most recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan as part of the post-9/11 so-called War on Terror.

Perhaps due to his background in journalism, Dominic Utton has a talent for being able to summarise some of the world’s most complex conflicts in just a few brief sentences. In fact, he succeeds in telling the dramatic story of forty SAS operations from the early ‘shoot-and-scoot’ missions across the Libyan Desert to hunting for Scud missile launchers in Iraq with remarkable economy. The book also contains some fascinating facts, such as the SAS suffered 330 casualties during the Second World War while they manage to inflict around 31,000 losses on Axis forces. Clearly, David Stirling’s belief ‘that a few men could inflict more damage – with less risk - than in a traditional attack’ was fully proven.

Although SAS Battle Ready is a perfectly readable and informative book, I do have reservations about it. Firstly, a quick glance at the book’s bibliography reveals that no primary research was done whatsoever. If Mr. Utton did conduct his own research but simply neglected to cite his sources, then I stand corrected. Nonetheless, the book appears to be largely a compendium of other writers’ works. Because of Dominic Utton’s economy of research, SAS Battle Ready has nothing new to tell us about the SAS that hasn’t been said before. I, personally, have never attempted to conduct any research on British special forces. However, ex-SAS veterans like Rusty Firmin and Robin Horsfall are no longer hard men to find. In fact, both men have their own websites and are easily contactable via LinkedIn.

The lack of any evidence of primary research brings me to my second question, criticism, or concern about the writing of SAS Battle Ready, and that is why bother? Surely, given the right inputs an AI (artificial intelligence) application like ChatGPT or Google’s Bard could have produced something similar. Of course, the obvious, rather cynical answer to my own question as to why write yet another book about the SAS is that they’re popular and likely to sell. The ex-SAS soldier turned prolific author Steven Mitchel (pen-name Andy McNab) is a veritable one-man publishing house, turning out over 30 fiction and non-fiction titles based on his time with the Regiment.

It is difficult to give an exact number as new books about the Special Air Service are constantly being published. However, it is safe to say that hundreds of books have been written about the SAS since the end of the Second World War. Andy McNab’s Bravo Two Zero (1993) and Immediate Action (1995) have both become international bestsellers. More recent books like SAS: Rogue Heroes - The Authorised Wartime History by Ben Macintyre (2016) have been adapted for television and spawned a plethora of films, TV documentaries, reality TV shows, podcasts, and computer games. Audiences seem to have an insatiable appetite for all things SAS related. Luckily for the Ministry of Defence (MOD), the Regiment’s Winged Dagger unit insignia and famous ‘Who Dares Wins’ motto is Crown copyright protected, which hopefully contributes to our dwindling defence budget, but I digress. Military history and the media and entertainment industries have always had a symbiotic relationship, and long may it continue. However, writing books about the SAS that have nothing new to say and simply rehash other authors’ works seem a little cynical and opportunistic.

I’m sure Dominic Utton’s SAS Battle Ready will sell, and the publisher will no doubt see a return on their investment. Overall, I cannot help feeling a bit cheated by the book’s lack of effort. Perhaps, whoever plays it safe also wins.

SAS Battle Ready by Dominic Utton is published by Michael O’Mara Books Ltd., 2023.

The British Army’s Occupation of Northwest Germany after May 1945

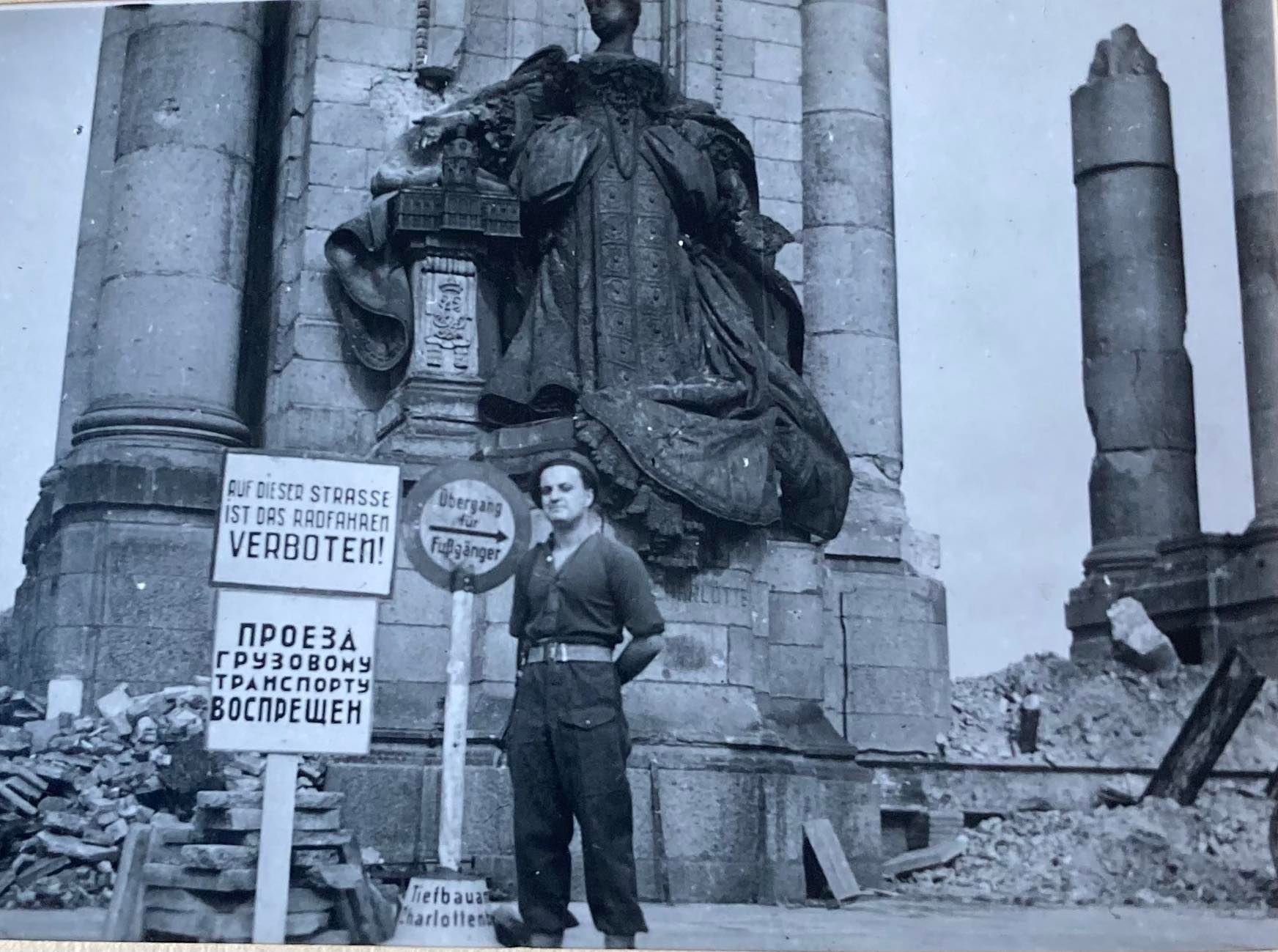

In this article, we will focus on the British occupation of Germany after May 1945, the British Army's occupation of West Berlin, the Victory Parade of July 1945, and relations with the Soviets.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945, the victorious Allied powers divided the country into four occupation zones, each controlled by one of the four occupying powers - the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. This division of Germany would mark the beginning of a new era for the country, as it faced a long and difficult process of reconstruction and democratization. In this article, we will focus on the British occupation of Germany after May 1945, the British Army's occupation of West Berlin, the Victory Parade of July 1945, and relations with the Soviets.

The British Occupation of Germany after May 1945

On 25 August 1945, Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group was renamed the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). It was responsible for the occupation and administration of the British Zone in northwest Germany, including the cities of Hamburg and Bremen, assisted by the Control Commission Germany (CCG). The CCG took over aspects of local government, policing, housing and transport.

Their primary objective was to demilitarize and disarm the defeated German forces, as well as to dismantle the Nazi regime and bring war criminals to justice. The British forces, under the command of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, faced a daunting task, as Germany was in a state of complete chaos and disarray.

One of the first challenges the British faced was dealing with the large numbers of displaced persons, refugees, and prisoners of war. The British Army, along with other Allied powers, established numerous displaced persons camps and worked to repatriate prisoners of war and refugees to their home countries. The British also faced the challenge of providing food and shelter to the German population, which was suffering from severe shortages of basic necessities such as food, fuel, and medicine. The BAOR mobilised former enemy soldiers into the German Civil Labour Organisation (GCLO), providing paid work and accommodation for over 50,000 Germans by late 1947.

The BAOR was also responsible for pursuing suspected war criminals in its zone of occupation. It established the British Army War Crimes Investigation Teams (WCIT) and was assisted by other units, including the Special Air Service (SAS). The most famous Nazi caught by the British was Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and one of the main architects of the Holocaust. He was arrested at a checkpoint and taken to an interrogation camp near Lüneburg. However, Himmler was able to escape prosecution for his crimes by committing suicide with a concealed cyanide pill. Political support for war crimes prosecutions soon declined as relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated. It soon became a political necessity for the Western powers to make friends with the Germans rather than prosecute them.

The British Sector of Berlin 1945

The British Army's occupation of the British sector of Berlin in 1945 was a key moment in the post-war history of Germany. Berlin, which was located deep within the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, was divided into four sectors, with the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain, and France each controlling a sector. The British sector was in the western part of the city.

The British Army faced numerous challenges in the occupation of Berlin. The city had been heavily bombed during the war, and many buildings were in ruins. The British Army worked to rebuild the city's infrastructure and provide basic services such as water, electricity, and sanitation.

Another major challenge faced by the British Army was dealing with the Soviet Red Army, which was stationed in and around Berlin. The relationship between the British and the Soviets was strained, with tensions running high over issues such as the repatriation of Soviet prisoners of war and the control of Berlin. The British Army, along with the other Allied powers, worked to maintain a delicate balance of power in the city, while also providing security and maintaining order.

The Victory Parade of July 1945

On 21 July 1945, the British held a victory parade through the ruins of Berlin to commemorate and celebrate the end of the Second World War. Around 10,000 troops of the British 7th Armoured Division, the famous 'Desert Rats', were paraded under review by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. On 7 September 1945, there was another parade featuring all the victorious Allies, but neither Montgomery nor U.S. General Dwight D Eisenhower attended. This gesture signified a deterioration in the relationship between the Allies, as differences in ideology between the West and the Soviet Union were becoming harder to ignore and the slide towards a Cold War had begun.

British Pathe News footage of the Berlin Victory Parade, 21 July 1945.

An Iron Curtain

Relations between the Western powers and the Soviet Union deteriorated immediately following the end of the war in Europe. The main sources of tension were the Soviet Union's unwillingness to allow democratic governments to emerge in Eastern Europe, and its desire to maintain a sphere of influence in the region. The Western powers, led by the United States, saw this as a threat to their own security and interests.

The Soviet Union's aggressive actions in the post-war period, including the establishment of communist governments in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, fuelled Western fears of Soviet expansionism. The United States responded by implementing the Truman Doctrine, which committed the U.S. to support countries threatened by communism, and by providing economic and military aid to Western Europe through the Marshall Plan.

Tensions between the West and the Soviet Union reached a boiling point in 1947 when the Soviet Union refused to participate in the Marshall Plan and instead formed its own economic bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). In 1948, the Soviet Union blockaded Berlin, prompting the Western powers to launch the Berlin Airlift to supply the city.

On March 5, 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "Iron Curtain" speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. In this speech, Churchill warned of the growing Soviet threat in Europe and called for a closer alliance between the United States and Great Britain to contain Soviet aggression. The speech marked a turning point in the post-war era and is considered a seminal moment in the Cold War.

In 1949, the three western occupation zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Soviets followed suit in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). In 1955, West Germany joined NATO and was encouraged to build a new military, the Bundeswehr. In response, the Communist states of Eastern Europe formed the Warsaw Pact.

Sources:

Photography/Images:

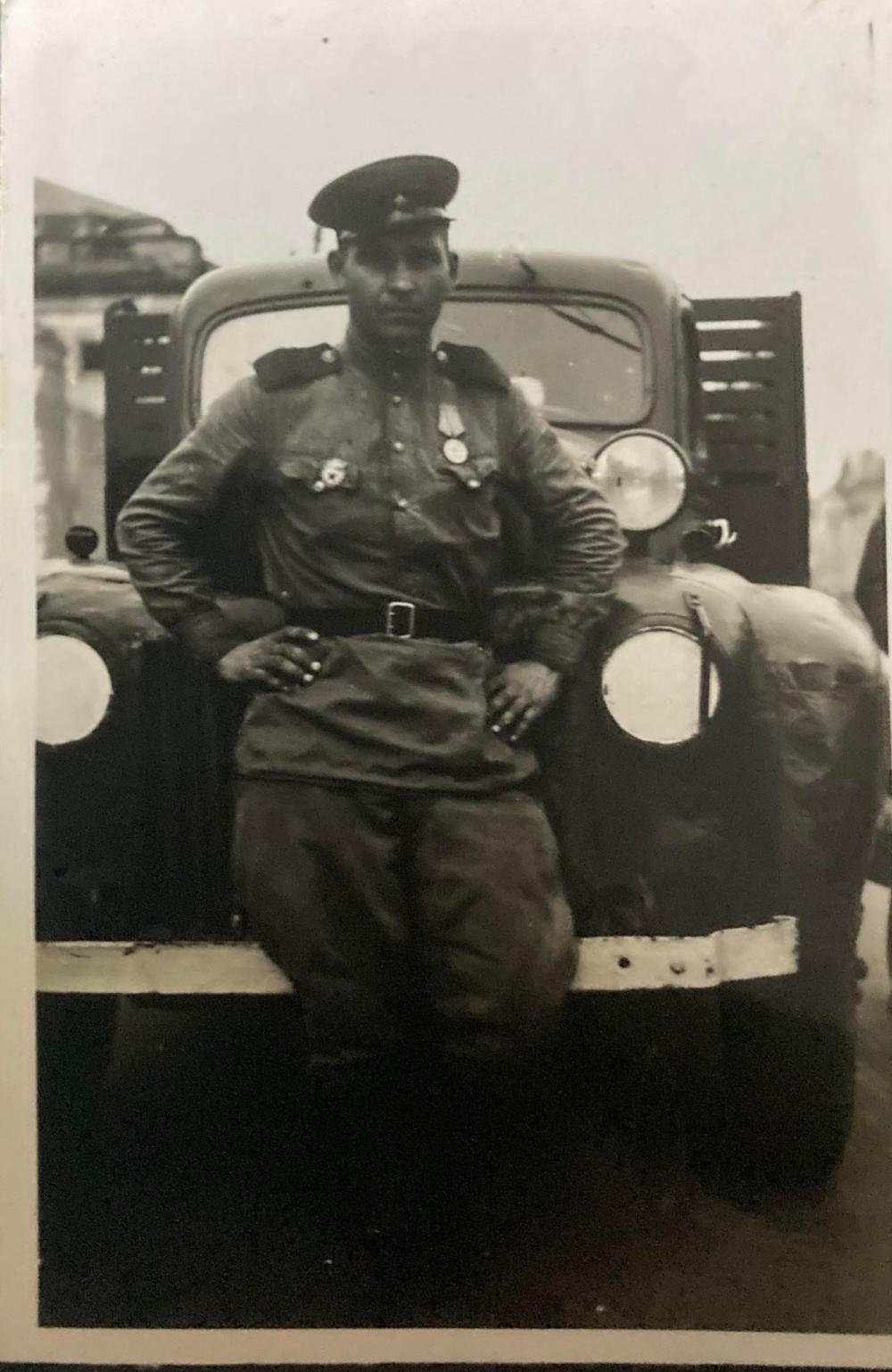

All photographs used to illustrate this article were taken by my relative George Trumpess who was stationed in Minden, Germany, and travelled regularly to Berlin during the summer of 1945.

The enduring importance of studying military history

This article explores the importance of military history and how it can shed light on the reasons behind conflicts, the motivations of those who took part, and the impact of technological innovations on warfare. It also discusses how the study of military history can broaden our understanding of the world and develop critical thinking and analytical skills.

The Second World War had a significant impact on the world we live in today. The study of military history has played a crucial role in understanding the causes and consequences of global conflict. This article explores the importance of military history and how it can shed light on the reasons behind conflicts, the motivations of those who took part, and the impact of technological innovations on warfare. It also discusses how the study of military history can broaden our understanding of the world and develop critical thinking and analytical skills.

The Second World War was a defining moment in human history, marking the end of the world as people knew it and paving the way for a new era of international relations, politics, and global economic power. It was a time of intense political, social and military upheaval, where nations and ideologies collided in a struggle for dominance and survival. Today, many years since the end of the war, the study of military history remains an important discipline, one that provides valuable insights into the causes and consequences of global conflict.

Lessons learned from a world at war

There are several reasons why the study of military history is important. First, military history helps to shed light on the reasons behind conflicts and the motivations of those who took part in them. This understanding can help to prevent similar conflicts from occurring in the future. For example, the lessons learned from the Second World War have helped to shape the modern world, including the establishment of the United Nations, the creation of international human rights laws and the promotion of democracy and free trade. However, on the first anniversary of the war in Ukraine, it is also tragically clear that the lessons of history do not prevent old enmities and new conflicts from happening.

Of course, military history can only teach us what we are willing to learn and does have practical applications that are relevant to the modern world. For instance, military history is used by policymakers, military planners and international organisations to inform their decisions and shape their strategies. Understanding the lessons of past conflicts can help to inform present and future military operations, improving the effectiveness of military interventions and reducing the risk of unintended consequences.

Technology and innovation

The study of military history can also provide insights into technological developments and innovations that have had an impact on warfare. For example, the Second World War saw the development of new weapons, tactics and technologies that changed the face of warfare forever. By studying the development and application of these technologies, military historians can help to inform future innovations and ensure that new technologies are used in the most effective and responsible manner possible.

The Second World War saw the development of many technologies that went on to transform post-war life.

The development of cryptography during the Second World War led to the creation of the first computers, which were used to decode enemy messages. The first electronic computers, such as the American ENIAC and British Colossus, were developed during the war and laid the foundation for the digital revolution that would transform post-war life. The use of computers in business, research, and everyday life has become ubiquitous, and the ability to process and store vast amounts of data has revolutionised every field of human endeavour.

Similarly, the development of jet engines during the war helped transform aviation. In 1949, the de Havilland DH.106 Comet became the world’s first commercial passenger jet. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the commercial airline industry reached 38.9 million flights globally in 2019.1 The jet engine made air travel faster, more comfortable, and more accessible to the public. But emissions from aviation have also made a significant contribution to air pollution and possibly climate change.

The jet engine also had a profound impact on post-war military aviation, enabling supersonic flight and the development of fighter jets with unprecedented speed, stealth, agility and firepower. The impact of the jet engine on travel, commerce, and military power is still felt today. For example, it is believed that the use of western warplanes like the F-16 and Gripen fighter by the Ukrainian Air Force could prove decisive in the war against Russia. Of course, only time will tell.

Critical thinking and analytical skills

In addition to its practical applications, military history is also important in a more general sense, as it helps to broaden our understanding of the world. The study of military history provides a context for understanding the complex relationships between nations, and the motivations behind political, economic and military actions. This understanding can help to inform our understanding of the world today and the events that shape it.

Furthermore, military history is an important tool for teaching critical thinking, analytical skills and historical awareness. By studying military history, students can learn how to evaluate evidence, think critically about historical events, and understand the context in which they occurred. This knowledge can help to develop the skills necessary for a successful future, whether in the military, government, private sector, or academia.

In his 1961 paper, The Use and Abuse of Military History Michael Howard discusses the role of military history in the study of war and its use and abuse by politicians, military leaders, and the public.

Howard argues that military history is an essential tool for understanding the nature of war, but it is often misused for propaganda purposes. Military history should be studied objectively, without political bias, and used to inform policy decisions. However, politicians and military leaders often use selective historical examples to justify their actions, leading to a distorted understanding of history and potentially dangerous policies.

One of the key conclusions of the paper is that military history should be used to illuminate the realities of war, rather than to glorify it or justify particular policies. Howard emphasizes the importance of studying the social, economic, and political context of war, as well as military tactics and strategy. He argues that a more nuanced understanding of history can help prevent the mistakes of the past from being repeated in the present.

Overall, Howard's paper is a call for a more critical approach to the use of military history, both in academia and in the public sphere. It highlights the potential benefits and pitfalls of using history to inform policy decisions and stresses the importance of a clear-eyed understanding of the complexities of war.2

Certainly, I would agree with Howard’s premise that military history should be studied in breadth, depth and within the context of the times to try and gain an unbiased perspective of events. To the school pupil and casual observer, history might appear dusty, static and linear, but that is seldom the case. The study of history is a dynamic, interpretive, and iterative process that welcomes new viewpoints and encourages debate.

The utility of history as a military training aid

Operation Goodwood was a British offensive launched on July 18, 1944, during the Normandy Campaign. The operation involved a massive armoured and infantry assault against German forces in the Caen sector, with the aim of drawing German forces away from the American offensive, Operation Cobra, further west. The operation was supported by a massive aerial bombardment.

Despite the numerical superiority of the Allied forces, the operation met with mixed success. The British armoured units suffered heavy losses from German anti-tank guns, self-propelled (SP) guns and tanks, while the infantry made only limited gains. Nevertheless, the operation resulted in the destruction of many German tanks and artillery pieces but at a high cost in terms of Allied casualties. Immediately after the conclusion of Goodwood on 20 July 1944, controversy began about the operational intentions of the plan.

Today, Operation Goodwood continues to generate historical debate and controversy regarding its intentions and results. Subsequently, it has become a popular subject for writers, journalists, historians, and military theorists. In 1980, General Sir William Scotter proposed that German defensive tactics used at Goodwood might provide a template for NATO forces to repel a Soviet armoured offensive in northwest Europe. General Scotter’s proposition suggested that the German defensive strategy during Operation Goodwood, which involved using a combination of anti-tank guns, minefields, and concealed infantry positions to halt enemy armour, could be effective against Soviet tank formations. The idea was that NATO forces, like the Germans, could use a combination of conventional and unconventional tactics to slow down and disrupt Soviet tank offensives. This strategy was seen as especially useful for defending key chokepoints and urban areas.3

In 1982, Charles Dick sought to refute the so-called ‘Goodwood concept.’ Dick argued against this proposition, pointing out that the Soviet army had evolved since the Second World War and had developed new tactics and weapons systems. He argued that a strategy based solely on the German model would be insufficient to defeat a modern Soviet army. Moreover, it can be argued that the German defensive strategy was ultimately unsuccessful during Operation Goodwood. After all, the Allies were still able to achieve limited success and write down tanks, troops, and equipment that the Germans could not afford to lose or easily replace. Nevertheless, a generation of British Army officers visited the Goodwood battlefield, escorted by key protagonists such as Major-General Roberts, commander of the 11th Armoured Division, and Colonel Han Von Luck, 21st Panzer Division, and quite possibly learned the wrong lessons from a study of the operation.4

According to the U.S. Army’s Centre of Military History, staff rides (a combination of battlefield tours and exercises) represent a unique and persuasive method of conveying the lessons of the past to the present-day Army leadership for current application. Properly conducted, these exercises bring to life, on the very terrain where historic encounters took place, examples, applicable today as in the past, of leadership, tactics and strategy, communications, use of terrain, and, above all, the psychology of men in battle. It is true that staff rides are widely used by military organisations across the globe as a teaching aid, but not universally.5

The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) reject the type of learning-from-history model typified by the staff ride. The IDF prefers to rely on practice and its own experience to prepare for future operations rather than the study of history. In The Staff Ride: A Sceptical Assessment, Anthony King argues that staff rides are of limited practical utility for preparing military leaders to face the unique challenges and stresses of combat. Instead, he contends that staff rides are primarily a social networking exercise, which helps unify the officer corps and create personal bonds between them. Secondly, he believes that staff rides also help fortify commanders when faced with making difficult decisions, knowing that their predecessors experienced similar challenges.6

As every conflict is a unique, never to be repeated event, the staff ride might be of limited practical use to the fledgling military commander. Nevertheless, the study of military history highlights the many similarities as well as the differences between conflicts, which in turn can provide useful templates to help inform and fortify the decision-making of tomorrow’s commanders. The British Army believes that military history can provide examples of courage, leadership and resilience that can be applied in a variety of contexts. However, it is also clear that we should be critical of how we choose to interpret historical events and the lessons we believe they teach us.

A deeper understanding of identity

The study of military history can help individuals develop a deeper understanding of their nation's identity and place in the world. In the United Kingdom, for example, military history is seen as an important part of national identity and heritage. According to The Royal British Legion studying military history can help individuals understand the significance of the role the Armed Forces have played in shaping the nation.

Military history also helps to preserve the memory of those who served and died in wars. The Second World War was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history, with millions of lives lost. By studying its history, we can honour the sacrifices of those who fought and died and ensure that their memory is not forgotten.

Studying genealogy, which is the study of family ancestry and lineage, can help someone gain a greater sense of identity by providing them with a deeper understanding of their family history and cultural heritage. Learning about one's ancestors, traditions, values, and experiences, can help individuals connect with their roots and develop a sense of belonging to a larger family community. By exploring their family history, individuals may discover inspiring stories of military service, resilience, determination, and triumph over adversity, which can serve as a source of inspiration and motivation. Overall, studying genealogy can help individuals better understand and appreciate their identity and place in the world.

In conclusion, the study of military history remains an important discipline that has both practical and academic applications. By studying military history, we can learn the lessons of past conflicts, inform future military operations and shape our understanding of the world. Whether we are students, policymakers, military planners or simply interested citizens, the study of military history provides us with a valuable tool for understanding the world and ensuring a safer, more peaceful future.

The study of military history can also teach us to be more critical and analytical and question our assumptions and biases because it provides us with a unique perspective on the past and the present. By examining historical events and military strategies, we can gain a deeper understanding of how decisions were made, what factors influenced them, and what the consequences were. This can help us develop critical thinking skills, as we learn to evaluate evidence, weigh different perspectives, and analyse complex situations.

Furthermore, studying military history can expose us to a range of different cultural and political perspectives, allowing us to see how biases and assumptions can impact decision-making. By understanding the context and motivations behind historical events, we can develop a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the world and our place in it. This can help us become more empathetic and open-minded, as we learn to appreciate different viewpoints and challenge our own assumptions and biases.

Overall, the study of military history can help us become more critical and analytical thinkers, better equipped to navigate the complexities of the modern world and make informed decisions based on a deeper understanding of the past.

Sources:

1. Number of flights performed by the global airline industry from 2004 to 2022 (2023), Statista.com, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/564769/airline-industry-number-of-flights/> [accessed 20 February 2023].

2. Michael Howard, ‘The Use and Abuse of Military History,’ Parameters 11, no. 1 (1981), doi:10.55540/0031-1723.1251.

3. General Sir William Scotter, ‘A Role for Non-Mechanised Infantry’, The RUSI Journal, 125.4 (1980), 59–62.

4. Charles J Dick, ‘The Goodwood Concept - Situating the Appreciation’, The RUSI Journal, 127.1 (1982), 22–28.

5. CMH Staff Rides, U.S. Army Center of Military History, <https://history.army.mil/staffRides/index.html> [accessed 28 February 2023].

6. Anthony King, ‘The Staff Ride: A Sceptical Assessment’, ARES& ATHENA Applied History 14, Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research (CHACR), (2019), 18-21.

4 Reasons to Research Your Ancestor's Military Service History

In this blog post, we'll explore why researching an ancestor's military service history can be of great benefit to individuals and families.

Genealogy, or the study of family history and ancestry, has become increasingly popular in recent years. It allows individuals to discover their roots, learn about their ancestors' lives, and connect with their heritage. One aspect of genealogy that can be particularly fascinating is researching an ancestor's military service history.

In this blog post, we'll explore why researching an ancestor's military service history can be of great benefit to individuals and families.

1. Gaining a deeper understanding of your family history

One of the main benefits of researching an ancestor's military service history is that it allows individuals to gain a deeper understanding of their family history. Military service records can provide details on an ancestor's rank, service dates, and where they served. This information can help individuals develop a clearer picture of their ancestor's life and experiences. For example, The National Archives provides access to military service records for British Army soldiers who served between 1914 and 1920. By examining these records, individuals can discover where their ancestors served, what battles they may have fought in, and even details about their injuries or medals awarded.

2. Connecting with national heritage

Researching an ancestor's military service history can also help individuals connect with their national heritage. In the UK, military service has played a significant role in shaping the country's history and identity. By researching an ancestor's military service, individuals can gain a better understanding of the contributions made by their family members to the country's military efforts. This can help individuals develop a stronger sense of connection to their country and its history. For example, the Imperial War Museum (IWM) in London has a collection of over 1 million items that tell the story of modern war and conflict, from personal accounts of soldiers who served in the British Army to numerous films, photographs, and publications. These documents can provide a first-hand look at what life was like for soldiers on the front lines, and help individuals connect with their ancestor's experiences.

3. Discovering previously unknown information

Researching an ancestor's military service history can also uncover previously unknown information about their life and experiences. Military service records may provide details about an ancestor's family, occupation, and other aspects of their life that were not previously known. For example, The National Archives notes that military service records can include details about an individual's next of kin, address, and occupation before and after their military service. By discovering this information, individuals can develop a more complete picture of their ancestor's life.

4. Honouring an ancestor's military service

Researching an ancestor's military service history can also be a way to honour their service and sacrifice. By uncovering the details of an ancestor's military service, individuals can gain a deeper appreciation for the challenges they faced and the contributions they made. This can be especially meaningful for individuals whose ancestors were killed in action or suffered injuries during their service. For example, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) maintains records of individuals who died in military service during both World Wars. By researching these records, individuals can pay tribute to their ancestors who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

In conclusion, researching an ancestor's military service history can be a valuable and rewarding aspect of genealogy. By gaining a deeper understanding of family history, connecting with national heritage, discovering previously unknown information, and honouring an ancestor's service, individuals can develop a stronger sense of connection to their past and their family's contributions to history. The UK is home to a wealth of resources for researching military service history, including the National Archives, the Imperial War Museum, and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. By utilizing these resources, individuals can unlock the fascinating and often poignant stories of their ancestors' military service.

If you want to know more about your ancestors' military service, please contact me today.

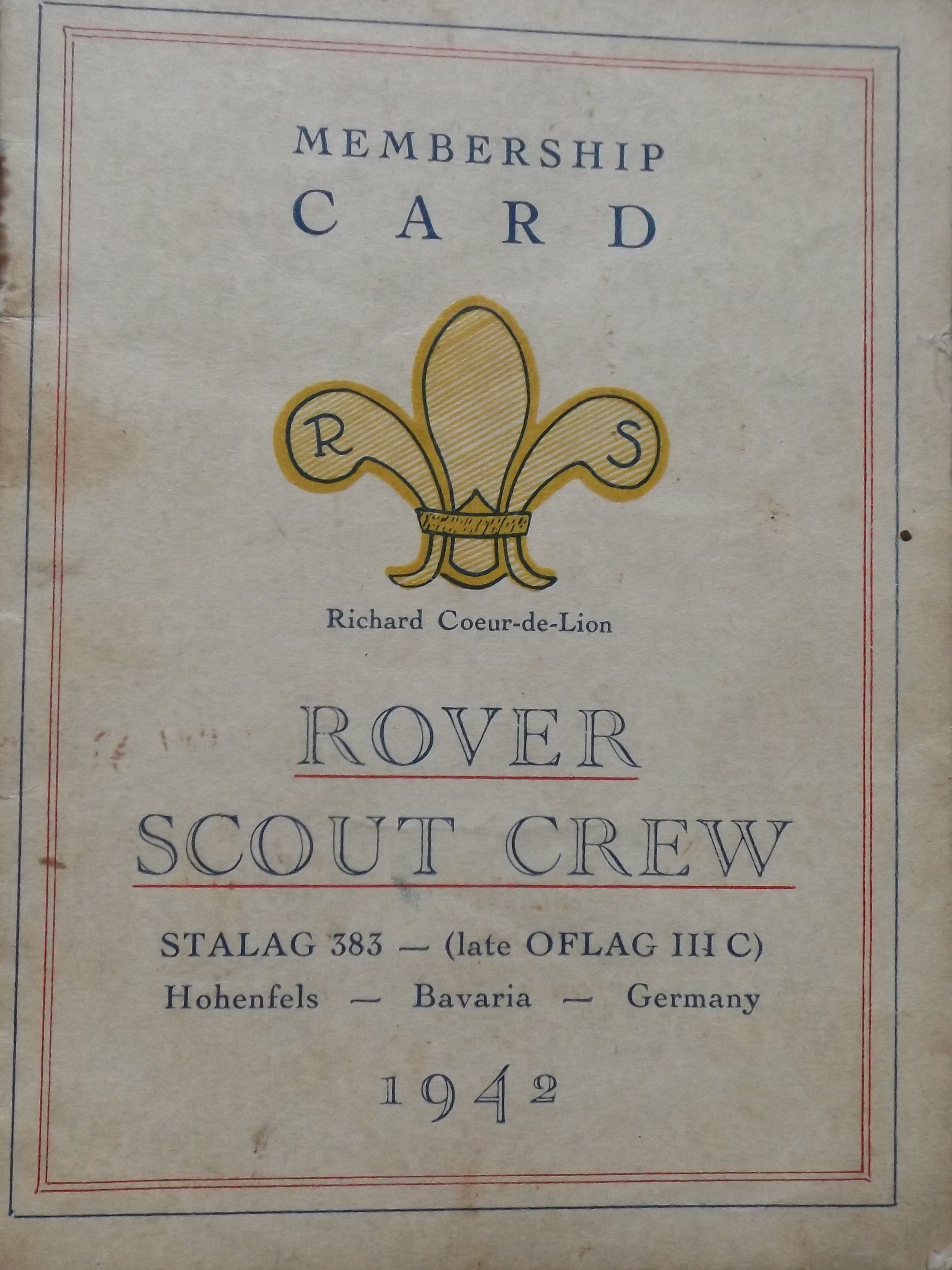

John Thorne, British Prisoner of War: Escape, Camp Life and Liberation

Cpl. John Thorne joined the Territorial Army in 1939. By 27 May 1940, John was a prisoner of war (PoW) and headed for a series of camps in Poland and Germany. John would escape, only to be recaptured. Eventually, John was sent to Stalag 383 where he would remain until April 1945. This is his story.

John Thorne joined the Territorial Army in 1939. By 27 May 1940, John was a prisoner of war and headed for a series of camps in Poland and Germany. John would escape, only to be recaptured. Eventually, John was sent to Stalag 383 where he would remain until April 1945. A member of the Scout Movement in civilian life, John was a founding member of the camp’s Richard Coeur-de-Lion, Rover Scout Crew. When the camp was evacuated by the Germans in April 1945, John and some of his comrades escaped once again. However, John’s bid for freedom and journey home did not pass without incident. This is his story.

John in uniform, probably taken in 1939 or 1940 before his deployment with the 5th Buffs to France.

April 1939

John joined the Territorial Army (TA), the 4th/5th Battalion, Royal East Kent Regiment (the Buffs). The 5th Battalion was reformed in 1939 as a 2nd Line duplicate of the 4th Battalion when the Territorial Army was doubled in size. Initially, the 5th Buffs was assigned to the 37th Infantry Brigade, part of the 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division, which was a 2nd Line duplicate of the 44th (Home Counties) Division. However, on 26 October 1939, it was transferred to the Division's 36th Infantry Brigade in exchange for the 2/6th East Surreys.

The 5th Buffs, along with the 6th and 7th Royal West Kents, remained in the 36th Brigade for the rest of the war. The battalion served with the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) in France in 1940 and fought in the Battle of France and was evacuated at Dunkirk. The 12th Division suffered heavy casualties. Unfortunately, many of the men had only very basic training before embarkation. The Division also received minimal artillery support.1

July 1939

John was promoted to full Corporal at Wannock Camp near Eastbourne.

August 1939

John’s unit was mobilised, and he was officially ‘called up’ for active service.

September 1939

The Second World War starts. John is assigned to guard Dover Priory Station and railway tunnels.

October 1939

John is promoted to acting Lance-Sergeant, Dover Priory Station, second in command (2IC) of the guard.

November 1939

John is sent on a course to the brigade tactical school (junior commanders). He reverts to the rank of Corporal. He passed the course and was recommended for a commission and then re-joined his battalion at Canterbury.

January 1940

John is sent on gas and passive air defence (camouflage and concealment) courses. Again, he is recommended for a commission.

14 April 1940

The brigade is sent to France as part of British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

May 1940

John’s unit was based at Fleury-sur-Andelle near Rouen, Normandy. He gave lectures to troops on gas and passive air defence. He was informed by his battalion commander that he would be sent home to start officer training. He was supposed to report to Aldershot on 6 June 1940.

10 May 1940

Germany invades Holland. John’s battalion is moved to Doullens, a major road intersection between Abbeville and Arras and Amiens and Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise, making it strategically important. The battalion was based at a Catholic Seminary (boy’s school) and tasked with placing roadblocks across bridges.

20 May 1940

The 5th Buffs covered a frontage of approximately 6.5 miles with three companies forward, from Pommera on the right to La Herliere. The 6th Royal West Kent, on their right, covered the approaches to Doullens. Probably the first sign of impending trouble was a wave of retreating French soldiers who passed through the line held by the Buffs. Next, the 6th Royal West Kent positioned were shelled and machine-gunned. By 12.30hrs German tank and infantry attacks were coming in along the British extended defensive line.

At about 13.00hrs the 5th Buffs were ordered to withdraw. However, it appears that this order never reached the forward companies. According to John’s written testimony, his battalion was attacked and quickly overrun by what he believed to be units of the 6th Panzer Division. According to Gregory Blaxland, the 6th Panzer Division hit the 6th Royal West Kent at Doullens while the 8th Panzer Division struck the 5th Buffs and 70th Brigade. The speed and tempo of the German advance simply could not be matched by the French and British response.

The 5th Buffs 6.5-mile defensive line, Doullens, on N25 main road, Northern France, map not to scale.

Those men who avoided immediate capture by the Germans hid in a cabbage field near a train station, and then started marching south towards Amiens. The remnants of the 5th Buffs and 6th Royal West Kent fell back on the Somme in small groups.2

During the brief fighting at La Herliere, Arras Railhead, John mentioned the brave and defiant actions of Private John Arthur Lungley (Service Number: 6584460), B Company, 5th Battalion, The Buffs. Lungley refused to surrender and kept firing his Bren light machine gun until the Germans brought up a tank to deal with him. Lungley is buried in La Herliere Communal Cemetery, France.3

Initially, Lungley was buried in the hole from which he fought. The French villagers, in defiance of the Germans, would lay fresh flowers on his grave every night. When the villagers decided to rebury Lungley in the local cemetery, the event caused such unrest, the Germans stopped the ceremony. Instead, he was quietly reburied at night but the villagers never forgot his stubborn defiance or his sacrifice.4

John’s personal notes, Monday 20 May 1940

We moved out of the seminary in Doullens just after dawn and were taken by company trucks to Le Brey Saute. The company commander, Captain Hart and his second in command (2IC) Captain Rawlins gathered the NCOs (Non-Commissioned Officers) and took us forward to inspect the ground ahead for good concealment and arcs of fire. Dispositions having been decided, the company moved forward by platoons and sections and settled into their positions by 09.30hrs.

Officially we had been told that a few AFVs (armoured fighting vehicles) had broken through on our front. In fact, it was the spearhead of 6th Panzer Division. The enemy column advanced up the road toward B Company at around lunchtime, when many of the men were in the rear area visiting the ration truck.

The platoon .55 calibre Boyes anti-tank rifle was manned by No. 1 Section, who opened fire. This gunfire stopped the enemy lead vehicles. After just three rounds had been fired the order was given by B Company commander for all those manning Brens (Bren light machine gun) and ATRs (anti-tank rifles) to retire to the nearby train station, where trucks were waiting to evacuate us.

On arrival at the train station, the Germans brought a heavy machine gun into play, sweeping the station forecourt, where our trucks were situated. Captains Hart and Rawlins were trying to organise a defense of the station. Under heavy fire, I received permission to get boxes of ammunition off the trucks. Shortly after returning to the company, Captain Hart gave the order, ‘Every man for himself.’ At this point it became obvious many of us would become prisoners of war (PoWs). I decided to try and get away and contact one of the other companies. I managed to get through a barbed-wire fence and across a railway embankment without being spotted by the Germans.

Crawling into a cabbage field, John came across Captains Hart and Rawlins and several NCOs from the company who had also evaded capture. They watched while the Germans used the company’s own trucks as prisoner transport. The group of escapees moved west until they came across a road filled with a constant flow of German vehicles. Hidden at the roadside, the group waited about an hour for a break in the traffic and eventually decided to change direction and move south and try to reach the Maginot Line.

Tuesday 21 May 1940

John’s group of fourteen men moved south across-country. They were provisioned by the generosity of local French inhabitants. Captain Hart was able to draw up a route of march for the group by copying a map provided by a French villager. The group observed endless columns of German vehicles on all the major roads. Captain Hart’s route would take them south and then southwest to Les Andelys.

Wednesday 22 May 1940

On leaving the village where they had received help, the group moved cross-country once again, avoiding main roads. They crossed a field crisscrossed with tank tracks and discovered the bodies of several dead French soldiers laying in a ditch.

Saturday 25 May 1940

The men became separated into two groups while crossing a road during a brief gap in the German traffic. The two groups were never reunited.

Sunday 26 May 1940

John’s group moved toward the river Somme. German artillery had the far bank of the river under fire with shells passing over the heads of the men.

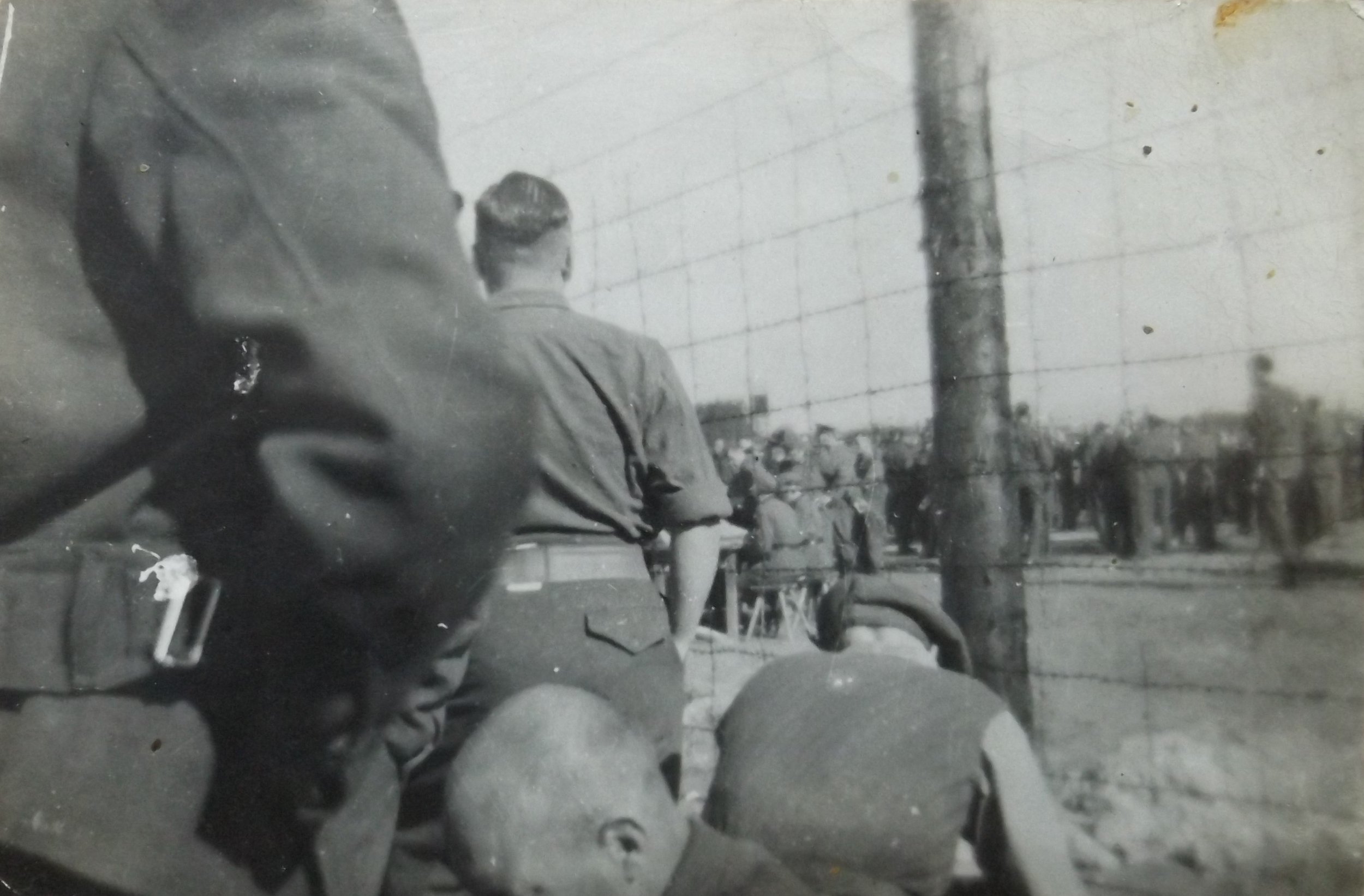

Monday 27 May 1940

John’s group decided to try and cross the river to reach the Allied side. However, the group were surprised by a German sentry and taken prisoner. The group was transported to the German company headquarters, where they gave their names, ranks and serial numbers. Captain Hart was separated from the other ranks. The group was moved by truck to Albert. Next, they were taken to a French aircraft factory and put under guard outside one of the hangers. John recalled how the group of British prisoners became an object of curiosity to passing German troops.

In general, the Germans were either friendly or indifferent to the British servicemen. One German soldier (sometimes referred to as a Landser) stopped to chat with the group in English, and even shared his rations with them. At around 14.00hrs the group was transported toward Bapaume. At about 17.30hrs the group was moved by lorry to Cambrai, where they spent the night at a barracks, sleeping outside on the parade square.

Map of the Principle British and Dominion prisoner of war camps in Europe, 1944,

British Red Cross, Museum & Archives.

Tuesday 28 May 1940

John’s group were taken to Charleville on the river Meuse. Later, they were driven to Bitburg, north of Trier, where they were forced to camp in the open for five days.

Monday 3 June 1940

The prisoners were taken to a railway siding and loaded onto cattle trucks. John was appointed the NCO in charge of his truck, which was overcrowded with around 70 men. John believed the cattle trucks should have accommodated no more than 40 men. From Bitburg the train took them northeast to Koblenz, north to Bonn, Cologne, Dusseldorf, Duisburg, Essen, east to Kassel, northeast to Magdeburg, Berlin, east to Poznan, and finally northeast to Thorn (Torun), Poland. John simply described the journey as long and uncomfortable.

The prisoners were held at Stalag XX-A (Fort 12, Camp 13) until sent to work in Danzig on 25 June 1940.5

Notification that John was interned as a prisoner of war, June 1940.

25 June – 25 August 1940 – Danzig (Gdańsk)

John was rather vague in his description of the camp at Danzig. Using information on the Forces War Records website, John was probably moved to Stalag XX-B Marienburg, Danzig (now Malbork Poland). Originally built during the First World War, the camp was in a poor condition by the time British, Poles and Serbs were held there in 1940. He does say the camp was built on a hillside overlooking the harbour.6

During the second week at the camp, John became friends with Ted Lancaster, Bert Johnson (Sherwood Foresters) captured in Norway, Lance-Corporal Bill Bailey (King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry) also taken in Norway and Sergeant Bill (Darkie) Jones (Royal Signals) captured in France. Together, John and his new group of friends planned to escape from the camp.

The escape was scheduled for 25 August 1940. The men were provisioned by the camp’s escape committee. Having cut a hole in the perimeter fence, the group slipped out of the camp. The poor upkeep of the camp might have made the group’s escape easier. They climbed up a slope covered with undergrowth and emerged in what appeared to be a public park with many people enjoying a Sunday stroll. The men remained hidden in the undergrowth until dark. Ted had managed to keep a compass hidden on his person. They spent the next few days moving at night and laying up during the day.

29 August 1940

The escapees passed out of the Free State of Danzig. Next day they turned east towards the Russian frontier.

5 September 1940

The group reached the banks of the River Vistula just before midnight but it was too wide to swim across. They found a small rowing boat with just a single oar, and managed to cross the fast-flowing river, which John estimated was about a mile distance.

7 September 1940

Moving along the back of a row of houses, a German policemen apprehended the group at gunpoint. The group had allowed themselves to be seen by several civilians during the previous days. Additionally, just before their capture, two of the group had stopped to ask a resident of the village for cigarettes. The men might not have realised it at the time but around 95 percent of the population of the Free State of Danzig were German, not Polish, and so likely to inform the authorities about them.

On re-capture, the group was transported by truck to a German military prison before being sent back to Danzig by rail. The journey took around three and a half hours by train. It had taken the men 14-days to cover the same distance on foot. To add insult to injury while at Stalag XXA, Camp 13, John and many other prisoners contracted lice.

September 1940 – April 1941 - Stalag XX-A (Thorn/Torun)

On their return to Stalag XXA, the escapees were first kept together in a cell, separated from the other prisoners, for about three weeks. As a punishment for their escape each man would be kept in isolation for 68-days. However, before the punishment was carried out, John was taken ill with suspected Diphtheria (a serious bacterial infection which can cause breathing problems, heart failure and death). He was sent to Fort 14, the camp hospital, and confined there for four weeks. On discharge from hospital, John was sent to Camp 13 where he was placed in a large barracks with hundreds of men, all sleeping in cramped three-tiered bunks.

Suddenly, without warning, John and about 100 other prisoners, all escapees, were transferred by rail and then road to Stalag XI-B Fallingbostel (work camp).

April – July 1941 - Stalag XI-B Fallingbostel (work camp)

Stalag XI-B was one of the Wehrmacht's largest prisoners of war (PoW) camps, holding up to 95,000 prisoners from various countries. In fact, the camp was a complex of small camps spread over many square miles. Stalag XI-C was part of this complex but is better known today as the infamous Bergen-Belsen. The new arrivals at the camp showered, had their heads shaved and uniforms disinfected. John wrote that the camp was clean and well kept. The British prisoners were quartered with a group of French junior officers. The two groups immediately started to plan an escape. However, John’s group were separated from the Frenchmen a few days later and assigned to work parties.

John’s work party was given the task of laying pipes for an agricultural irrigation system. Over a period of a few weeks several men took opportunities to escape. However, most of these escape attempts were spur of the moment decisions and poorly planned.

May – June 1941 – Stalag XI-B - Lüneburg Heath, north of the camp

As John’s work group received no food from their German captors, they decided to go on strike. The guards threatened to shoot the prisoners if they did not go back to work. After a tense standoff between the two groups, the prisoners finally returned to work. As a punishment for refusing to work, John’s group were confined to their quarters without food for five days. It later emerged that the reason the Germans had not fed John’s work party the day of the strike was because it was the Whitson holiday. The guards had planned to return the work party to the camp early and allow the men a half-day holiday. Instead, on release from their confinement, John’s group were immediately transferred out of the camp and sent back to Poland.

Stalag XXI-A, Schildberg, Posen

On arrival at the new camp, John found many of the prisoners were recovering from wounds and some were awaiting repatriation to their home countries. After a few weeks, John and his comrades were assigned to a work party but discovered that it was war work, which was a violation of the Geneva Convention. Naturally, the British refused to work. Once again, the group was threatened with loaded rifles by the German guards but this time they did not back down. Instead, the group was returned to the camp.

July 1942 – April 1945 – Stalag XXI-A – Oflag III-C later renamed Stalag 383, Hohenfels, Upper Bavaria.

The camp comprised 400 detached accommodation huts, each typically housing 14 men. More were built towards the end of the war as prisoners were moved in from other camps as the Russian front advanced from the east. According to John’s testimony, when the British group arrived at the camp there was around 3,000 prisoners including RAF aircrews. When the camp was evacuated in April 1945 the number of inmates had grown to around 18,000 Allied personnel including Americans, Canadians, ANZACs, South Africans, Palestinians, and men from many other commonwealth nations.

Midge Gillies described Stalag 383 as a drab, miserable shanty town designed specifically to hold Allied NCOs who refused to work. The prisoners retained a great deal of autonomy in the organisation and running of the camp. A German censor at the camp wrote that the British prisoners did not give a damn who owned the camp, they just ran it how they liked – and patronised everybody. One of the PoWs said that the guards assumed the status of attendants at a holiday camp. In truth, the prison was no holiday camp for the inmates.

Mental Stress

The mental stress of incarceration showed itself in different ways in British prisoners of war. The camp inmates of Stalag 383 occasionally went ‘Stalag happy’ and performed the most bizarre and elaborate charades to occupy and entertain one another. Strange behaviours demonstrated by groups and individual inmates included holding a full-scale fox hunt through the camp and the setting up of an imaginary railway service to England. Inmates dressed as the Emperor Napoleon, Admiral Lord Nelson, and a tribe of North American Indians. One prisoner regularly walked an imaginary dog, another herded imaginary sheep while a third rode his imaginary motorcycle around the camp.

The Commandant of Stalag 383 became so concerned with the mental health of the prisoners that he suggested to the Senior British Officer of the camp that some men could take walks under parole outside the camp to alleviate the symptoms of stress.7

Food Scarcity

In 1944, there were about 90,000 British prisoners of war held in Germany or camps in occupied territories. In contravention of the Geneva Convention, which required the Germans to feed prisoners a basic, balanced diet, the men never received proper rations from their captors. The British Red Cross, St. John War Organisation, YMCA, and International Red Cross worked tirelessly to ensure prisoners were able to receive food parcels from home. Instead of luxuries, food parcels became necessities, supplementing the prisoners’ poor, unbalanced diet. However, the Germans were meticulous in the delivery of Red Cross and similar parcels, making them a top priority for the transport system.

Over the course of the Second World War, the British Red Cross sent around twenty million food parcels from the UK to British Prisoners of War scattered around camps in Nazi-occupied Europe and in the Far East. Around 163,000 parcels were packed each week except at the start and toward the end of the war.8

As well as food, the British Red Cross and St. John War Organisation sent clothing, books, musical instruments, games, and many other sundry items to British captives. It’s clear that a certain amount of pilfering was done by the Germans, nevertheless, most items did eventually reach their intended destination. Naturally, lack of food, over-crowded accommodation, inclement weather conditions, and disease all took their toll on the prisoners’ health and mental well-being.9

Prisoner of war food parcel, 1939-1945, British Red Cross, Museum & Archives.

The Rover Scouts

On 15 September 1942 the first British NCOs arrived at Oflag III-C. The British were placed in the camp because they were unwilling to work for the Germans. On arrival at the camp prisoners tended to form into groups based on nationality, branch of service or some common interest. One of the first groups to form in the camp was of people connected with the Scout Movement in civilian life.

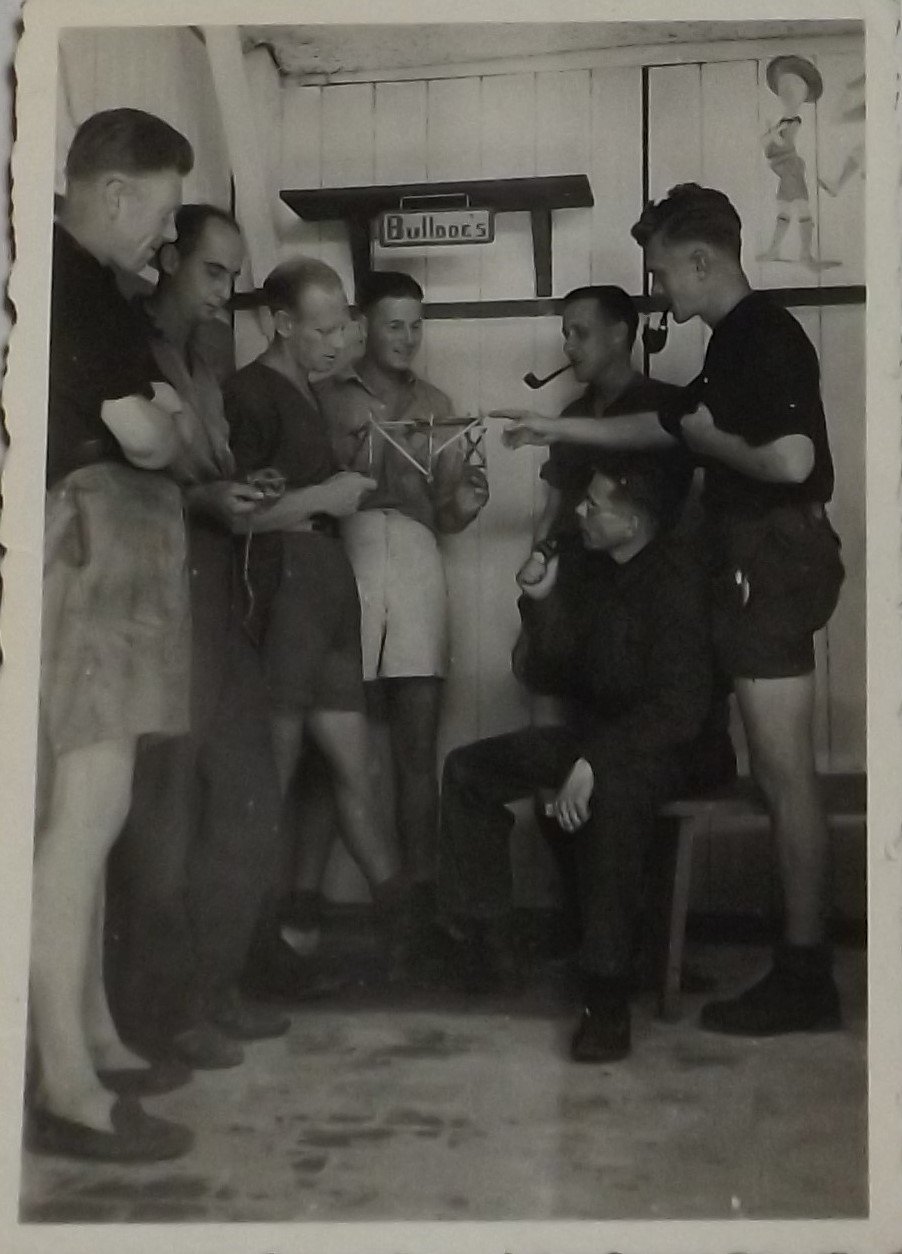

In October 1942, a group of British and commonwealth prisoners decided to form an official Rover Scout Crew, which they named Richard Coeur-de-Lion (Richard the Lion Heart). The Scout Leader was Australian warrant officer Ivan C. Stevens, better known as Steve. John was appointed Quartermaster. The crew was divided into three patrols: the Bulldogs, Nomads and Owls. An old harness room in one of the disused stable blocks became the scout Den and was later used as the camp school room and library. As suitably quiet accommodation for study was extremely limited in the camp, the Den was opened as a ‘quiet room’ for those seeking solitude. A member of the scout crew would always be in attendance when the Den was open.

The scout crew took on many of the mundane chores necessary to keep the camp functioning such as collecting firewood. The scouts organised numerous activities to keep its members and other prisoners busy from debating societies and amateur dramatics to sports and various self-improvement classes. First Aid classes were taught by the scouts until a St. John Ambulance Brigade was formed in the camp. The Brigade performed medical duties at all camp football matches and theatre performances. Members of the scout crew took an active role in the many theatrical productions held at the camp’s National Theatre. The scout crew organised social events such as the annual Christmas party. Holidays like Christmas and New Year could be particularly difficult psychologically for prisoners. Depression could settle on a man; its symptoms so well recognised the prisoners called it ‘barbed-wire disease’.10

John (marked with an X) during the Scouts last Christmas Party in Stalag 383. John in the Scout Den with some of the crew, Christmas 1944.

Click on images to enlarge

Camp Universities

Francis Newman was the first British serviceman to pass a professional examination in a prison camp during the Second World War. For many men, captivity represented an opportunity to gain an education and qualifications that would have otherwise been denied to them in ordinary life.11 Stalag 383, John said the camp contained so many talented people with nothing but time on their hands that a Warrant Officer (WO) from the Royal Army Educational Corps started a Stalag University. The University taught a wide range of subjects and attracted thousands of students.

The Educational Book Section of the British Red Cross PoW Department was responsible for collecting and dispatching books for study to men in the camps. By May 1942 the Educational Book Section had received 15,355 requests for books and study aids and had arranged for over 69,000 educational books and 3,542 study aids to be sent to the camps, regardless of a wartime shortage of paper. The British Red Cross approved 6,091 different exam papers from 136 different examining bodies from Cambridge University to the Beekeepers Association. The Red Cross also sent rulers, mathematical instruments, drawing boards and chalk. Medical students were sent skeletons and other anatomical specimens to help them pass practical biology exams. The Germans would provide tables and chairs for examination rooms. The Educational Section sent 17,000 exam papers to students who sat around 11,000 exams with an average pass rate of 78.5 percent.12

A collection of photos of a Stalag 383 ‘National Theatre’ production of Rope, winter 1944.

September 1942 – April 1945

As the inmates refused to work for the Germans, they had plenty of time to kill. Subsequently, numerous sports were played in the camp. The inmates even managed to transform a large concrete water tank known as the Fire Pool (which provided a central source of water in the event a fire broke out within the camp) into a serviceable swimming pool. John remarked how during hot days the swimming pool was often crowded with inmates until lights-out. Many aquatic sports competitions were held in the pool and each of the fourteen companies fielded a water polo team. John also helped the camp escape committee but gives no details of his activities in his testimony.

Using clandestine radios, the inmates were able to monitor news broadcasts and follow the Allies advance into Germany during the last months of the war. In early April 1945, the prisoners were informed the camp was to be evacuated.

John, standing, right, probably taken in Stalag 383 as all subjects are NCOs.

12 April 1945 – Stalag 383

John wrote that on 12 April 1945 the Red Cross white ladies (army lorries painted white and driven by British military personnel (PoWs) accompanied by German guards and a Red Cross representative) arrived at the camp. Red Cross parcels were handed out, one between four men. Next, the prisoners were moved out of the camp and onto a road. John said that whether the men were march-fit, sick, or disabled, it was all the same to the German doctors. Everyone who could be found was forcibly evacuated from the camp. Apparently, many inmates concealed themselves in various hiding places within the camp to avoid the exodus. There was no motor transport for the inmates and by nightfall men were dropping out along the line of march. At first, John explained, the guards would try to rouse the small groups and get them marching again. But later, no one from the camp administration came along when John and a small group of his comrades dropped out for a rest. They took this opportunity to slip away from the forced march.

13 April 1945

Early the next morning John and his friends cleaned themselves up and then moved off in regulation fashion. John recalled that they looked quite smart as they marched along. However, the group were stopped by a German Field Police (Feldgendarmerie) unit looking for deserters. The Feldgendarmerie turned the British over to a small group of German truck drivers who had lost their vehicles when they had been attacked by Allied fighter-bombers. Together, the little mixed group of Germans and British NCOs marched about ten miles to Hohenberg (unfortunately John is a little vague about the exact location but is probably the town between Stuttgart and Nuremberg). The British were handed over to the civil authorities in Hohenberg, where they were given rations and bedding, and remained there for a few days.

14 April 1945

John wrote that at about midday on 14 April, a French soldier called Rene joined their group. He said he had been picked up outside Regensberg, which is east of Hohenberg, after he had escaped from a PoW camp. John remarked that he seemed pleasant enough and spoke good English.

15 April 1945

John and his comrades were put to work around the town but were not closely supervised. During the afternoon of 15 April, a German military motorcycle came racing through the town pursued by an Allied rocket-firing Typhoon aircraft. To try and evade its pursuer, the motorcycle went over a humpbacked bridge at speed and then turned into a large barn that stood beside the road. At the same moment, the Typhoon pilot fired a salvo of rockets. The rider and passenger either jumped or were thrown clear as the motorcycle crashed into the barn. In the next moment, the rockets hit the barn and it exploded. Unfortunately, the barn housed cows and horses. John explained how the nearby towns people and PoWs rushed to the scene and were able to save about seven or eight of the 15 animals trapped in the inferno.

16 April 1945

The next day, after the episode with the Typhoon and motorcycle, the local Bürgermeister (mayor or chief magistrate) sent for the group of PoWs. The Bürgermeister was concerned that the town’s women would be raped when American troops arrived to occupy the town and asked the men to intercede on the town’s behalf. This fear that the town’s women would be raped was probably due to propaganda and stories of widespread rapes and killings of German civilians by Russian troops in the east of the country.

17 April 1945

John recalled that around breakfast time he heard a commotion downstairs and on investigation found Stan “NAAFI” Henson in a car with a group of chaps, all armed to the teeth, from Stalag 383. Henson informed John that the prison camp had been liberated by the Americans. The German doctor who had insisted that all the sick and disabled prisoners be evacuated from the camp had been shot dead. Henson’s group left John and his comrades with arms and ammunition and told them to roundup any German soldiers left in the town. Next, John says they went to see the Bürgermeister and told him that the town’s folk should hang white bed linen from upstairs windows and public buildings to signify surrender. The British NCOs then went around confiscating weapons from those German troops who remained in the area.

Just after lunchtime an American Jeep arrived in the town square. John and his comrades made themselves known to the American troops. The jeep was the point detail or reconnaissance vehicle for the approaching 4th Armoured Division. An American Private asked John if he would sell him the Luger pistol (P08) he was carrying. These were highly prized souvenirs amonst American troops. John said the Private was overjoyed when he simply handed the pistol over as a gift. As elements of the armoured division started to rumble through the town, John and his comrades sat beside the road while American troops tossed them cartons of cigarettes, C and K-rations as they passed.

At dusk, the group was transported by the Americans to a farmhouse some miles away. The German farmer and his family were relocated to the barn.

18 April 1945

About lunchtime John’s group moved to an American Army encampment. Next, the group moved to Nürnberg (Nuremberg) and were informed that they would be handed over to AMGOT (Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories). AMGOT wanted to move John and his comrades back toward Stalag 383. This arrangement did not suit John, who wanted to move forward, not back. So, John and Rene decided to make their own way home. First, they got a ride in an American Army truck heading northward. However, the truck dropped them in the middle of nowhere. They walked to the nearest village, which was occupied by the Americans. They were taken into custody and interrogated by an American intelligence officer. As John had letters from home and some official documents on his person that substantiated his story, he was eventually released from custody. John was sent to the guardroom where the Military Police made him welcome, but Rene was not released. The commander of the guard kept referring to John’s ‘kraut’ friend (meaning Rene).

Next morning, driving out of the village, John passed a large PoW stockade and one of the prisoners was Rene. John was told that Rene was not a Frenchman, but a German Obergefreiter from a Panzer Grenadier Regiment stationed near Regensburg. When his unit’s camp was about to be overrun by the Americans, Rene had fled and hidden in a nearby forest. Later, he had murdered a French PoW and stolen his identity. John never learned the German soldier’s real name or his fate.

19 April 1945

John was taken to a US airfield where he waited for a flight home. A group of American servicemen took him under their wing and entertained him. While at the airfield, John said he watched the film White Christmas, but he was mistaken as the movie was not released until 1954. He probably watched the film Holiday Inn (1942), which featured Bing Crosby singing the song White Christmas.

20 April 1945

After waiting around all morning on the runway, John and two British officers were told they would be put on a flight to Ghent, Belgium, but due to bad weather the flight was re-routed to Paris, France. The flight landed about 17.00hrs and they were taken to a US Rest Centre nearby.

22 April 1945

Finally, John got a ride on an RAF Transport Command, Handley Page Hampden aircraft to RAF Croydon. Next, John went to Chalfont Saint Giles and then to Worcester. Two days later, he was on a train home. When John left for France in 1940, he weighed 12 stone 8oz. On his return to England, he weighed just 8 stone 3oz, but he was home at last.

A telegram announcing John’s arrival home, which reads: ‘John Stafford arrived yesterday evening without a rag to his back or a penny in pocket. Mother naturally shocked at his appearance but getting over it. Charles.’

Primary sources

John Thorne’s family provided a range of official documents, maps, books, and photograph albums plus 50-pages of handwritten testimony about his wartime experiences and his life in various prisoner of war camps.

Secondary sources

1. Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment), see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buffs_(Royal_East_Kent_Regiment)

2. Destination Dunkirk: The Story of Gort’s Army, Gregory Blaxland, William Kimber & Co. Ltd., 1973, pp. 121-129

3. Commonwealth War Graves: https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2279541/john-arthur-lungley/

4. Destination Dunkirk, Blaxland, p. 131

5. Stalag XXA https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalag_XX-A and Torun Fortress https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toru%C5%84_Fortress

6. Stalag XX-B Marienburg, Danzig https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/european-camps-british-commonwealth-prisoners-of-war-1939-45

7. The Barbed-Wire University: The Real Lives of Allied Prisoners of War in the Second World War, Midge Gillies, Aurum Press Ltd, London, 2011, pp. 76-83

8. British Red Cross, Museum and Archive, Prisoner of War Food Parcel webpage, accessed 15 May 2022 https://museumandarchives.redcross.org.uk/objects/8944

9. Prisoner of War: The Story of British Prisoners held by the Enemy, Noel Barber, George G. Harrap & Co Ltd, London, 1944, pp. 13-17

10. Glowing Embers, R. Philip Smith, Jarrold and Sons Ltd, Norwich, 1946, pp. 7-19

11. Prisoner of War, Barber, pp. 40-49

12. The Barbed-Wire University, Gillies, pp. 271-288

Additional resources

The Red Cross Museum archive https://museumandarchives.redcross.org.uk/objects/29269

The Museum of St. John https://museumstjohn.org.uk/st-john-during-the-second-world-war/

Stalag 383 Bavaria: A History of the Camp, the Escapes and the Liberation, Stephen Wynn, Pen & Sword Military, 2021.